This information about music modes is excerpted from the Berklee Online course Music Theory 301: Advanced Melody, Harmony, Rhythm, written by Paul Schmeling, and enrolling now. To read more about Paul, check out his bio at the end of this article.

The Construction of Major Music Modes

The term modal scales is applied to a group of scales commonly used in pop and jazz music. Music modes are different than the “regular” major and minor scales most students are familiar with. Each mode has a name, and mode names come from the Greek language and from a time before major and minor (as we know them) were clearly defined.

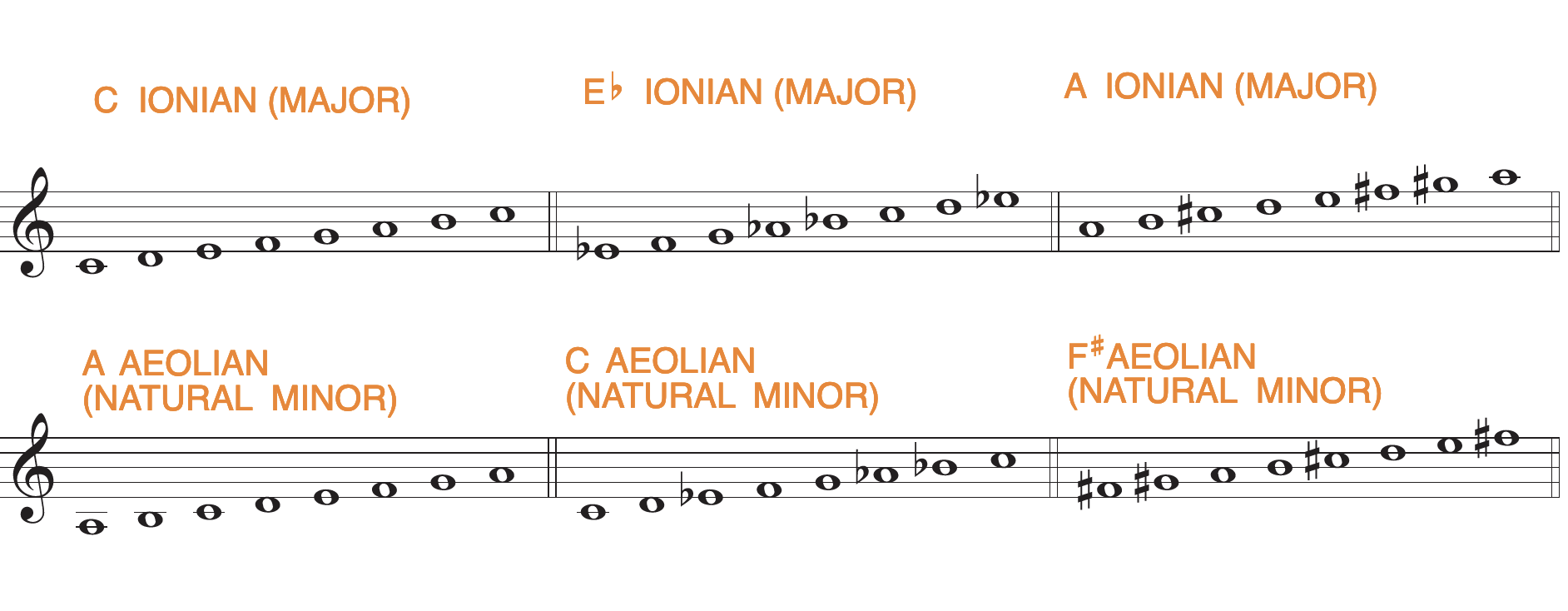

The scale we now know as major was originally called the Ionian mode and its relative minor was known as Aeolian.

We will use these two commonly known scales as a point of reference, as we look at the modal scales.

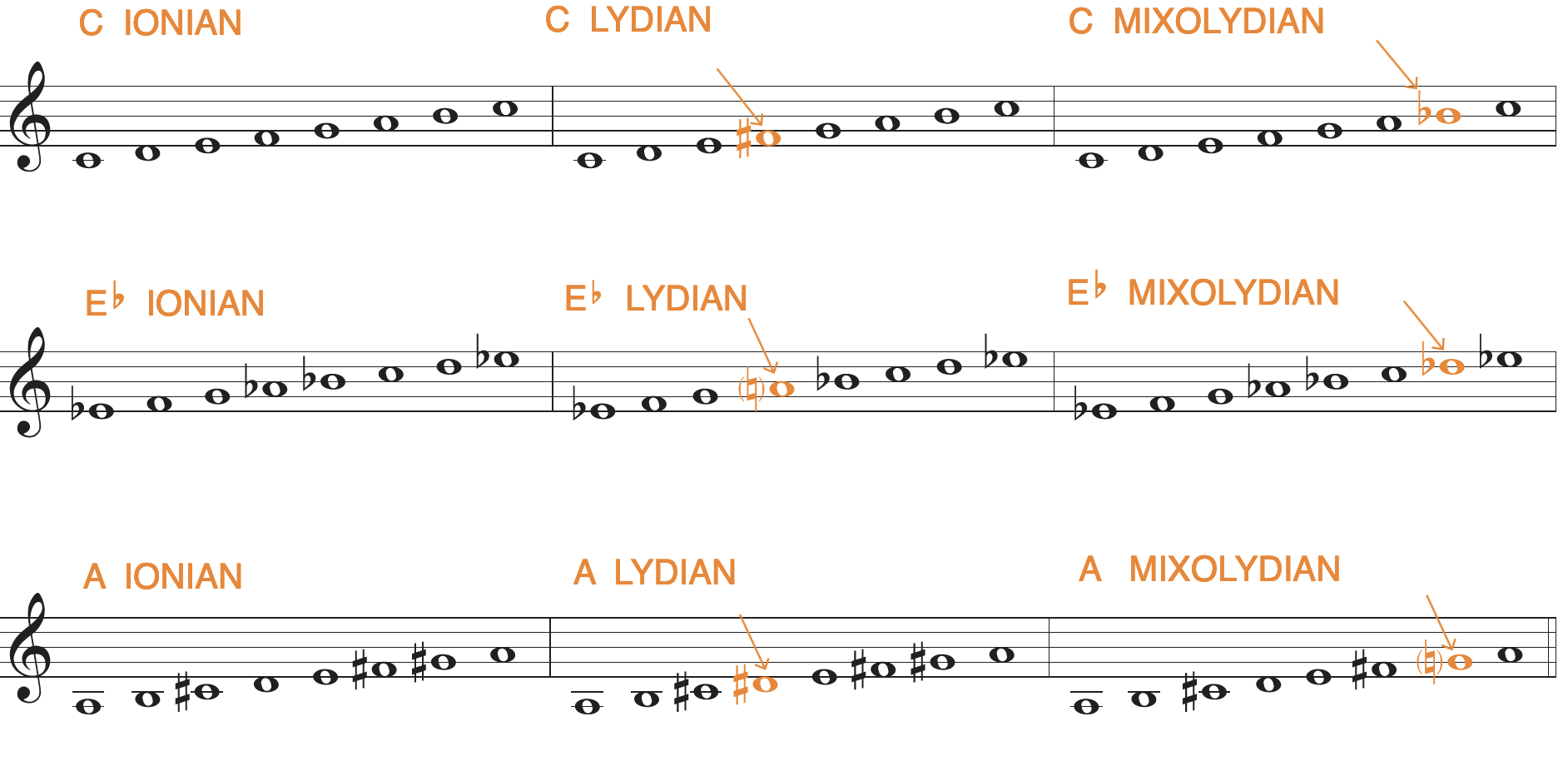

Major Modes: Ionian, Lydian, and Mixolydian

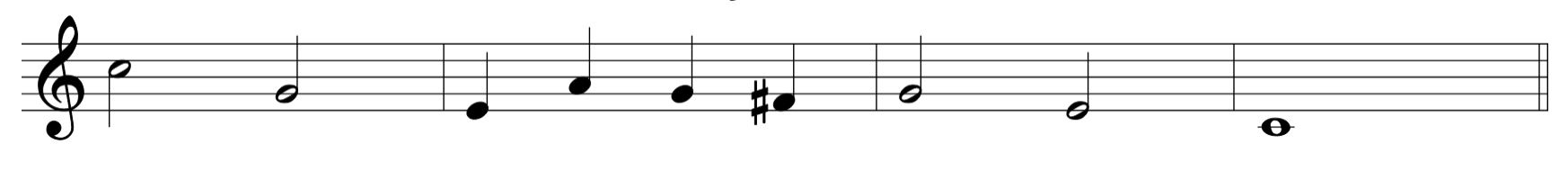

Let’s look at the three major music modes first: the Ionian, Lydian, and Mixolydian, each of which has major 3rds.

Each mode has characteristic notes—particular notes that clearly set each apart from the regular major, or Ionian, scale. For example, notice that the 4th degree of the Lydian scale is a half step higher than its counterpart in the Ionian or major scale, and the 7th degree of the Mixolydian scale is a half step lower.

When we talk about what key a piece of music is in, we often describe both the tonality (the tonic pitch), and the modality (the type of scale on that pitch). For example, “A minor” tells us the tonic pitch is “A” and the type of scale is “minor.” Using the same terminology, if we say a piece of music is in “G Mixolydian,” we are saying that the tonic pitch is “G” and the type of scale based on G is “Mixolydian.”

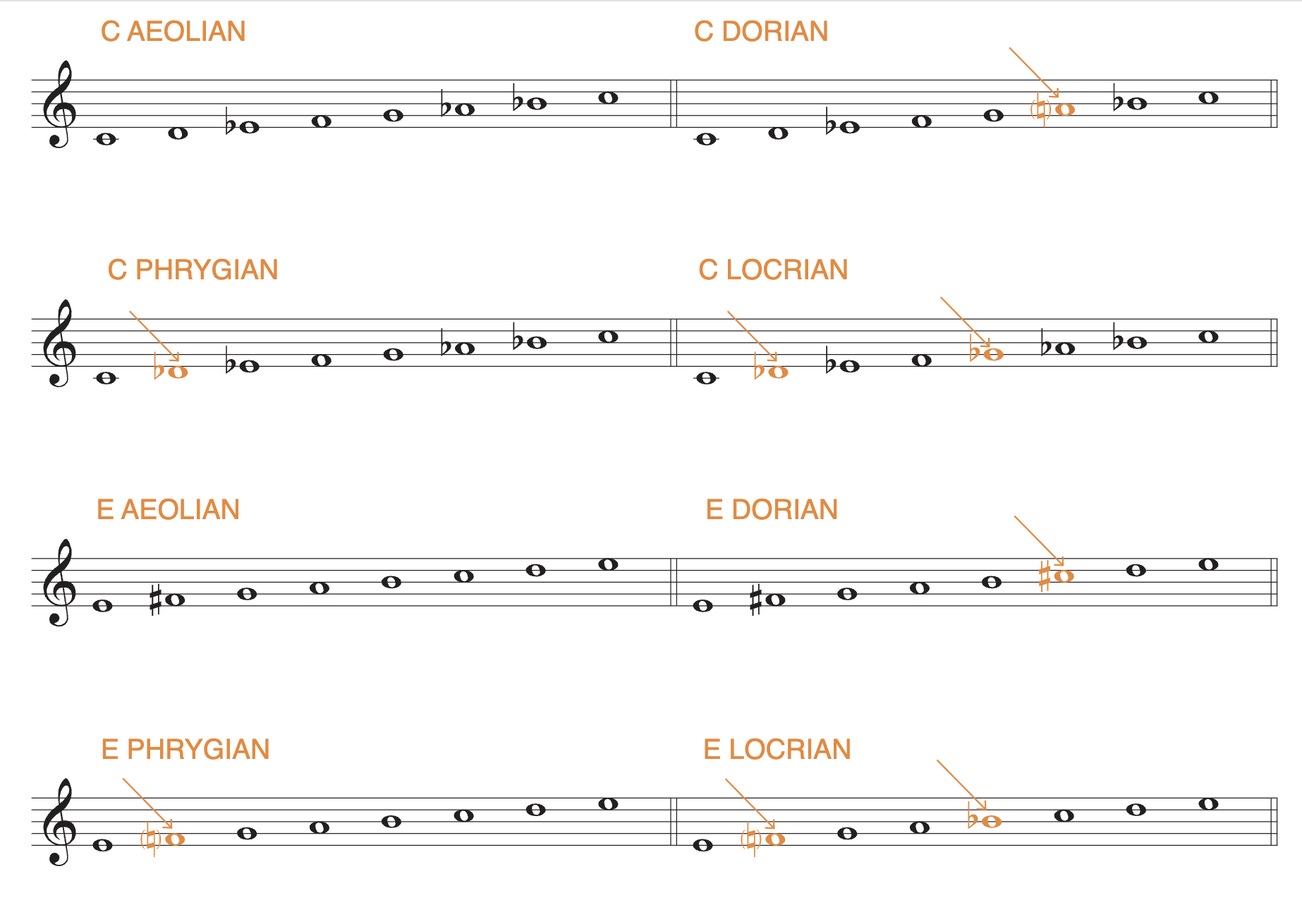

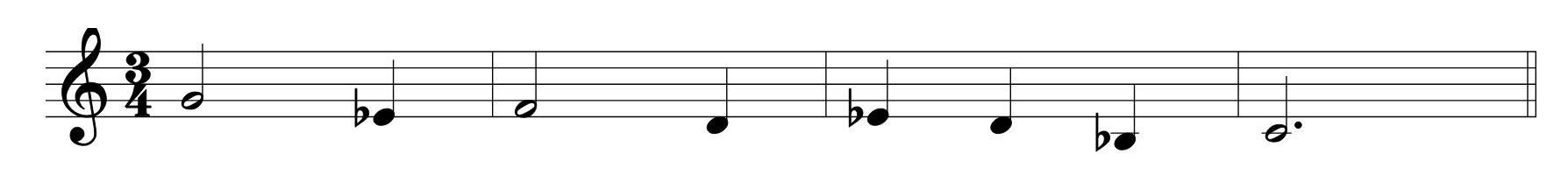

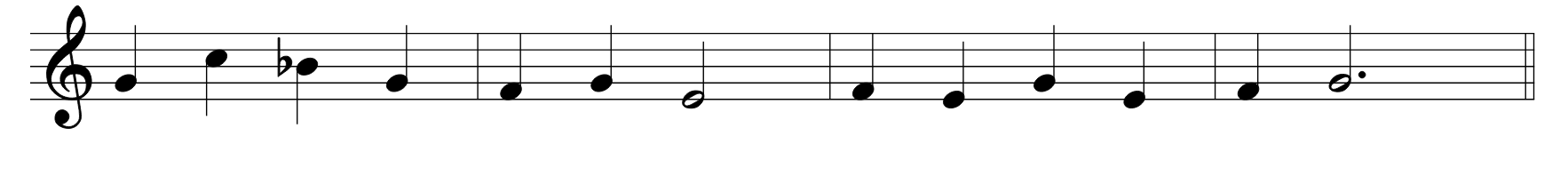

Here is a simple melody in the key of C major. Listen to how its character changes as it is “adjusted” to become first a Mixolydian, then a Lydian melody.

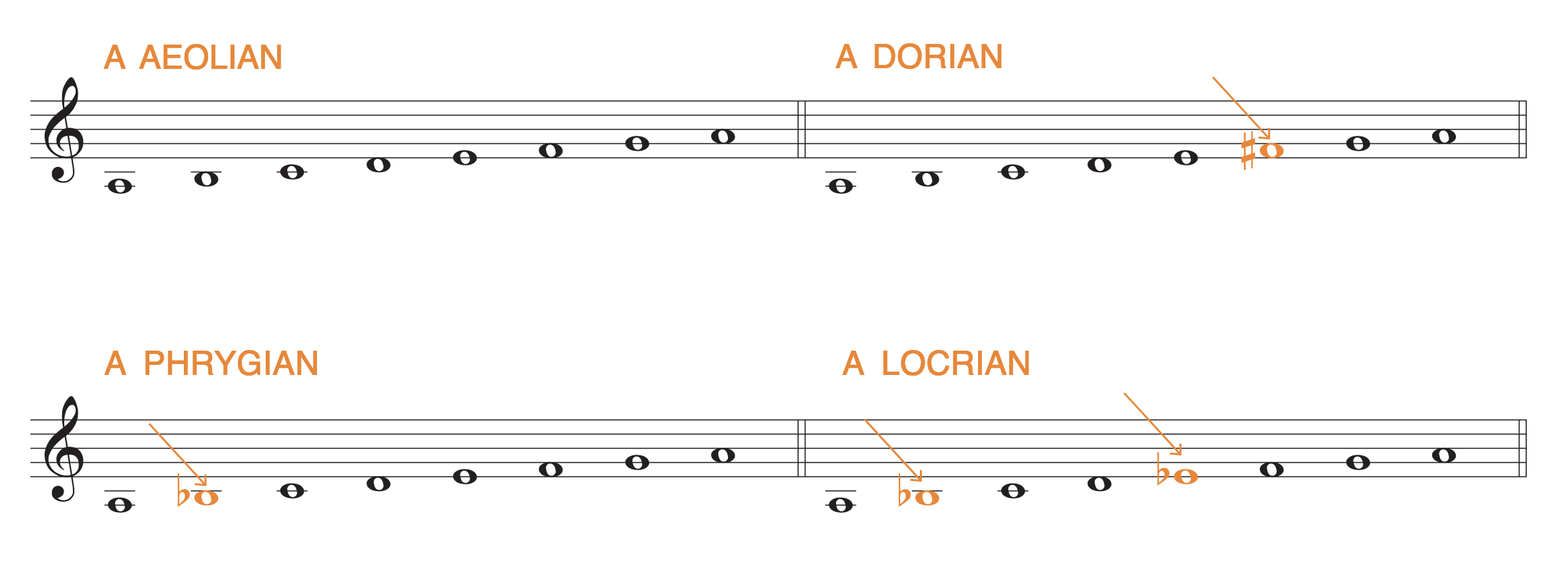

Minor Modes: Aeolian, Dorian, Phrygian, and Locrian

There are four minor modes (those with minor 3rds), and we have already seen one of them, Aeolian. Since we are familiar with Aeolian—we know the scale by its other name, natural minor —we will use it as a point of reference. The following contrasts the Aeolian scale with the other three minor modes: Dorian, Phrygian, and Locrian.

Notice that the Dorian scale has a 6th degree a half step higher than that found in Aeolian; the Phrygian scale has a 2nd degree a half step lower; and the Locrian scale has not only the lowered second degree but a lowered 5th degree, as well. These notes characterize the sound of these music modes, setting them apart from “regular minor.”

Let’s look at these minor modes on two other tonics—C and E.

Let’s revisit our melody and see how it sounds, first of all adjusted to Aeolian as written, then as Dorian, Phrygian, and Locrian.

Notice that Dorian sounds brighter than Aeolian, but Phrygian and especially Locrian have a much darker sound quality.

Writing Modal Melodies

Because our ears are more accustomed to hearing melodies in major, and to a lesser extent, “regular” minor, modal melodies have to work extra hard to promote their tonality and modality. Here are some points to keep in mind:

1. Make use of all of the notes of the scale.

In the following melody, scale degree 6 is not used, making it impossible to know if Dorian or Aeolian.

2. Make frequent use of the characteristic note of the scale.

This melody could stand a few more F♯s to ensure a Lydian sound.

3. Emphasize the tonic note.

Emphasize the tonic note by using it frequently and for notes of longer duration, especially those on strong beats. Assuming this melody is supposed to be in C Mixolydian, it needs more C notes—especially those of longer duration and falling on strong beats.

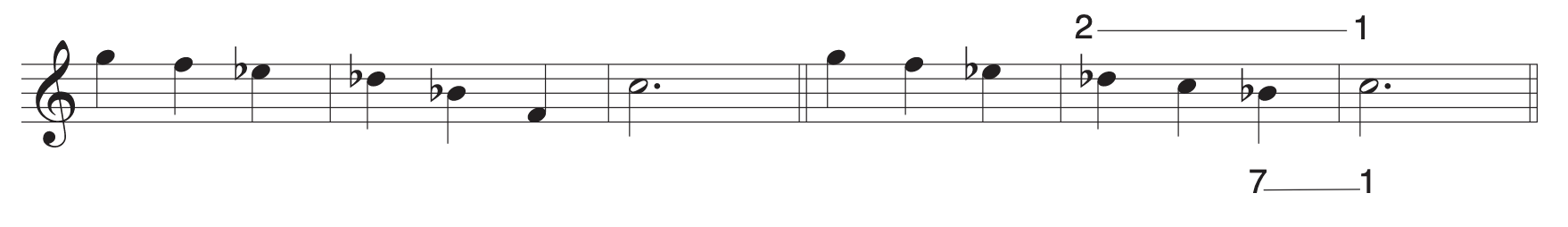

4. Use a “melodic cadence.”

Use a “melodic cadence” of scale degrees 2 to 1 and/or 7 to 1 at the end of each of your four-measure melodies. Melodic cadences, like harmonic cadences, resolve more strongly toward the tonic pitch than other scale members, helping to give the tonic greater emphasis. Notice in the following example that the sense of rest (cadence) is much stronger on C, in the example below.

5. Avoid leaping or spanning the interval of an augmented 4th or diminished 5th.

Avoid leaping or spanning the interval of a +4th or o5th, which occurs within each modal scale. This is an unstable interval with a strong tendency to resolve—but not to a place that we want it to go! It implies the dominant 7 of the relative major (the major scale with the same notes), and we do not want to go there. In the following C Dorian example, the interval E♭ to A, whether leaped or spanned, implies an F7, the dominant of B♭ major, and we do not want B as the tonic; we want C.

STUDY MUSIC THEORY WITH BERKLEE ONLINE

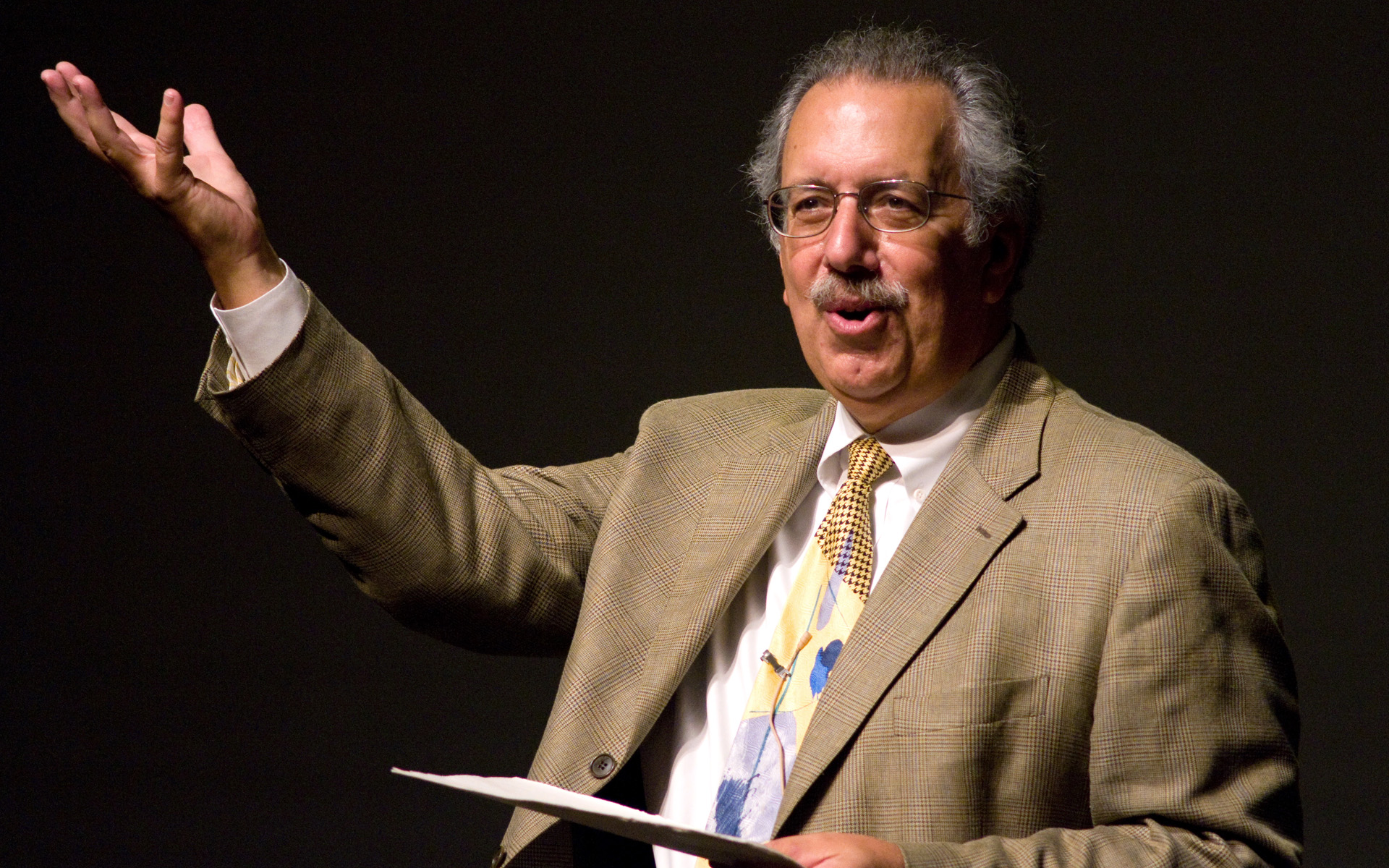

About Paul Schmeling 1938-2024

Paul Schmeling was the chair of Berklee’s piano department for 40 years. He began his career with Berklee in 1961: He was asked to join the faculty while he was still a student! He was also a pioneer in distance learning and online music education. He taught the Berklee Correspondence Course in the 1970s, and in 2002 he developed Berklee Online’s first ever online course: Music Theory 101.

Last year he spoke about what it was like to adapt the curriculum he had taught for decades for the online platform. He said he initially “overshot the mark” when he developed Music Theory 101, and tried to include too much information, which eventually led him to develop two additional music theory courses for Berklee Online.

“I had in mind from the very get-go what I wanted to see included in a music theory course, and there was nothing like it in the regular Berklee on-campus experience,” he said. “At the time, I was thinking it would be great if every student who came to Berklee knew this stuff before they started.”

In 23 years, Paul’s online courses have reached more than 15,000 students from around the world. He rarely missed a semester of teaching, sometimes logging in from cruise ships and remote vacation spots throughout his retirement. Paul was actively teaching Berklee Online students until just two months before his death in February of 2024.