The following information on movie scores is excerpted from the Berklee Online course Music Composition for Film and TV 1, written by Ben Newhouse, and currently enrolling.

When you go to a concert, the primary audio element is the music. When you go to a movie, the music must share the airwaves with dialogue and sound effects. (In many cases, the director and/or producer will consider those elements to be more important than the music.) An effective movie score will take into account these other audio elements, considering them to be much like a counterpoint to the music.

Dialogue and the Movie Score

In most cases, the movie score should make an effort to avoid the dialogue. Typically, the dialogue directly delivers the plot to the audience and most producers/directors deem that to be more important than the music and sound effects. In the case that music or sound effects should distract from an important line of dialogue, the music or sound effects will likely be removed entirely.

Example: ‘Troy’ (2004)

Notice how the music interacts with the dialogue. As the graphics begin,

the only film scoring is a drone, vocalizations, and intermittent drum hits.

After the opening graphics, a voice-over enters. Observe how carefully the drum hits are placed around the pauses in the voice-over. When the voice-over ends, the drums pick up again. At the end of the scene, the music stops entirely when the discussion between the two kings begins, allowing the audience to focus entirely on the dialogue.

Sound Effects and the Movie Score

Just like dialogue, the composer should consider the sound effects in their composing process and treat them as ideas that act as counterpoint to the music. Some considerations when working with sound effects:

- In scenes that are heavy with sound effects, consider using no music at all: gun fights, car chases, bombs detonating, etc. Such scenes often fill the air with sounds of clashing metal and explosions. In many cases, those effects are extremely detailed and sufficient to drive the energy of the scene themselves.

- In scenes with clashing metal, consider limiting your percussion. Clashing swords and similar sounds directly compete with cymbal crashes. Often, action music built primarily with driving strings and brass work better for such scenes than music that’s predominately percussion.

- It is not the role of music to literally recreate the sounds of events on the screen. The composer need not—and should not—put a cymbal crash and bass drum hit at the moment of a big explosion. Literally portraying that explosion is the job of the sound effects, not film scoring. The music, on the other hand, should portray the emotional implications of that explosion.

Example: ‘Cold Mountain’ (2003)

Notice before the explosion, when the northern troops are placing explosives beneath the southern troop positions in this Civil War epic, the music is a suspenseful drone with improvisatory fiddling. During the explosion, the music stops entirely. After the explosion, the music reenters as a poignant piano solo. Here, the sound effects portray the literal events on the screen while the music portrays the emotional events.

Visual Effects and the Movie Score

By definition, the discipline of film scoring involves aligning music with

visual images on screen. This means the composer must make a series of

decisions regarding the timing of the music—when the music should start, stop, and change emphasis.

Entrances and Exits

Music should start/stop when there is a change in the emphasis and meaning of the picture. Such a change can be initiated by:

- a shift in dialogue

- a change in camera position

- a change in setting, and/or the action (such as a car driving off or a character discovering an opened door)

Example: ‘The Green Mile’ (1999)

Notice the music enters when the setting changes—shifting from the main character’s bathroom to the halls of his retirement home. Initially, the film score is source music, intended to sound like the soft background music often played over the speaker systems at retirement homes. The music changes with the next change in setting. As the main character leaves the retirement home for an outdoor walk, the music shifts from source music to orchestral score. The music exits with a last change in setting, as the main character reaches the destination of his walk and the scene shifts indoors to the retirement home

The emotional content of a film often changes within a scene and the music must match that contour. Typically, changes in the emotional content are

initiated by the techniques mentioned above—changes in dialogue, setting,

camera technique, and/or action.

Example: ‘Jurassic Park’ (1993)

Notice the music plays continuously. However, the film scoring contains multiple shifts that follow the contour of the scene. When the scene begins, the characters are on a helicopter ride to Jurassic Park, which (in the film) is located on an island off the coast of Costa Rica. During the helicopter ride, the music is up-tempo action/adventure music. This music conveys the upbeat and positive feeling of the helicopter journey.

When they first see the island, a heroic trumpet and brass theme enters. While the up-tempo energy of the music continues, the entrance of the brass theme matches the grandeur and epic nature of the scenery; jungle cliffs and towering waterfalls.

When the helicopter lands, the characters get in Jeeps and begin to explore the island. At this point, the music shifts to a light, up-tempo march—marking the shift from a helicopter ride to a terrestrial vehicle journey.

Toward the end of the scene, the characters encounter a real, live dinosaur. At this moment, the music shifts to a beautiful, reverent theme, marking the awesome revelation the characters are experiencing. This brings us to our next topic: pacing.

Pacing and the Movie Score

One of the primary tasks of the movie score is to match the pacing of the

music to the pacing of the visual images. The “tempo” of the visuals is determined by several factors, including the speed of picture cuts and the content of the on-screen action. While the tempo of the visuals cannot be described in precise beats per minute, they can be expressed generally (such as up-tempo or downtempo) and the music should match accordingly.

Think of any of the action sequences from the first Matrix movie. There are several shifts in the tempo of the visuals. Throughout much of each action sequence, when the characters are involved in a full-speed chase, the picture cuts move quickly. These moments are scored by intense, uptempo music. At other times, the action pauses—and the music slows accordingly.

Example: ‘The Matrix’ (1999)

Musical Characteristics

We looked at instances where the music changed in structure to follow contour shifts in a scene. This included changes in the instrumentation, tempo, harmony, and other aspects of the music. For brainstorming purposes, it is helpful to maintain a list of musical characteristics we can change when there is a shift in the picture, referring to the list when necessary while composing to picture. Below is one possible list:

- Make a change in instrumentation

- Move melody or other musical ideas from one instrument to another

- Increase overall instrumentation

- Decrease overall instrumentation

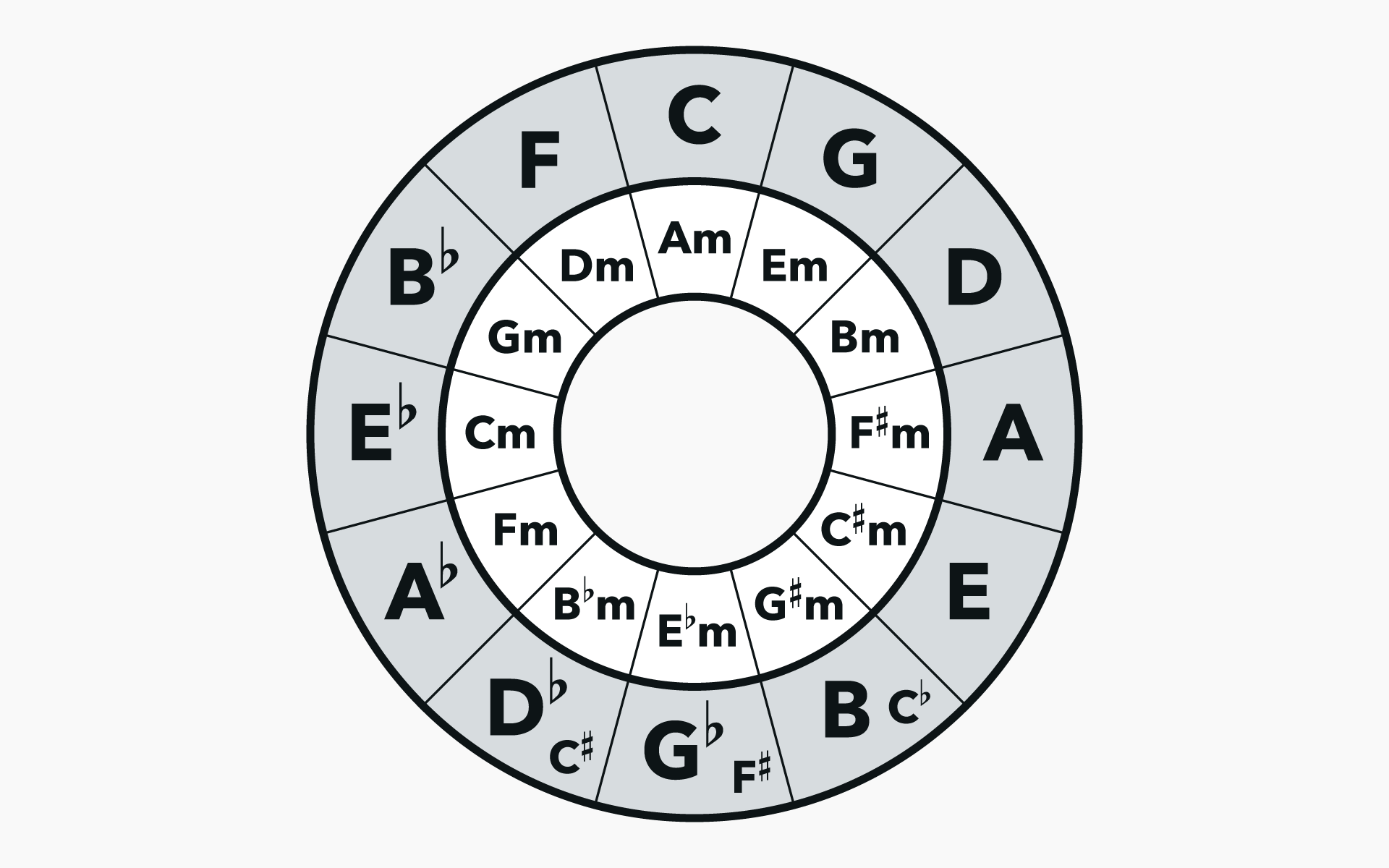

- Make a change in harmony

- Modulate to a new key

- Arrive at an important point in the progression, such as a resolution to tonic or a deceptive cadence

- Increase or decrease the harmonic rhythm

- Change the harmonic language, e.g. shift from a major to a minor key

- Make a rhythmic change

- Increase or decrease the tempo

- Change the meter

- Miscellaneous changes

- Stop the music entirely

- Start the music

- Switch to a new melody or musical idea entirely

- Change the counterpoint structure, e.g. move from a homophonic chord progression to a melody-countermelody-harmony structure

- Change the overall pitch register

Like much of what you’ve learned about composition, not all of these techniques need to be used simultaneously. Often, employing just one of the techniques above is sufficient for highlighting a shift in the contour of the picture.

STUDY MUSIC FOR FILM, TV, AND GAMES AT BERKLEE ONLINE