Understand How Song Copyright Works and Why Registration Protects Your Music and Creative Rights

The following information on how to copyright a song is excerpted from the Berklee Online course Music Business Law for Artists, written by Valerie Lovely, and currently enrolling.

If you’re stumbling upon this article without any previous music business law context, I suggest you read my previous post, Music Business Law Facts Every Musician Needs to Know. And once you’ve read that, you’ll have the necessary background on how to copyright a song.

Are you all caught up? Okay, as far as how to copyright a song, the good news is that copyrights are extremely easy to create. In fact, you have already created thousands of copyrightable works on your own and probably have collaborated on hundreds of others. A copyright automatically exists at the moment something original is created and fixed in a tangible format. Let’s break that down.

Originality

The work must be the result of an author’s original creative efforts. The creator does not have the burden of researching whether there is anything in existence that could be similar to what they created, but their creation may not be copied from something already in existence, either consciously or subconsciously.

Fixed

The work must be fixed in a tangible format so that it can be perceived visually or with the aid of a machine or device. Playing music live for someone would lack that fixed element. An easy test of whether the work is fixed is if you can easily share a copy of the work (e.g., paper, MP3, etc.) with someone else.

STUDY COPYRIGHT LAW WITH BERKLEE ONLINE

This rule makes sense after you learn that copyright protection can last for many decades. When you have a fixed copy of the work to refer to, it should remove all potential ambiguity.

One Song, Two Copyrights

One quirk of music copyrights is that we divide them into protection for the song composition © and protection for sound recordings ℗. The entire music business has been divided accordingly for decades. The music publishing industry is focussed on generating interest and revenue from the song compositions, and the recording industry is focussed on the same for the sound recordings. From this point forward, it will be very important to always keep these two sides of copyright in mind.

The Song Composition

Copyright in the song composition protects the combination of aspects like the melody, harmony, and lyrics. One way to conceptualize this is to think about the song composition as what is included on a piece of sheet music. It provides the basic melody and establishes the fundamental character of the work.

The Rights in the Sound Recording

Sound recording copyrights are created each time a song composition is recorded. Each performance will be original and, when recorded, fixed in a tangible format. When identifying the rights owners in a sound recording, ownership in a particular sound recording is represented by the ℗ symbol.

Administrative Paperwork

Solo artists often enter into projects believing they will have full ownership of their song compositions and sound recordings. They paid for the studio time. They brought songs they had been working on for years to the recording sessions. They paid the musicians and producers for their services. The project is being released under their name. It all seems right—but it is not.

Unfortunately, if you ignore business and legal matters, situations can get complicated.

Song Collaborations

Making music is often a collaborative process—especially songwriting. It’s easy for people to work together, share suggestions, and add their creative input into a song. They are usually not thinking about paperwork (but they should be!). However, in the absence of an agreement, when two or more people are collaborating with the intent that their contributions blend into what will become the song, it is considered a joint work.

For joint works, the default rule under copyright law is that:

- everyone that contributed is an equal owner of the final work

- any revenue will be divided equally amongst the number of owners

- any of the owners may license the work for any purpose without needing the approval of the others

The exception to the last point is if a license prevents the other owners from being able to make a similar or any deal; all of the owners must agree to the license. For example, if one owner has an opportunity to issue an exclusive 10-year license that would prevent the others from licensing that song for the next 10 years, all of the owners must agree to the license.

Ownership, Administration, Revenue (OAR)

Therefore, to avoid the default rules under copyright law, whenever copyrights are being created, there are three topics that must be discussed, captured in a written agreement, and signed by all of the contributors. They are ownership, administration, and revenue.

- Ownership: Deciding who will own the copyrights in the song compositions and/or the sound recordings and in what shares.

- Administration: Deciding who is authorized to negotiate and sign deals for the use of the song. This administrator usually handles filing copyright registrations as well as making sure that all royalties are being collected and distributed according to plan.

- Revenue: Deciding who will receive revenue from the song compositions and/or the sound recordings and in what shares.

You might remember this as: either you take care of business the way you choose, OAR the Copyright Act will kick in with its defaults and they may not be what you want. These three topics can and should be addressed separately to arrive at the best solution for each project. One does not need to be an owner to receive revenue from the work. One does not need to actually be a songwriter to be listed as an owner and receive revenue. These are contractual terms. Whatever the parties agree to is what will be binding upon the parties.

For the solo artist we mentioned earlier, it might look like this:

- Ownership: Artist owns 100 percent of the compositions and sound recordings.

- Administration: Artist administers 100 percent of the rights in the compositions and sound recordings.

- Revenue: Artist receives 100 percent of the composition and sound recording revenue.

A pop band collaborating with a producer on one song might end up with this breakdown:

- Ownership: Band owns 60 percent of the composition, 20 percent is owned by the producer, and 20 percent is owned by a collaborating songwriter. The band owns 100 percent of the sound recording rights.

- Administration: Band administers 100 percent of the rights in the composition and sound recording.

- Revenue: The composition revenue is divided amongst the band 60 percent, producer 20 percent, and songwriter 20 percent. Producer receives 10 percent of the sound recording revenue, band receives the other 90 percent.

Split Sheets

One way to take care of the business of who the owners are, who is entitled to make decisions, and who receives money from the project is to prepare a songwriting split sheet for each completed song. This allows all contributors to discuss and decide exactly how to divide up songwriting ownership and revenue. It can also be adapted to include sound recording splits as well.

Collaboration Agreements

It isn’t unusual for creative teams to develop ongoing working relationships. These may take a variety of forms, but when a pattern of collaboration develops, it benefits both parties to draft an agreement that clarifies their expectations. It’s an ongoing agreement, so the issues of ownership, administration, and revenue are established for any work created together during the term. Typically the term lasts until a specified period of time after either party gives notice to the other party of their desire to end it.

Some examples of collaborative relationships include:

- Two songwriters—one has a talent for writing music and the other has a talent for adding the lyrics. They divide all music 60/40.

- A producer and artist that collaborate remotely through a cloud-shared folder over time. Producer creates tracks, songwriting artist picks what they like and records topline over it, producer adds parts, artist adds parts, etc. They do a 20/80 split.

- Two songwriting performers that create music together in real time just by bouncing ideas off each other. They do a 50/50 split.

Work-Made-for-Hire Forms

The definition of a work made for hire isn’t always a perfect fit for the situations musicians find themselves in. But the artist who is employing musicians, producers, arrangers, etc. for recording sessions should still have everyone complete a work-made-for-hire form. This makes it clear that the expectation is that the artist will own 100 percent of the copyrights from everyone’s creative efforts at the moment they are created.

A work-made-for-hire form should always include a copyright transfer clause—just in case the definition of work made for hire doesn’t fit the situation. It would basically state, if this is not considered a work- made- for- hire under applicable copyright law, the intention is that all rights in the work be transferred to the artist and that the contributor agrees that if any future paperwork needs to be signed to make this happen, they will comply.

Authors automatically obtain copyrights after creating an original work that is fixed in a tangible form, and they are able to control the exclusive rights in the work. However, to enforce those rights, they must have a registration filed with the US Copyright Office to show proof of their ownership.

Copyright Registration Options

Understanding the terminology and rules helps with deciding which form is the best for a particular project.

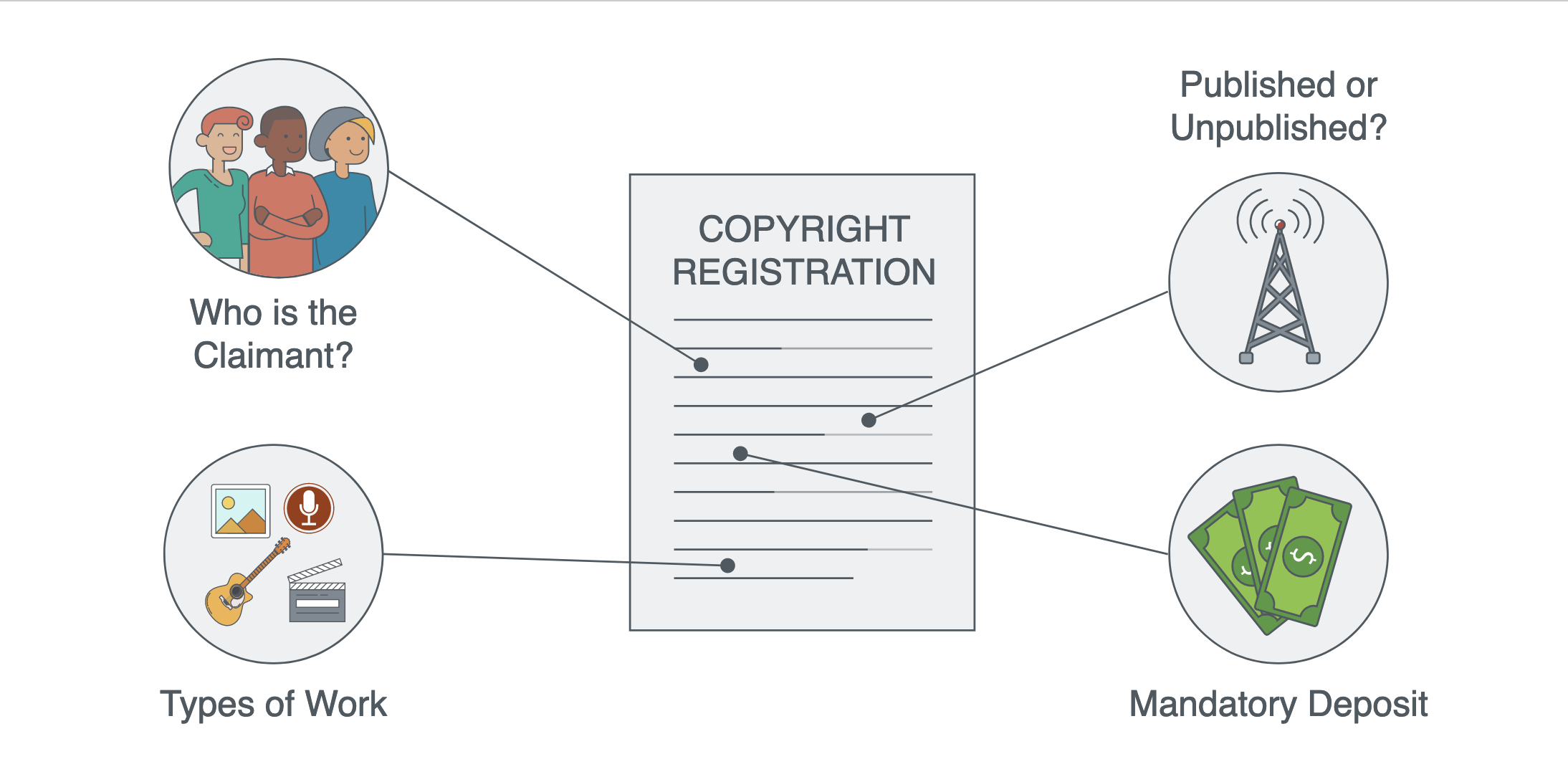

The claimant is the person claiming ownership in the work. It could be the author, who obtained the rights when they finished the work. If the author is not the claimant, the Copyright Office needs to know how ownership was conveyed. The two options are work- made- for- hire and written transfer.

There isn’t a place on the registration form that asks for the shares of the copyright that each owns because the Copyright Act presumes that whenever people get together to create something, they intend to share ownership and revenue equally regardless of individual contributions.

Published or unpublished is referring to whether the work has been released to the public or not.

Types of work: The Copyright Office separates creative works into different categories.

- The Work of the Performing Arts category would apply when filing a registration for the song composition.

- The Sound Recordings category would apply when filing a registration for a sound recording; however, in some cases, when the authors or owners of the song composition and sound recording are identical, one sound recording registration can be filed to include both sides.

- The Work of the Visual Arts category would apply when filing a registration for album art or photography.

- The Motion Picture or Audio Visual Work category would apply when filing a registration for a music video, concert video, documentary, animation, or other film or multimedia project.

Mandatory Deposit Requirement

Two copies of works that have been released to the public must be provided to the Copyright Office within three months of their release for use by the Library of Congress. Even if a copyright has not been filed, the deposit must be made unless the project was only distributed as a phonorecord or digitally. In those cases, it would be exempt from the mandatory deposit requirement.

The final step in the copyright registration process is providing a deposit copy of the work. If the music was released tangibly as an album or CD, two copies must be mailed in the format that was released to the public (e.g., album art, liner notes, inserts, etc.). If the project was only released digitally, those files can be uploaded to the Copyright Office. The deposit that accompanies a copyright registration satisfies the mandatory deposit requirement when it is required.

Copyright Registration Forms

The US Copyright Office has a number of registration options for particular purposes. These are accurate at the time of this writing but the Copyright Office regularly reviews their registration formats, updates procedures, adds/replaces registration forms, and discontinues those that aren’t functioning well. It’s best to visit the copyright office to review their current offerings.

Group Registration for Unpublished Works (GRUW): One registration can be filed to protect up to 10 compositions and their sound recordings if the authors and owners are identical on all of the works. If the authors and owners of all of the songs are the same but different from the authors and owners of the sound recordings, up to 10 unpublished songs can be filed together on one registration and up to 10 unpublished sound recordings can be filed with a separate registration.

The Copyright Office provides information about this option in Circular 24.

The Group Registration for Works on an Album of Music (GRAM): This form is a great option for a published album but it isn’t possible to file one registration for the compositions and sound recordings; they must be filed separately. The GRAM allows up to 20 song compositions that were released as an album to be listed in one filing. It allows up to 20 sound recordings as well as their accompanying album art, liner notes, and photography that were released as an album to be included in one GRAM filing.

The Copyright Office provides information about this option in Circular 58.

The Standard Registration: This registration is used when none of the other special registrations fit. It can only be used to file one song at a time. A registration that includes both the composition and sound recording may be filed under one form, but only if the authors or owners are the same for both.

In this video, the Copyright Office explains how to complete the Standard Registration form.

The Single Application: The single application is also referred to as the “one work by one author” form. It works best for solo songwriters that record their own music and want to file their songs individually. It can only be used to file one song that was entirely created and is owned by that same one person. It cannot be a work made for hire.

One unusual aspect of this filing is that everything submitted to the Copyright Office as part of the registration must have been created by that same one person—even if material is excluded from the actual registration.

For example, let’s say Angel is a songwriter who doesn’t record their own music; they hire musicians to record their demos. If Angel wants to use the single application to protect just their song composition, they cannot submit the demo recording as the deposit because they did not personally create all of the elements they are submitting to the Copyright Office. Angel would need to either create their own sound recording, performing all of the parts, or submit sheet music for the deposit.

In this video, the Copyright Office explains how to complete the Single Application form.

Public Domain

When a work is in the public domain, anyone can use it without needing to ask permission, pay fees, or share royalties. In the United States, most works created by the government do not get copyright protection. They immediately enter the public domain. Works that obtained copyright protection have a limited duration. When they expire, they enter the public domain.

Beware of Scams

Copyright registrations are public records. There are companies that identify artists who have recently had a copyright registration issued for their sound recordings and compositions. They contact the artist, greet them by name, compliment them on their music, and state a desire to pitch one or two of those recently filed songs (they will use the actual song titles from the registration) to their contacts at Sony, Universal, or Warner. But to do so, they need a check for $247.50 (or some odd number in that range) per song to cover their costs. They share that there is no risk to the artist because the label will make the offer directly to the artist. These are scams, and none of your favorite successful artists has ever made it big through this process.

As we said at the end of the previous article about music business law, this is all a lot to process. And while it may at first seem counterintuitive to the idea of having fun, being creative, and making music, you’ll find that if you take your time to study and learn all of this information now, then the actual amount of time you’re spending on how to copyright a song is still a lot less than the amount of time you’re spending making music.

For more information on the basics, take Music Business Law for Artists. If you’re ready for an even deeper dive, take Music Business Law.