The following information on melodic shapes in music arranging is excerpted from the Berklee Online course Arranging: Woodwinds and Strings, written by Jerry Gates, and currently enrolling.

As a composer, I’ve become a firm believer in the value of spending time thinking about what I want to musically say before I try to say it (write the pitches). This can save a great deal of time during the writing process by keeping me focused on my main point.

If a client asks you to write a theme that suggests adventure, where would you start? What kind of a melody could represent adventure? What kind of a melody wouldn’t represent adventure? There are conceptual ideas we can explore to help us narrow down our choices—that of melodic shape. In other words, if we figure out what type of melodic shape sounds the most adventurous, from a conceptual point of view, then it will be much easier to write the actual notes that fit that idea.

The pitches themselves won’t really matter as much, because the shape of

the line will determine whether we are suggesting adventure or not. There are three fundamental shapes that melodies contain. All three shapes are not necessarily contained in one melody, but aspects, or parts, of these shapes are.

Melodic Shape: Line

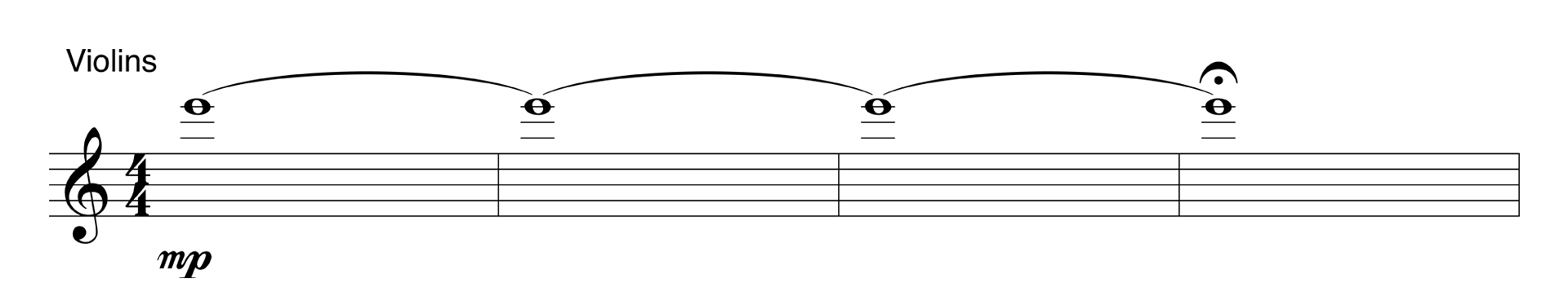

The main characteristics of this shape are repeated notes or notes held for a long period of time, as in a pedal point high above or below the staff. An ostinato also falls into this shape classification. As the group of notes repeats itself over and over, a “line” shape is formed. The example below illustrates a line shape. Note that there are many repeated notes, particularly at the beginning of each measure. When playing or singing this example, does it seem like the melody is a complete thought, or do you want something else to happen?

The next example is what is often called a “wire.” I’m sure you’ve heard this technique used in many films. As the question was posed in the previous paragraph, is this a complete idea? Are we satisfied, or do we want something else to happen, musically?

In the example below, I have composed a simple two-measure phrase that repeats over and over. If this continues over a period of time, will it be enough of a statement for us, or do we want something else to happen as well?

The three examples above are all line shapes. After careful listening, we can come to the following emotional (or dramatic) responses:

- Line shapes aren’t complete thoughts in themselves. Rather, they “set up” action or musical movement to come.

- Line shapes are great for introductions to a main idea—they are not the main idea themselves.

- Over a period of time, line shapes (as in an ostinato) will fade into the background, as the repetitiveness will let the brain register that idea, and then focus on other melodic ideas as they are introduced.

One other thought about line shapes: If long tones are added to syncopation

(very rhythmic music), the long tones will take the edge off the syncopation, making it less forceful. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing; it’s just another textural choice. There are many examples of this in funk music where the bass, drums, percussion, and horn lines can be very rhythmic, but there is also a keyboard playing long tones called “pads” (often string or brass sounds) that in a very real sense “glue” the sound together. Again, the long tones (pads) take the edge off of the overall forcefulness of the rhythm. There are examples of this in orchestral literature. One that comes to mind right away is the introduction to the Ralph Vaughan Williams piece entitled, “The Lark Ascending.”

In the introduction to this composition, a solo violin plays a fairly rhythmic

cadenza or solo section. While this is occurring, the rest of the string section is playing long tones (literally tied whole notes) using an E Minor Add 9 chord for what seems like a very long time. The held notes in the strings add glue or harmonic support to the cadenza. It also takes the edge off the rhythm of the cadenza. Also interesting in this piece is that at about the halfway point of the introduction (1:12), the held notes go away completely so that just the violin soloist is playing the cadenza—no other instruments are sounding. When this happens, what is the effect? Does it feel like the harmonic pad is still there (or at least the effect of it)?

Wire in Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “A Felicidade”

This next example is an illustration of how I used a wire (high pedal point)

in the strings, and a solo trombone playing a melody against it. Its use is

as an introduction to a music arrangement I wrote to Jobim’s “A Felicidade.” Note how the initial wire in the strings presents the emotional need to hear more, as it doesn’t seem to go anywhere. On cue, the solo trombone answers that request while focusing the attention on the soloist. Once the trombone enters, the wire now serves the purpose of holding the music in one place. Eventually, on cue, the additional woodwinds, strings, and rhythm section enter. Their movement, and the dissipation of the pedal point, creates motion in the music and allows the music to move forward.

On cue, the solo trombone answers that request while focusing the attention on the soloist. Once the trombone enters, the wire now serves the purpose of holding the music in one place. Eventually, on cue, the additional woodwinds, strings, and rhythm section enter. Their movement, and the dissipation of the pedal point, creates motion in the music and allows the music to move forward.

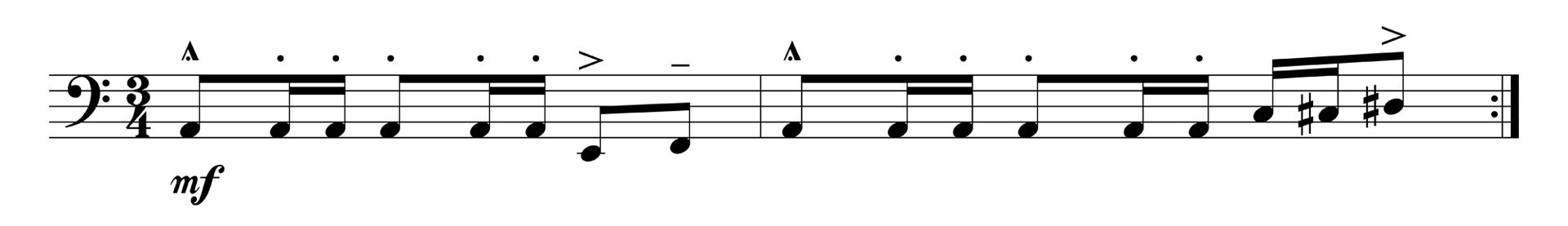

Melodic Line Shape of “The Taking of the Pelham 123”

There is another way in which we can use a line shape—as an ostinato or repeated phrase. Over a short period of time, the listener will be wondering, “what’s next?” as the repetition of the ostinato isn’t really a complete thought. In this case however, the ostinato does set up the groove and overall feeling of the music.

Melodic Shape: Circle

Imagine the shape of a circle. Note the smooth edges. To create a smooth sounding melody, we need to use a minimum of leaps. The majority of intervals used in a circle shape are half and whole steps. It is possible to mix in an interval larger than a half or whole step to this type of melodic idea, particularly at the end of the phrase, but the overriding idea must be small intervals. The next example illustrates a circle shape, and it is made up primarily of half- and whole-step intervals. The only exception is at the very end of the phrase. Dramatically speaking (emotionally), this type of shape “tells the story,” which is why a circle shape is used in so many verses.

The application of the aforementioned shape is all around us. It is easy to sing, due to the stepwise motion. Think of a popular song, or a church hymnal. The verses usually have a preponderance of stepwise motion—again, to make it easier for people to sing.

Here are a few great songs that have a circle shape for a verse (or sometimes a chorus/ bridge) section of the song:

- “Deck the Halls”

- “Night and Day”

- “Insensetez (How Insensitive)”

- “Venus”

Melodic Shape: Square

As opposed to line shapes (repetitive nature or long tones) or circle shapes (smooth, stepwise motion), square shapes have the element that is so far missing—intervallic leaps. The larger the leap, the seemingly more

dramatic the melodic line. Dramatically speaking, square shapes seem to

suggest adventure, despair, happiness, loneliness, and a host of other extreme feelings and emotions. Composers that write for dramatic purposes (film composers, for example), sometimes think about this type of melodic shape before the actual pitches are secure, or even known.

Learn about a music career as an arranger.

Combining Shapes

Film composer John Williams is a master at creating dramatic melodies.

In this next example I’m citing the basic melodic idea from “Princess Leia’s Theme,” from the movie Star Wars. You’ll notice that the intervals in this melody fall into two categories that we’ve discussed—square and circle. The square shape intervals are the leaps that are in the beginning of the phrases. First, a major sixth interval (measure 2), then another major sixth interval (measure 4), and finally in measure 6, an octave leap. The circle shape intervals are basically everything else, as most of the remaining intervals are whole or half steps up or down. The big leaps at the beginning of each phrase are what keys the ear into the overall feeling of the idea.

The three fundamental melodic shapes presented here are not often

seen as “note for note” one shape or another. As we’ve seen in the last two

examples, melodic lines are commonly a combination of shapes. What one looks for, however, is a melodic idea that suggests one shape over another.

If a melody has a great deal of stepwise motion, but a leap here and there

(particularly at the end of the phrase), then it will still be heard as a circle shape. The leaping intervals should not be placed near the beginning of the phrase where the ear first identifies it. Likewise, as in the first example from the beginning of the lesson, a series of repeated notes will be heard as a line shape, even when periodic intervals are present, because the leaping intervals are at the end of the phrase.

STUDY ARRANGING WITH BERKLEE ONLINE