To learn is to do. Let’s pretend that you want to become a marathon runner. First, you would identify that you liked to run and seemed to be pretty adept at it. Eventually, you would need to hire a trainer with the knowledge of how to build your body properly. Next, you would need a coach to help you prepare for each individual race. You, your trainer, and your coach would all work in tandem to help you reach your goal. All the while, what would be your primary activity? Running, doing. How long would this training, coaching, and doing go on? Well, this is the million dollar question.

Professional runners have coaches, trainers, and other hired help aiding them throughout their careers. Many casual runners seek professional help on a regular or an as-needed basis. No one in their right mind would attempt running a marathon without some guidance and rigorous training at a gym and in the field. There are varying levels of preparation and varying levels of dependency on outside help needed to guide people to their goals.

The keys are the setting of the goal and the doing, the action of going about attaining the goal. I call this doing gyo (a term I picked up from of an Eastern philosophy book, years ago). To me, gyo is conscious action, or doing, through guided force. It is taking the positive steps to gain through action. You might liken it to positive motivation. In so doing, it becomes easier to understand why some runners are so natural, such perennial winners, so awe-inspiring, so talented, so strong, so energetic, and so on. These runners possess gyo and know how to put it to good use. They have the knowledge of how to do. And so it is, as a performer. But it is not as easy as I have made it seem to be. It is true that all you need do is set your goal and go about attaining it, but so much happens in between.

STUDY BASS WITH BERKLEE ONLINE

Creating and Maintaining an Effective Practice Schedule

You teach yourself to read, you join a funk band, someone shows you how to slap, you get a gig, you get a double bass for free from your uncle, you buy a bow, you take lessons, and then… you quit. Well, you get the point. We all have dynamic lives that cannot be predicted. So how do we hold onto our goals? The answer is simple. It is not so important to hold onto goals as it is to have goals. People change, goals change. What is important is gyo! You will need to reevaluate, and oftentimes change your goals. It is the gyo that causes this. Think about all of your musician friends for a minute. Let’s put them into groups. Then you decide which group you fit into.

Beginners

Enough said. Beginners need to work on every aspect of their musicianship, and should have a well-rounded practice session, emphasizing technique, but also touch on ear training and musical development.

Street Players

These players are very adept at one or two styles, which they learned by listening intently to musicians they like or hanging with friends. They probably play casually a lot and might even have a gig. Street players would be well-served to develop their reading skills and to explore styles beyond what they usually play.

Technically Challenged Players

They can’t really play very well. Technically challenged players can’t seem to get the feel or the technique down. They just don’t understand what to do, but they love to play. Regular attention to technical studies, such as scales, arpeggios, and various fingerboard exercises will help technically challenged players improve their skills, as will a good teacher.

Forcers

Forcers sound like they are reading. When they play, you sometimes think you are listening to a machine. Practicing by ear, widening their use of articulations, and learning to improvise can help these players to develop a more human sound.

Jazzers

The jazzers possess natural talent. They can play almost anything that they hear and can fake their way through many situations, but they may be style-restricted. Jazzers should broaden their abilities to include other styles into their repertoire.

Rockers

Rockers are limited jazzers. They are often stylistically restricted. Rockers should also work to bring other styles into their repertoire.

Semi-Pros

Semi-pros are conscientious players who take or took lessons and try to cover all the bases. Semi-pros are everywhere. They need only conscientious work and time to develop their abilities.

Pros

The pros seem to do it all, with little or no effort and are paid well to do it. They are not necessarily prepared for any situation, but rather, are willing to prepare for any situation. Pros are committed to being the best and command respect from the rest. Their practice time can focus on learning more music and maintaining their chops.

Where Do You Fit In?

So, where do you fit in? Well, I have good news for you. You can fit in anywhere and still be successful. But it is important to see where you fit in. You must come to an understanding of where you are, if you are to have any chance at setting goals for your future. Armed with self-knowledge, a love for music (and of course, for bass playing), and the desire to improve, you can set some goals.

Take Time to Define Your Goals

Spend a week or so initially thinking about what your goals might be. Jot down the ideas that come back again and again. Look over your ideas, think about your spot on the list of types of players, consider your age, and consider your time constraints. Be honest with yourself, and evaluate your present state of motivation. With all of this evaluating, you will gain a deeper self-knowledge, which will point in positive directions. A goal or several goals will become clear in time. Then, you must commit to your goals. It is at this point that the gyo takes over.

Gyo and “Directed Doing”

After identifying goals, you must go about attaining them. We already know that this is through doing, but the doing must be directed. Unguided doing is chaos and can only lead to random results, at best. As with the runner, the musician often seeks help from others more versed in the craft. Much knowledge and a clearer picture of oneself can be gained through a relationship with an instructor. I can’t tell you how to find an instructor, but I can suggest some of the attributes that a qualified instructor will have. Look for someone who exudes self-knowledge and confidence, someone playing all of the things that you want to play, someone able to communicate clearly. Find someone who is busy but can find time for you, someone who can motivate you, someone you can trust, someone with the patience of Job. Use your teacher, trust your teacher, and if you must, fire your teacher. For many, the teacher/student relationship lasts a lifetime. Search until you find your teacher. Your studies may require weekly lessons. Many teachers have the need to set up a regular schedule, and a regular schedule is usually the best regime for the student. Some prefer biweekly or monthly meetings.

Be Prepared… To Compromise

Some sacrifices may need to be made to secure your lesson time. I was once on a waiting list for two years, hoping to study with Charlie Banacos, a noted music guru in the Boston area. When he finally called me with an opening, it was for 7:30 AM every Saturday! Needless to say, I made some major adjustments to be prepared for his guidance each Saturday morning. In time, you may have lessons only as needed. This relationship will be malleable and ever-changing, but always guided by the teacher with the student’s growth in mind.

Learn How to Practice

So, you like playing the bass, you have done some soul searching, and you know where you are. You have taken the time to consider setting musical goals, and you have come to know that study, possibly through a teacher, will help you attain your goal. It’s about time you learned how to practice. You know what they say, “practice makes perfect.” I don’t know if it’s true or not, but it sure can help. Consider how valuable your time is, and realize that you will be investing your time into your practice. Don’t waste your time, value it. When you realize that your practice time is a major means of attaining your goals, it becomes clear how important this time is. Your practice time must be planned, dynamic, and regular to be most effective. Haphazard practice does achieve results, but never of the magnitude attainable through the rigors and discipline of regular, intense practice. The specific content and duration of your practice will be determined by your individual circumstances. Your teacher can be a great aid in determining these factors.

Learn to “Need to” Practice

There are some general guidelines that will help you create and maintain a good practice schedule. Humans are creatures of habit, living in a world that repeats itself every day. With this said, the most important aspect about your practice schedule is that it needs to be regular—preferably, daily. You will achieve the best results if you can integrate your practice schedule into your daily life. In so doing, you can actually cause yourself to “need to practice,” which is a great help for those of us without optimum motivation. One could go further and consider practicing every day at the same time. For some, this is the optimum, but others need be careful of burnout or getting into a rut. Self-knowledge and a sense of human nature are the keys to getting yourself on track to a successful practice schedule. Always consider your ultimate goal, but now, be ready to set interim, short-term goals that will ultimately lead you to your final goal. Reevaluate every six months or so to be sure you are still on track or to decide whether you need to adjust or change your track.

To help create a “need to practice,” start off by not allowing yourself enough time to accomplish all of your tasks. Stay focused and work hard. Don’t waste time. You will realize that you need more time to finish your work. After a short while, you should add time, as needed. Never alter your practice habits drastically, all at once, as this will cause chaos within your musical anatomy.

The Three Areas of Practice

I have heard of players utilizing practice times from ten minutes to ten hours per day, achieving success at each end of the scale. Of course, success is also a relative term. One practicing ten minutes a day cannot expect to make great leaps in their abilities from week to week. On the other hand, one practicing ten hours a day may need to get a life. Or maybe, they have found one. Performing regularly on gigs, or just playing in a garage band, can restrict the amount of your practice time. For most players, the exertion of “real” playing far surpasses the strains attained in the practice room. Performers with day gigs that tax the muscles of their musical anatomy, or players participating in sporting events that use these muscles, need to be mindful of their bodies’ physical limits. They may also need to restrict their practice time. A practice routine is an exercise program with academic material incorporated into it. As such, I again recommend that the player seek out a competent instructor with whom to work out the physical and mental dilemmas related to playing bass. The specific choices of exercises and the incorporation of academic material can be individualized by the performer (student) and the teacher. There are, however, three areas that practice material can be classified. All are equally necessary for successful practice.

-

Maintain and Build

Each player comes into this with certain physical and mental ability. As long as we have proper physical technique and our academic foundation is not flawed, we must first maintain our current level, and in time, we need to build upon it. Specific fingering exercises, scale and arpeggio patterns, and stamina exercises are often used for this purpose. Occasionally playing or reading pieces previously mastered can also help to fulfill this area of practice.

-

Personal Interests and Needs

All players have tunes that they want to learn. Many of these can be quite difficult to learn and play. This type of material needs to be incorporated into the practice schedule. Learning can be accomplished through reading or transcribing. In learning a piece that you’re often listening to on the stereo or headphones, take the time to transcribe the music on paper first. This action will help you learn the piece more quickly, help to locate errors, and help to improve your reading ability. You don’t always love what you have to play, but since you love playing bass, you play whatever you need to play. Many players feel this way, and so, there arises a need to incorporate material that you love into your practice time. Choose material that has personal meaning to you. This type of practice can be particularly enjoyable.

-

Survival Skills

There are sometimes things that must be learned in order to survive. You are playing a show next week, and the part is too difficult for you to sight-read. You just joined a band, your first gig is this Saturday, and you need to learn eighteen tunes from a demo. You have an audition with an orchestra next week, and they are going to have you play excerpts from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. These are all examples of needs for your immediate survival as a bass player. Not only does this material need to be incorporated into your practice schedule; at times, this material will supersede all other. In the end, it is a blend of these that you should strive for, leaning, at times, in one direction or the other, depending on which direction the wind blows.

Allot… A Lot!

Strettttttch!

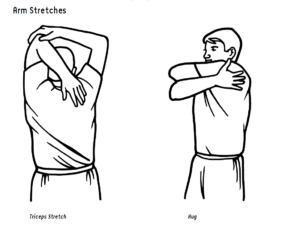

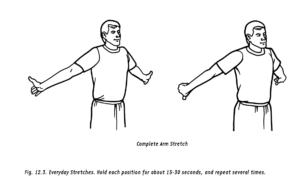

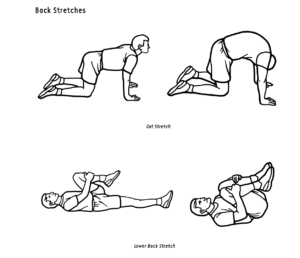

Most practice should start with stretching. It is not good to play or stretch, seriously, when cold. If you are cold, play lightly to bring your muscles up to a warmer, more comfortable temperature. When your fingers are at a comfortable temperature, you are ready to begin your stretching. This initial stretching is not meant to be serious, drawn-out stretching, but is intended to loosen up and prepare your musical anatomy for what is to come. All of the areas used during performance should be stretched before any serious practicing is attempted. Many players have “weak spots” or problem areas that they may give some special attention to. Many players don’t feel the need to stretch. If they are lucky enough to still be performing in twenty years, they will have changed their minds, and in fact, may need the stretch more than the rest of us, after not stretching for twenty years. Refer to the pictures below for some useful stretches.

After a moderate stretching period, time should be devoted to warming up. Your muscles need to warm up further to function at optimum. This is especially true in colder climates. Find some slow, easy material to use. Repetitive material that uses all of the fingers equally and works all of the arm, shoulder, and back muscles to some degree is good. Some players like to work in some sight-reading at this point.

These two areas of stretching and warming up can be mixed or reversed to some degree as your physical needs and temperatures dictate. If you are a particularly cold-blooded person, or during winter months, it is best to warm up some and then stretch, possibly completing the warm-up after stretching. Muscles do not properly stretch if cold, and stretching cold muscles can cause injury. Stretching should never be painful. If it is, you are going too far.

The first centerpiece of your practice regimen should be skills practice—the scales, arpeggios, melodic patterns, chord progressions, and the like, that constitute the foundation of our bass playing. Much of this material will be suggested by your teacher. This practice needs to be intense and ever improving. Additions and subtractions to the materials should be made from time to time. This is mental as well as physical practice, and for most players, it is quite dynamic and fluid.

As your practice time increases, and especially if you are not playing gigs on a regular basis, you should incorporate the second centerpiece: gig situation-playing. You must put yourself in the mind of a performer on a gig and play on. This must be as intense as the gigs you can imagine. Concentration is the key to this type of practice, as you could play an entire set of jazz standards or a Mahler symphony from start to finish. No stopping is allowed. Treat this like the real thing. If you have the time for more than one set, take a break and do it again. Gig situation-playing is also both mental and physical. It is intended to build physical stamina and concentration.

The Cool Down

When your time is becoming short, go to the cool down. It is just the opposite of the warm-up. Relax a little, play something simple, let your mind begin to wander. This can also be a good time to bring yourself back to Earth mentally, and practice a little reading. Just before you are finished, stretch again. This stretching should be more strenuous than before, since your muscles will be quite warm. Your muscles will stretch quite easily. Hold your stretches for about thirty seconds, if possible. You will find your flexibility will improve from this stretching, and the possibility of injury will decrease. Stretching should never be painful.

Practice is hard work. It consists of physical exertion and guided thinking. It must be this way if you want it to work for you. On the other hand, you may have occasionally experienced wonderful personal performances when you seemingly had no thoughts. This is the balance of the world of opposites in action. There exists thought and no thought. Neither can exist without the other, and each is dependent upon the other. Our ultimate objective is to exercise thought during practice and no thought during performance. This is a difficult ideal to obtain, but the knowledge of its existence helps us to achieve it. Now, all you have to do is fill in the blanks for your own practice schedule.

Keep Your Heart Healthy

To keep yourself in top shape, I also recommend regular non-musical exercise. I’m talking about swimming, running, playing soccer, going to the gym, biking—you get the idea. Bass playing doesn’t do a lot for the physical health of our hearts. In fact, the bars, clubs, practice rooms, and restaurants we find ourselves in can actually cause damage to our hearts, and there is nothing worse than a bass player with a damaged heart. Consider getting yourself into some regular activities that promote the well being of your heart. Join a soccer team, buy a bike, or my best idea, join the YMCA or another full service gym. All bassists need to develop an approach to warming up, or preparing their performance anatomy for action. Casual players may not see the need to warm up, due to the fact that they may not presently be taxing their muscles. But as they age, or as performance opportunities become more intense, physical warm-up will become a necessity. Professional players must be at the top of their game at all times, and a methodical warm-up is generally the manner in which they begin a performance or practice.

This need to warm up has the added advantage of forcing you to get to the gig early, helping you avoid being docked or fired, as many latecomers are. Warm-up exercises should have a purpose, or two. Warm-ups need not be difficult; in fact, they should be simple in nature and should not cause stress. Speed is not a factor. Most warm-ups are best performed at slow to medium tempi. Effective warm-up exercises use all of your physical performance anatomy in relatively equal amounts, preparing all parts to function efficiently in performance. Players need to design warm-up programs that suit their performance requirements. Warm-up programs may differ from day to day, depending on the player’s immediate needs. There are a number of benefits to be gained from proper warming up.

Personal Preparation

Your muscles function best at around 103 degrees. You may have a gig in Hartford on February 10. After dragging all of your gear into the club, setting up, and pulling out your bass, you might notice that your fingers are still cold, real cold. Might I suggest a little warming up before the first set? This may be an extreme case, but even muscles that are just slightly chilled can be seriously injured by strenuous work. Don’t forget that your fingers are an extremity on your body, and as such, are cooler than your central body. It is a good idea to lightly warm up even on a warm day. Remember that your body temperature is below the 103 degrees that your muscles like for performance, so the warm-up prepares your muscles for the work to come. The warm-up needs to establish good blood circulation, warm the muscles, and warm the flesh so that the sense of touch feels comfortable. Once all of these needs are met, you are ready to perform.

Excerpted from The Bass Player’s Handbook, by Greg Mooter (Berklee Press).