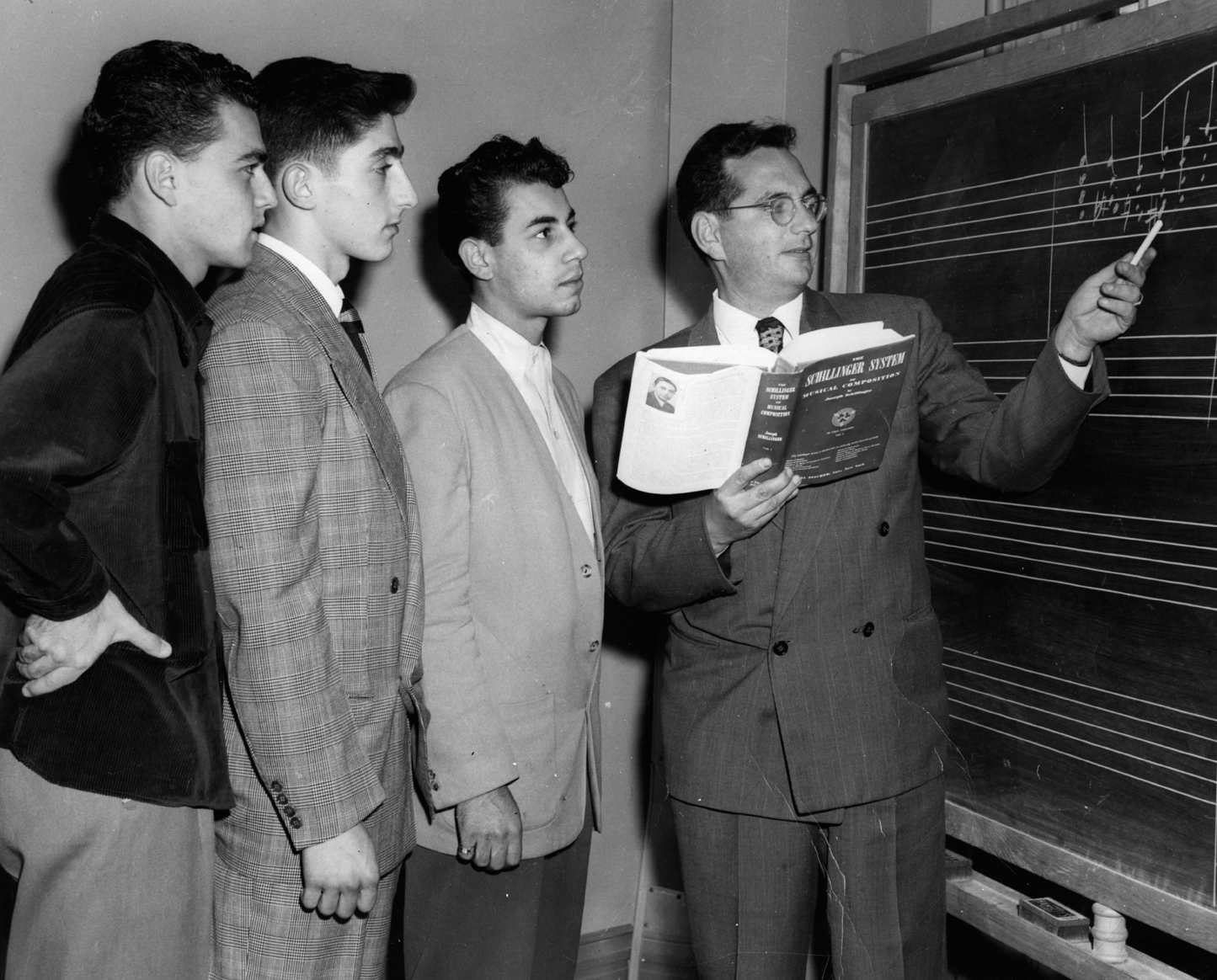

Lawrence Berk—the founder of Berklee, and my father (pictured above, far right)—was a jazz pianist, composer, and arranger. He acquired his craft skills with difficulty, when there was no organized system of education for jazz, which was the popular music of the time. He was heard to recall that fellow aspiring jazz musicians of his era had to resort to notating what they heard in recordings in order to study the compositional techniques they could use for their own musical needs.

Little wonder, then, as Lawrence Berk organized his subsequent career as a jazz educator, that one of his early projects was to launch a publishing activity, initiated in 1957 with a series of jazz recordings and score sets for professional musicians and other educators. Called Jazz in the Classroom, these LP/score sets were tributes to acclaimed jazz composers such as Duke Ellington, Manny Albam, Oliver Nelson, Benny Golson, and others.

Their music was performed at a high level by the accomplished students of the then-infant Berklee—often musicians from the armed-service bands returned from the war who were studying under the G.I. Bill or talented area players who were also then students, such as jazz trumpeter Herb Pomeroy, pianist Ray Santisi, drummer Alan Dawson, and others who would later become core faculty of Berklee for decades.

But for those who could benefit from these recording projects, there were many more who did not have any tools at their disposal to begin composing jazz or the ability to relocate to Boston for jazz studies. And so, Lawrence Berk began the Berklee Correspondence Course program.

It was a series of 25 lessons that led students through basic concepts of jazz theory, harmony, etc., all the way through to big band composing and arranging techniques. In what was little bigger than a basement closet at 284 Newbury Street (Berklee’s first home, pictured below), a single mimeograph machine operator, Robert Seastrom, produced these multiple page sets of information and exercises.

Registrants were mailed a single lesson set to study and complete. When the exercises were returned with a $5 fee, they were corrected by such early Berklee figures as Robert Share, Dean Earl, Harry Smith, Lillian Lee, and others, and the exercises with corrections and comments were returned with the next lesson set.

Over time, the vision broadened of what could be accomplished for the purpose of expanding music education through supporting faculty authorship. Notable early efforts were a series of saxophone studies by Woodwind Department Chair Joseph E. Viola and a series of guitar studies and guitar ensembles by Guitar Department Chair William G. Leavitt. Improvisation studies were authored by John LaPorta. Also represented at an early stage were saxophonist Andy McGhee, brass chair Ray Kotwica, and composer Ted Pease who did an audio/visual publication on jazz/rock theory.

In a departure from pure music studies, I myself authored a book on legal protection for musicians, which won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for Best Book in Music in 1971. It was later credited with stimulating the establishment of the Berklee major in music business/management. As both faculty and non-faculty authors added titles, it was often the case that a department chair was responsible for guidance and approving works eligible for publication. Most of these publications were produced in facilities expanded considerably from the original single mimeograph that gave birth to the correspondence course.

The print shop was run by Bud Mardin, and graphic artist Jon Lodge prepared cover and promotional art. As interest and demand in Berklee Press titles increased, a relationship was established initially with G. Schirmer and then with the Hal Leonard Corp., which in addition to its own titles, represented many other publishers. This relationship with Hal Leonard Corp. continues today, with them serving as Berklee Press’s distribution and marketing partner.

Ultimately, as technology provided the ability for online studies, Berklee provided the means to assist faculty in what was needed to present their coursework in the digital domain, via both Berklee Press ebooks (such as Kindle, Nook, and iBooks) and also Berklee Online, which is likely how you’re reading this article right now. The face of Berklee authorship became more complex, but the mission begun by founder Lawrence Berk remains the same: to expand music education opportunity by providing the information and tools needed for aspiring musicians to live their dream of a professional life in music.