Music is My Life: Episode 002

Sarah Neufeld on Arcade Fire, Bell Orchestre, and Collaborating with Husband Colin Stetson

How Sarah Neufeld Bridged Arcade Fire, Bell Orchestre, and Experimental Violin with Colin Stetson

Sarah Neufeld began playing violin at the age of three, and considers herself “half-classically trained.” In the second episode of this podcast from Berklee Online, she shares how she came to be a member of Arcade Fire, and how she and her husband Colin Stetson approach collaborating with one another.

Sarah Neufeld: I’m half classically trained. So, because it means such different things to people, what is musical education? I started out as a very small Suzuki kid, a three-year-old. And I was dying to play at that age. And we had a strong little Suzuki community in the small town that I grew up in. So I did that until I was 12.

And then I took a few years in a more traditional classical setting in a town that was a couple hours away, because I really did live in a small place and there wasn’t a lot to choose from. And so I had to travel for the more serious lessons. At that point, I’d always been really into improvising over the practice of repertoire. And at that point, I was getting into my early teens and feeling not super aligned with the stuff that I was playing or even just the environment of the education—the classical education I was receiving.

It was definitely one of those teenage—like well, “I’m going to play the guitar and sing and be in a band.” But I meant it, and I really did want to do that. I did actually quit the violin and took guitar lessons and learned all of the Hendrix solos that I could, and then a few years into that, realized that I had this facility on the violin that I would probably never have on anything else given the amount of hours I’d spent working on it.

And I realized, well, I can do whatever I want with this thing, really. I mean, nobody’s telling me not to. So I integrated that into that fun—more fun, free, fluid, compositional zone. And then I ended up picking it back up in a more formal way in university and studied jazz. I had a technique teacher that was both jazz and classical.

So I actually got my ass seriously kicked for those key few years in my early ‘20s, which was great, because even though I have, again, really gone my own way with it, I’ve held onto just the daily scales and rudimentary exercises that keep you fluid. And you need the fluidity on an instrument like—any instrument, but a fretless bowed instrument, especially.

Neufeld says that her time away from the classical training rigmarole helped her take a more relaxed approach when collaborating with others.

This is all a long time ago. I think I was maybe 14, 15. But I was really excited about theater. I was really excited about dance. I’d always done a lot of—I’d been in many performing arts. So I just simply shifted gears into more dance, more theater, and then learning guitar and playing music with other people in a much more relaxed setting than say, 7:00 AM orchestra practice.

So I didn’t really feel like I was losing. I was gaining things. I wasn’t losing a thing. But yeah, it didn’t last that long. I picked it up again quite quickly. It’s not like I went years without playing it at all.

We had a really musical neighborhood. And we’d have these total neighborhood hoedowns. We’d play all of the oldies we could think of. They always wanted jigs. I knew a few of those, as any good violin student does.

Neufeld says that it was during her time at university that she discovered her identity as a musician. However, it wasn’t necessarily the classes she was taking as much as it was the classmates she had begun to play within her free time.

I discovered this way of playing maybe through some improvised collaborations in my time in university and this group I formed early on called Bell Orchestre. We were influenced by a lot of different stuff, but—the Rachel’s, Penguin Cafe Orchestra, Steve Reich, Tortoise, all this stuff that was mixed up together and that wasn’t necessarily classical. It wasn’t jazz. It wasn’t rock. It was influenced by everything. And it was sometimes called ‘post-rock.’

But that’s where I started playing really chordally. We didn’t have guitar in the band. We didn’t say, “Okay, you’re going to play as if you’re the guitar in this setting.” But that’s what I was gravitating towards. I get really excited with the harmonic combinations that you can create on any given instrument.

And the violin you can play chordally and you have to arpeggiate with the bow a little bit. But then using different pressure and different intention with your bow arm, you can create totally different feelings. It’s pretty wide open in terms of what you can do chordally, I think, even though there’s only four strings and it’s fifths, and all that. But yeah, I sort of discovered that through my collaboration with Bell Orchestre and then on and on and on throughout the years, leading me to where I began to make solo records.

And playing with Bell Orchestre led to an invitation for Neufeld to join a band you might have heard of, Arcade Fire.

So Richard Parry and I formed sort of a union of playing music together really early on in 1999. And we were invited to play with a dance— I guess a dance project in Concordia. And we were introduced to this drummer, Stefan Schneider, who’s playing with me tonight. And so the three of us—that was early days—formed Bell Orchestre. And then that grew into a couple years of different projects and more people.

At that point, say 2002-ish, Richard was also involved in the recording department. He got to know a couple people that were in the early incarnation of Arcade Fire. And he went and recorded the EP one summer and came back really involved and was playing with them. And throughout that year, into 2003, I got involved.

I mean, Montreal’s a small scene, a small city, especially in the English sort of music kid school. This was a long time ago, too. I feel like it’s bigger now or I don’t know anybody or something. But yeah, back then, it was like, “You’re playing with those guys? Oh, me too. I really want to.”

I got to come along into the making of Funeral, which was a really nice moment. I mean, I had seen them play a couple times live and it was really touching. The music that would be Funeral really lent itself really well to strings. And I felt really naturally disposed to playing on those songs.

Neufeld says it was around this time that she realized she could have a sustainable career in music. But it wasn’t necessarily a Eureka moment.

I don’t know if I’ve ever necessarily felt like that black and white about that. But it was more a question of, “Hey, can I come and play?” “Hey, do you want to come play with us?” and “Yeah, let’s.” We tested it out and it worked. And it sounded good. And we had fun. And one show led into a tour, led into the release tour into many, many years of playing together.

Bell Orchestra was definitely—we were taking steps forward to become sustainable as well, although it was a lot different and slower, more niche for sure. But we were taking steps to—in Canada, we have these wonderful systems and government grants and artist support. So we were getting into those channels and doing residencies and all this stuff.

So it did feel like we were putting one foot in front of the other and we would somehow become sustainable. But then, Arcade Fire became sustainable a lot quicker. Yeah, that was the first time I’d ever not had, like, five Joe jobs at the same time, Oregon tree planting in the summers.

Neufeld did, however, have a Eureka moment about quitting her job planting trees.

Canada and the states are so close together, but tree planting isn’t a thing here the way it is in Canada. And what a lot of people that are tough enough physically and mentally to do, go off in the summer and you live in a tent and you work, it’s piecework. And you work in clearcuts.

You work in rugged northern land in all sorts of terrible weather and carrying 50 pounds of little wet, cold, tiny trees on your hips, bending over, digging holes, climbing over logs and up mountains. And so I did that for six summers. That’s how I sort of half put myself through school and through part of being in bands.

The last summer I tree-planted was the summer right before we released Funeral. So I was saving up money to go on tour. And I remember getting a hand infection. And that was it for me. It’s pretty easy to get messed up hands cramming them into dirt with lots of chemicals and sharp tools all day long. And I was like, “I’m a violinist. This is bad.”

And since that day that Neufeld declared herself a violinist and not a tree planter on the side, she has undertaken several different projects, each one requiring a different shade of herself.

Those three projects and then my solo project are all so different. I’ll work backwards. So with Colin and I, we created the duo as a real experiment or journey into the idea that we could be our individual solo voices put together, because we know each other’s music so well. I mean, we have a life together. And we’ve influenced each other’s compositions and just development as artists over the years so much.

And we’re also just—yeah, we understand, I think, the way each other works and the potential. And so we always wanted to put those two together. I mean, my solo voice is a lot newer and younger. And so I think we—after my first album, felt like, “Ah, we’re at the point now where we could actually physically layer these two together and see what happens.” So we are bringing almost exactly the same thing to the table, to the duo table, as the solo table.

There’s slight tweaks here and there, of course. The marriage of violin and all the saxophonics he does, they don’t work on all the same instruments, all at the same time, just the different harmonics and tonalities of the instruments. But that is a pretty full on representation of both of our max solo potentials at the same time. And I think it works really beautifully. And it’s palpable.

And then Bell Orchestre, there’s a lot of voices. And we all equally bring our improvisatory sensibilities and also a lot of listening. And because there’s no one leader, there’s no one idea of, like, “We’re going to create something that sounds like this.” We’re always discovering and trying to be surprised. And so our work actually takes a long time, I think, because of that.

But we’re all arriving together. I always referred to us as the six-headed dog, like, rawr, super crazy, going around in circles, and then arriving, ultimately, at something really beautiful, strange, and quite unique. And I’m bringing myself to that equally with everybody else. I don’t play as full on all the time. There’s a lot more space. There’s a lot more going on, right? So there’s more giving and receiving.

And then Arcade Fire is a whole other beast of a thing. And it’s really driven by Win and Régine writing the songs. There’s a lot of arrangement that happens in the band. I come in and I do quite a small thing in that band. I don’t really employ a lot of my individualistic technique. I’m playing string stuff.

And it’s really nice. It’s quite relaxing to play like that. And I’m serving the bigger group more, like doing backup vocals and playing tambourine when that’s what is called for, and playing synth when that’s what is called for. It’s just kind of filling a role that needs to be filled. It’s super, super fun.

Neufeld refers to her collaboration with saxophonist husband, Colin Stetson, as an experiment to see if their very unique individual sounds would sound good together. They had collaborated before their 2015 album, Never Were the Way She Was, which I might like to take a moment to editorialize is a truly dizzying album.

Something about the way that the two instruments hit my ears together just knocks me off balance and well, basically, it kind of melts my emotional core or something. It’s just really, really effective stuff. Anyway, Neufeld says that it was this album that marked a collaborative milestone for the couple.

Colin and I met in the musical setting. Bell Orchestre was playing. He was playing with Antibalas. We were impressed with each other’s, I think, dynamic performative qualities as musicians. We’d never met each other. We had no idea who each other was. We saw each other perform.

There’s something we have in common as performers. There is sort of an intensity and a physicality. I think we’d been waiting for the right time to collaborate in a really intense, one-on-one duo way.

We have collaborated tons in various projects together. He’s collaborated within Bell Orchestre. I’ve collaborated within other groups of his. And we had done soundtrack work before our duo record. I think that we had arrived at the moment where we were able to put our voices strongly together.

Yeah, I mean, collaborating in a couple—I think it’s pretty typical stuff. It’s like you have to watch your boundaries. And you know how couples tend to let emotionality come into things a little bit more, which can be a hindrance, but it can also be a bonus because you can get more emotion. I think there’s a lot of emotion in our music.

And it’s just like little stuff with people that work together, that live together. You can get pettier than— like, “Honey, you would never say that to me if I was your bandmate,” that kind of stuff. But you just have to appreciate each other, and also watch yourself and create maybe more boundaries than you have normally in your relationship, because you don’t want to step on each other too much. It’s a precious thing.

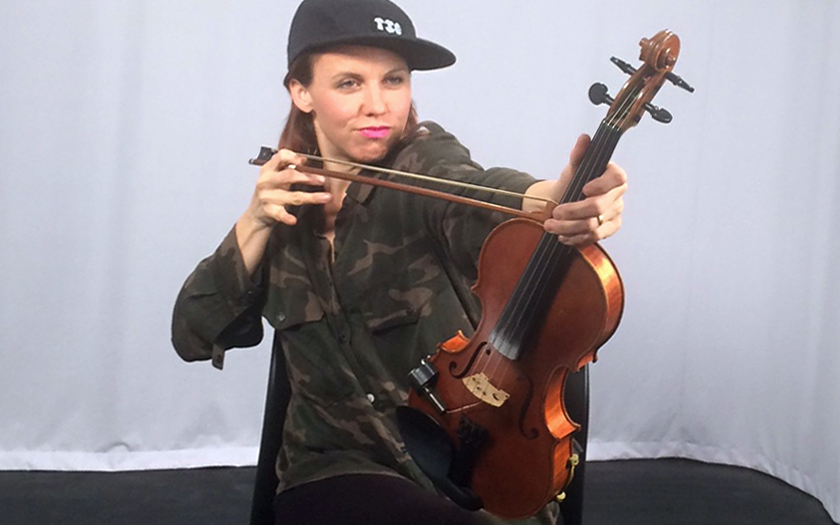

Speaking of precious things, here’s what Neufeld has to say about her violin of choice.

I got this instrument when I was making my first solo record in 2013. The woman at the shop on the Upper West Side in New York City wouldn’t ever tell me who made them or how much they were or what year they were from. She just wanted me to find something that I really liked.

And so I played a lot of them. And I always like big bodied, low end sounding instruments. And all of the ones I ended up liking were often American and modern, which was—I had no idea I had a preference for that. I didn’t know there was a trend, even. But yeah, this is Nathaniel Rowan from 2007. He was based in Brooklyn, but he is, I think, of German origin.

I asked her to describe the composition process of the title track of her 2016 album, “The Ridge,” in particular, whether or not the frantic intro of that song is something that she came across by experimenting with different patterns or if she was just chasing a feeling within.

With a piece like “The Ridge,” I was chasing something that I felt in my mind. It’s very minor. And I didn’t want to stay there. I wanted a dramatic harmonic shift that felt like sun breaking through clouds, but still really tense and urgent. And so that’s how I landed at going from that tonal world to that kind of A majorness. And if you were just jamming out on your fretboard on a violin, you wouldn’t necessarily arrive at that, because it’s just awkward. A lot of string players rely heavily on open chord structures, because why wouldn’t you? But there’s also the challenge of wanting to push past the comfort level of the instrument.

But yeah, I’m also really drawn to all sharps or all flats, just in terms of the feeling, you know? You get different feelings with different keys. And so with that, I knew there had to be this long harmonic exploration within that piece. And I knew that it had to be all chords, all the time to satisfy that reach.

Another satisfying reach in Neufeld’s life? When Arcade Fire fans come around to explore her solo music.

I always think of it as just something that can open doors. People will only come through the door if they’re interested and want to and are ignited by what’s in the door. But they might not see the door otherwise. So it’s been a really great thing to have as an invitation to maybe more of a diverse audience than I would normally within the realm of experimental music.

Having the access to a lot of kids or just a lot of rock music lovers will discover Richie’s music, my music, Bell Orchestre, Colin’s music. A lot of us are into more experimental or new music. And yeah, some people will walk through that door and they’ll stay there and they’ll really want to engage with it. I think it’s a real blessing.