Audiophiles are like sommeliers of music. You need an experienced palate to know how to pick up notes of pear and oak in a fine wine just like you need an experienced ear to listen for crisp hi-hats and full-bodied reverb in a song. This became apparent when I heard about Amazon Music’s new high fidelity music streaming service. I started the free trial and expected to be blown away by the sound quality. To my dismay, I could not tell a significant difference between high resolution and the normal resolution sound quality of the streaming services I was used to.

Wondering if I was the only one, I sent an audio quality quiz to my Berklee Online coworkers, a pretty musically inclined group, if we do say so ourselves. NPR released the quiz that you see below when the lossless music streaming service, TIDAL, launched in 2015, to determine whether listeners could decipher an uncompressed WAV file, from a 320 kbps MP3, from a 128 kbps MP3. Our average score as a group of 10 was 48 percent.

If there were anyone in the world who would be able to tell a high quality recording from a low quality recording and everything between, it would be our music production instructors at Berklee Online. I spoke with four instructors to get their thoughts on high fidelity streaming, its relevance in their lives, and in the lives of average listeners.

As it turns out, Sean Slade and Prince Charles Alexander have both used the NPR quiz with their music production students and saw similar results.

“When I included [the NPR quiz] in a discussion in my online graduate class, everybody had the same reaction,” says Slade. “‘Whoa, I thought I was so cool and yet I got a lot of this wrong.’ So that taught me something.”

I spoke with Slade and Alexander, along with Erin Barra and Jonathan Wyner. Slade and Alexander both say they can hear the difference between a high fidelity recording and a non high fidelity recording, but agree that the differences are minute.

“If there’s any discernible difference, it’s so subtle and so slight, you would have to be somebody who’s been in the business for decades like me to hear it,” says Alexander, who as a recording and mixing engineer has worked with clients like Mary J. Blige, Destiny’s Child, the Notorious B.I.G., Sting, Aretha Franklin, and others. He has garnered more than 40 platinum and gold certifications from the RIAA (Recording Industry Association of America) and has multiple Grammy Awards and nominations.

To prepare for our conversation, Slade says he treated himself to a pair of top-of-the-line headphones. He gained worldwide recognition co-producing Radiohead’s first hit, “Creep,” and later the band’s debut album, Pablo Honey. Slade conducted a side-by-side analysis of TIDAL, Spotify, and Amazon HD.

“I could tell the difference, but the differences were so subtle that they might be meaningless,” he says. “TIDAL had the best soundstage and Amazon HD, which was CD quality, was a close second—I could hear it. It didn’t quite have the space in the high end that TIDAL did, but the differences were minimal. And then Spotify did sound different. It had a little bit more kind of mid-range, a little less Hi-Fi-y crystal clear high end, but it had more punch, and I thought musical life in the midrange.”

Barra and Wyner agree with their colleagues that the average listener likely cannot hear the differences in lossless audio, however, they see its value for music industry professionals and audiophiles.

“Somebody who has ears that are developed in that way, they probably can hear a big difference, and it is a meaningful difference,” says Barra. “But to most people, they’re just not able to really hear that, or they’re not even listening in that way.”

Barra, an expert in creative music technology application, says that she was raised by an audiophile. As a producer, composer, and songwriter, she has represented companies such as Ableton, ROLI, MusicTech, Moog, and iZotope. Barra can foresee the average listener caring about music playback quality, especially since people are investing in more sophisticated audio technology like Beats headphones and AirPods.

“I grew up in that energy that, ‘look, recording quality really does matter, and listening is something that should be taken seriously,’” she says. “I feel a bunch of different ways about it, but I think that having higher fidelity streaming would be awesome. And the world is changing a lot because people are caring about the type of playback scenarios that they have access to.”

Wyner says that for the vast majority of listeners and the context in which they listen to music, he doesn’t think that music streaming quality matters that much.

“That’s not to say it isn’t important,” Wyner says. “I do think it’s important and for me personally, I’m always interested in getting as much of the experience and results of the artistry as possible.”

When asked which music streaming services he subscribes to, Wyner answers, “All of them.” He streams Spotify, TIDAL, Apple Music, and the new Amazon HD. As the owner of M Works Mastering Studios in Cambridge, Massachusetts, he has mastered commercial releases by the likes of James Taylor, David Bowie, Aerosmith, Pink Floyd, Cream, and more. Wyner has recently been appointed president-elect of the Audio Engineering Society (AES).

“I think high resolution audio within reason is fantastic,” he says. “For me, would I be happy to have 96 kHz/24-bit version of everything I listen to—absolutely. Because at that point I’d have no constraint about my ability to hear all of the nuances that went into making the record.”

Wyner points out that internet bandwidth was once a barrier to high fidelity streaming, but that has changed over the past decade.

“High speed internet access meant something very different 10 years ago,” he says. “These days, at least in major metropolitan areas, people have really wide pipes. It’s actually not that hard to serve people lossless audio or pretty darn close to lossless audio. Once the technical restraint goes away, we can give people really high quality audio. So why the heck don’t we?”

TAKE A MUSIC PRODUCTION COURSE WITH BERKLEE

Alexander foresees technical restraints to high fidelity streaming, including internet bandwidth and redistribution issues.

“We are in a generation where there have been many higher res things that have already been sampled down to MP3s, and then the MP3 is now up-sampled to high res,” he says. “So, am I really listening to a high res file? No. So even discerning where the original music came from would be a journey; to go to the original record company, find the original master, get it printed in some high res format. And then upload to some streaming site . . . That’s just a lot of work. Who wants to do that?”

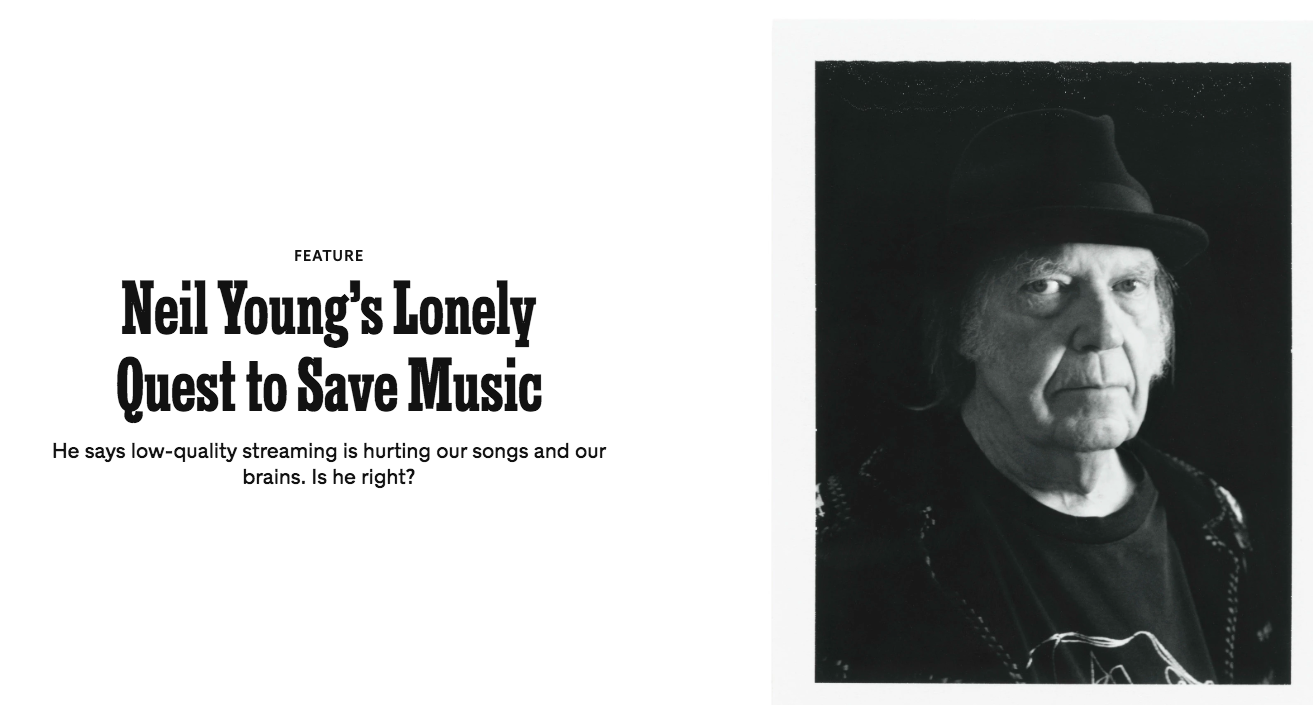

Currently leading the dialogue about the importance of music quality and playback is Neil Young. Over the past decade, he has fought adamantly against compressed MP3 music streaming, arguing that not only does it leave listeners only a sliver of a recording’s potential, but that it is poisoning our brains, as he discusses in a New York Times Magazine article. After the downfall of his own digital music company, Pono, Young has lauded Amazon’s new high fidelity music streaming service.

“Earth will be changed forever when Amazon introduces high-quality streaming to the masses,” said Young in a press release. “This will be the biggest thing to happen in music since the introduction of digital audio 40 years ago.” In the Times Magazine article, author David Samuels compared Young’s feelings toward music streaming quality to walking into the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see that artwork by Gustave Courbet or Vincent van Gogh was replaced by pixelated thumbnails.

David Samuels’s September 2019 New York Times Magazine feature about Neil Young and his fight for high quality music streaming.

Like Young, Barra says she is concerned that the listeners will miss out on high quality playback, even if they don’t know what they’re missing. Barra worries that people will not be able to experience the full capability of a high fidelity recording, especially with the increasing popularity of smart speakers.

“On one hand, I think that it’s a really important conversation to be having, and that it’s in every artist’s best interest to give people the best representation of their art,” she says. “But in the same breath, there’s a huge spectrum of places that your music is going to be played. And most people’s playback situation is going to lack. They’re not even going to be able to hear that file to its fullest fidelity.”

Whether or not the four instructors will use high fidelity streaming is split. Slade sees the high fidelity feature as more of a marketing device than anything and says he will be sticking to Spotify for now.

“The difference in terms of what I’m hearing is, one, not great enough for me to pay the extra money,” he says. “Two, somebody might put me down for this, but I actually preferred the Spotify sound. … I just liked it better and the platform is easy and it’s 10 bucks a month and it gives me everything I need.”

Alexander would rather focus on artistry rather than increasing fidelity.

“I don’t know that it’s worth it,” he says. “I’d rather spend my energy making a great song than fighting about how you’re going to receive it. If it’s a great song, it should cut through all platforms in a way that communicates to the individual.”

Though Barra says most people don’t pick up the details on high resolution playback, it doesn’t mean they can’t learn.

“I do think it’s our responsibility as the music makers, or the people that are leading this dialogue, to think about ways to swing back in that other direction so that high fidelity music listening is important and culturally relevant again,” she says. “So I think that it’s important that we encourage people to learn how to listen and care.”

She says one way to improve your listening skills is to “A/B” a song, meaning conduct a side-by-side comparison with a high resolution recording and a regular MP3 recording.

“You could listen to the highs, and just focus on the shimmery sort of hi-hats, and synths, and just focus in on those types of sounds,” she says. “Then listen to the next recording, and try to focus in the same way and see if you can hear the difference.”

As for Wyner, he says high fidelity streaming is a move in the right direction for the music industry. In an ideal situation, he says streaming quality will correlate with appropriate pricing for the consumer and compensation for artists and creators.

“Any time a music distributor, whether that be Apple, TIDAL, or in this case Amazon, sees value in talking about high quality, that they think people might want to spend money on quality of music, I think that’s a really positive message for the world,” he says. “Getting people to pay for music is really the issue here.”

Explore courses authored and taught by Prince Charles Alexander (Vocal Production), Erin Barra (Music Production Fundamentals for Songwriters), Sean Slade (Music Production Analysis), and Jonathan Wyner (Audio Mastering Techniques). Enhance your critical listening skills with the Berklee Online course Basic Ear Training.