The following information on how to write a setlist is excerpted from the Berklee Online course Jazz Singing 201, written by Patrice Williamson and currently enrolling.

Setlists are essential for organizing and structuring a performance, ensuring that your music flows smoothly from one song to another, and energizes the audience in the way you want it to. They’re also crucial for making sure that everyone on stage is on the same page! When putting together a setlist, there are many factors to consider, such as the theme of the performance, the audience’s expectations, and your desired emotional or musical arc throughout the show. I’ll share how to prepare a setlist from my experience as a jazz vocalist, but these tips can apply to other genres as well.

Compiling Songs for Your Setlist

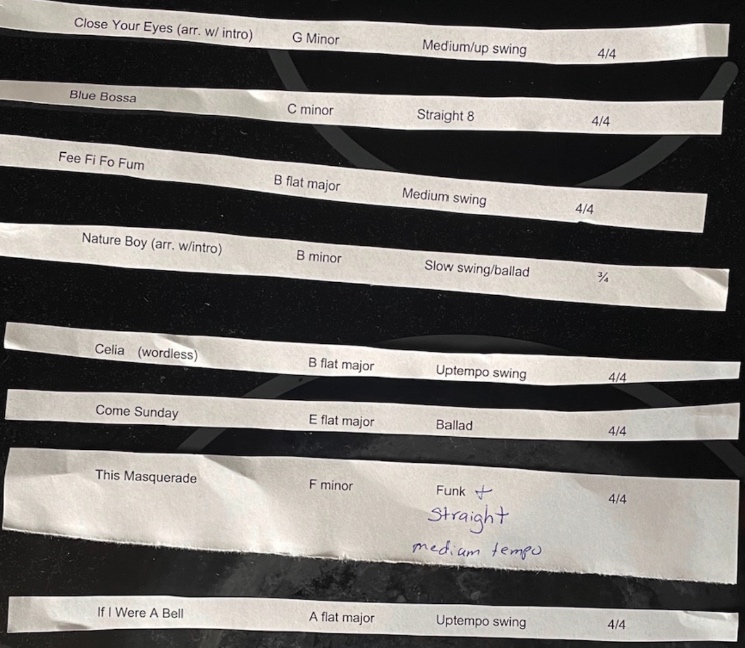

It’s important to have a list of all the songs in your repertoire. This means that before you even put together your setlist, you should compile all the songs you could conceivably play live. Information on the list should include the key, the meter, your preferred tempo and style (i.e., medium swing, uptempo swing, or ballad). Also, make note if the music to be shared with the band is an arrangement or a lead sheet. Having this at your fingertips will help you assemble your book and make last-minute gigs straightforward.

Your Gig Book

A “gig book” is a collection of songs in the key you’re most comfortable singing them. Be sure to amass a variety of songs in order to create a compelling setlist. It’s also important to have your book in digital format. These days I can AirDrop a chart to the band instantly, right before we play. And if my technology isn’t working, I always have a hard copy of my book with me so folks can take a picture of the lead sheet.

Lead Sheets

A lead sheet is the manuscript of a song in condensed form. The purpose of the lead sheet is to have all pertinent information contained on one or two pages. Information needed: harmonic progression/chord changes, melody, lyrics, meter, groove, and tempo. We find the structure or form of the song on conventional sheet music. Since many jazz standards come from Broadway shows, the score can be several pages long.

Where to Find Lead Sheets

There are countless publications available with hundreds of lead sheets. We often refer to these collections as “Fake Books” or “Real Books.” These days, the terms are interchangeable. The difference being that the original “Fake Books” were notorious for having incorrect chord changes and/or melodies. And “Real Books” were supposed to be correct.

If you can only find formal sheet music for a song, writing a lead sheet isn’t difficult. Begin by dividing each stave into four measures. Many jazz standards are 32 bars long, with 8 measures in the first and second A sections, 8 measures in the B section, and 8 measures in the final A section. Having a uniform number of measures per line is easy to see and keeps you from getting lost. At the beginning of the page, write in the clef, key signature, and time signature. The melody goes on the staff and the chord changes are above each measure. In the top left-hand corner, provide groove [i.e., medium swing, ballad, bossa, and tempo (BPM, which stands for beats per minute)]. If there are repeats, a dal segno, or a coda, be sure to highlight those directions so they are easy to spot.

Arranging Your Setlist

A good setlist has enough variety to keep everyone engaged. You want to avoid having too many similar songs back to back. Aspects to consider include key, groove, tempo, meter, instrumentation, and story. You also need to make sure you have more than enough music to cover the length of the gig. I always have more songs on the setlist than the allotted time will allow. This way, it’s easy to change the list at a moment’s notice without scrambling for a replacement song.

Here’s a method I’ve adopted over the years: I cut out each song title so I can move them around like puzzle pieces. I sing the beginning of each tune to suss out the flow and move the titles around until it feels right. When settling upon an order, it’s always a good idea to begin with a song you know very well. This will help you get acclimated and comfortable onstage.

Here are a few setlist options. Notice the differences from one song to the next. The shift may be with the key or the tonality, the groove, the meter, or the tempo.

Themed Setlist

Presenting a show around a subject or theme is a great way to publicize your performance. Try spotlighting your favorite artist, or programming songs from a certain era.

Say you have a performance in September, you could sing “September in the Rain,” “September Song,” “The September of My Years.” And if you’re in a part of the world where this month coincides with the fall season, you could include “Autumn in New York,” “Autumn Leaves,” “‘Tis Autumn.”

Another idea regarding a themed setlist is to have the song titles tell a story. In 2017, I released Comes Love, a tribute album to Ella Fitzgerald for the celebration of her centennial. The 12 songs on the recording present a narrative arc that reflects a woman’s journey from loneliness to love, and from lost love back to resilience and joy.

Song Structure

When rehearsing with your band or stepping onto the stage with a group of new players, you need to talk through the structure of the song, whether it’s a written arrangement or a lead sheet. How do you do that? Begin by answering the following questions:

- Do you want an introduction? If yes, what do you want?

- Do you want the full band in at the top of the tune?

- Do you want to sing part of the song with just piano or bass?

- For solos, should everyone take a full chorus?

- After solos, do you want to come back in at the top or at the bridge?

- How should the song end? With a tag? With an open vamp? Ritardando? Hard stop?

Here are a few tried-and-true practices:

- The last four or eight bars of a song works very well as an introduction.

- And repeating those same four or eight bars on the head out works well for a tag ending.

- A tag ending is when a certain number of bars are played three times in a row.

You will make many decisions on the spot, so giving non-verbal cues and conducting are crucial. When it’s time for solos, a wave of the hand is a great way to invite someone to play. Be sure to keep your attention focused on that person while they are soloing. If you want to come back in at the bridge of the song, come up with a hand signal or gesture. I usually tap the bridge of my nose. And if I want to come back in at the beginning of the song, I tap the top of my head.

Hopefully you now have a lot of new tips and methods to try out as you’re creating your next setlist. The next time you perform, make sure to take notes immediately after the show, identifying which song sequences created the crowd reaction that you wanted, and which ones you felt were lacking. The more you perform, the more you can refine and adapt your setlist to fit your needs. Creating a compelling and seamless setlist is an art, and an essential skill for any performer, regardless of the musical genre.

STUDY VOCAL PERFORMANCE AT BERKLEE ONLINE