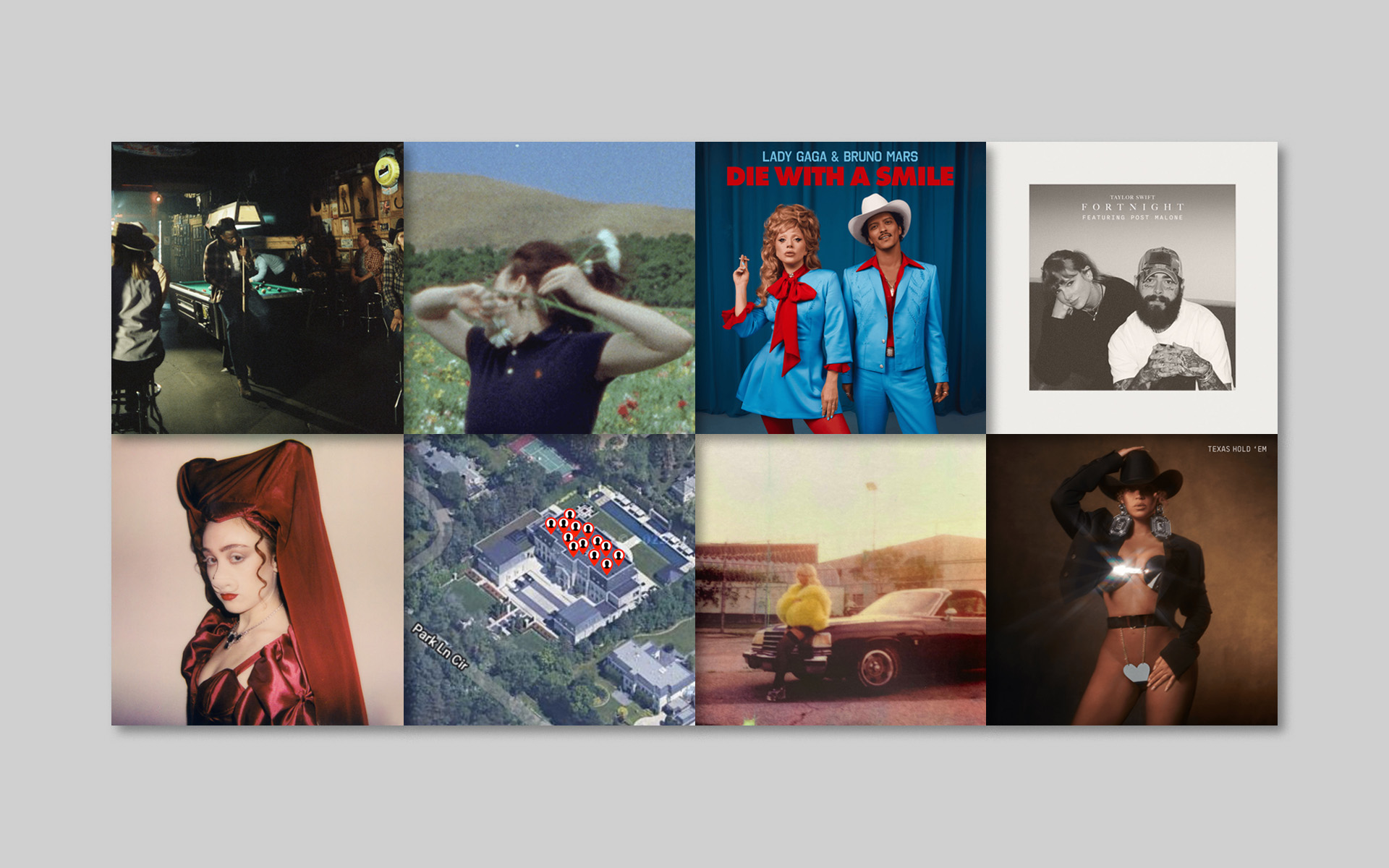

Key changes can inject any song with an exciting (and often unexpected) jolt of interest, but as you’ll see from the article below—assembled with the help of several Berklee Online instructors in the Songwriting and Music Production departments—it takes a special skill to really make modulation work. The 29 songs that are part of the embedded playlist below (and the more comprehensive write-ups after) not only showcase the skills of the songwriters, but also the talents of the singers who make the big leap into a new key. And one note of caution: Modulation should be used in moderation, unless of course you’re in Queen or you’re the Queen Bey.

“Love On Top” by Beyoncé

Songwriters: Beyoncé Knowles, Terius Nash, and Shea Taylor

We’re putting “Love on Top” on top of this list not just because it has the word “top” in the title, but because of its impressive four key changes. Released in 2011 on Beyoncé’s fourth album—appropriately titled 4—the song begins in the key of C. After two verses and two choruses it jumps to C♯ for a double-chorus at approximately 3:04. Then it keeps moving up! The second key change modulates to D at approximately 3:24. Then it modulates to E♭ with the word “top” in the chorus at approximately 3:45. The fourth and final key change happens at this same point in the song structure, with the next leap on “top” to E happening at approximately 4:06.

If you can’t tell where the key changes are happening and you don’t feel like following along with the time codes, just watch the video. Each time the outfits on Beyoncé and her dancers change, so does the key! The live version of this song on the Homecoming album (documenting her tour de force performance at Coachella in 2018) begins in B♭ and climbs up to D. What’s noteworthy about this is that she brings the entire crowd on up to the notes with her!

“The first time I heard ‘Love On Top,’ my pupils dilated with the delight of each new modulation,” says Ben Camp, who wrote Berklee Online’s Songs Unmasked: Techniques and Tips for Songwriting Success course. “At some point I was like ‘They’ve gotta be done, they can’t modulate any more!’ and then they. kept. doing. it. So good!”

Rodney Alejandro, who wrote Berklee Online’s Topline and Vocal Production course, calls the song “a modern classic.”

“It utilizes key changes to highlight prosody in the song, arrangement, production, and performance,” he says. Plus, “it feels great to groove and move to!”

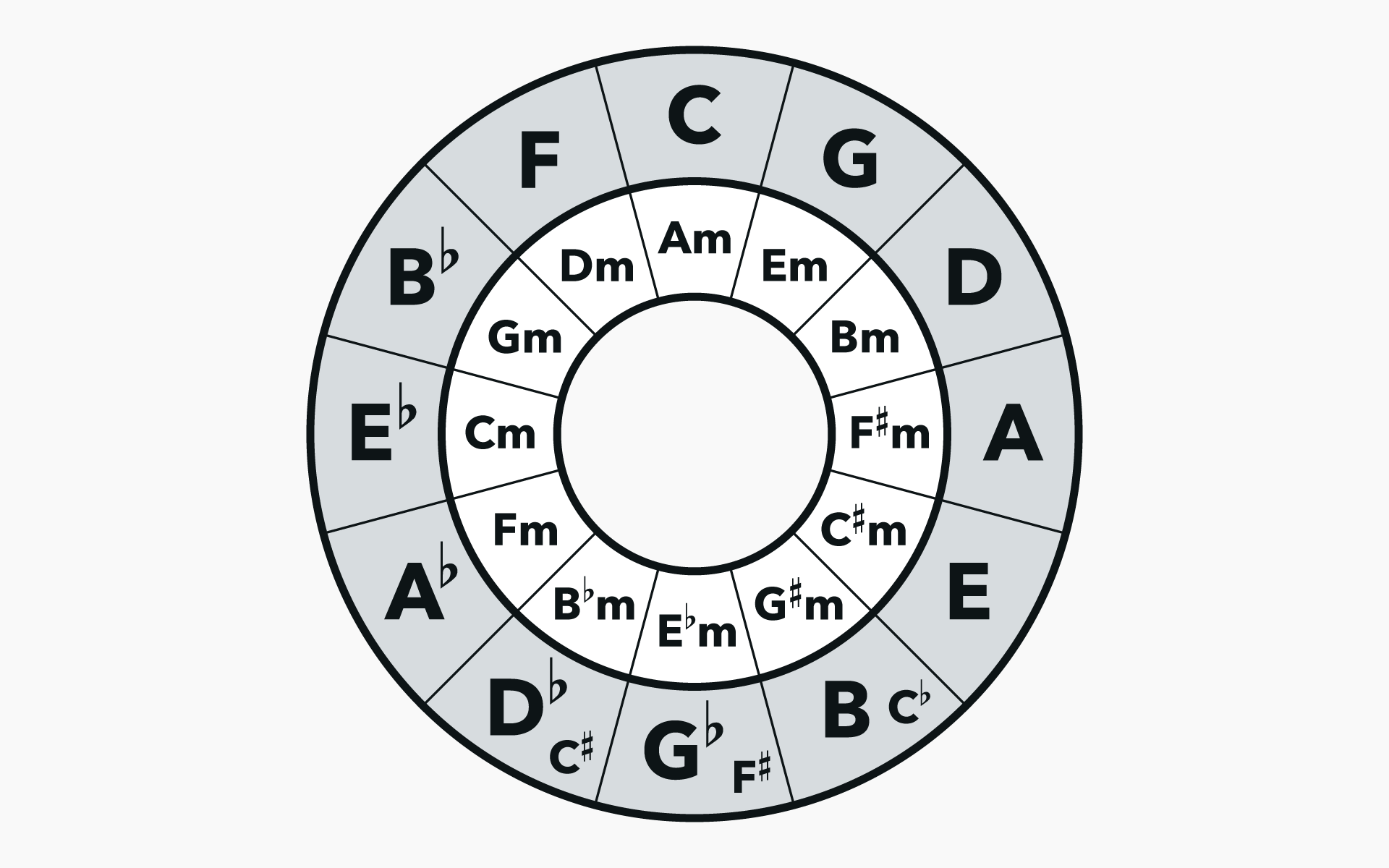

What is Modulation?

Modulation is when a song is in a certain key and it moves to another key.

What is the Purpose of Modulation?

Usually to add excitement to the song.

What are the Three Types of Modulation?

- Diatonic

- Chromatic

- Enharmonic

Check out this article from Berklee Today, a publication from the campus of Berklee College of Music, for more info.

“Man in the Mirror” by Michael Jackson

Songwriters: Glen Ballard and Siedah Garrett

This 1988 hit from Michael Jackson is notable in that it uses prosody when it modulates. As a refresher, prosody can mean an instance when the music reflects what the words are saying: One classic example is Garth Brooks singing a low note when he says the word “low” in the chorus of “Friends in Low Places.” Accordingly, the members of the Andraé Crouch Choir sing the word “change” as they make that leap up from a G to an A♭ major. When we hear these singers “make that change” at 2:53, it gives us listeners the feeling of possibility that we can help “make the world a better place” in a song that has already been an uplifting experience.

“If you listen to the song, it starts with realizing that if anything is going to change, it has to start with the singer,” says Chad Shank, who teaches Lyric Writing. “The song builds from this starting point in energy. Not only does the song itself build in energy, but by the time the key change happens the production is rolling full-steam ahead. Then BOOM! It becomes gospel and such an uplifting, almost spiritual feeling. That the change happens on the word ‘change’ is just amazing prosody. We feel that. We feel the change actually and emotionally.”

Kelly Riley, who also teaches Lyric Writing, adds “just when you think Jackson’s electrifying, soulful delivery can’t get any better, the song lifts like a rocket.”

“This kind of upward shift in the tonality is a simple but visceral way to re-engage the listener,” observes Joe Mulholland, who teaches the Getting Inside Harmony 2 course for Berklee Online.

“I Will Always Love You” by Whitney Houston

Songwriter: Dolly Parton

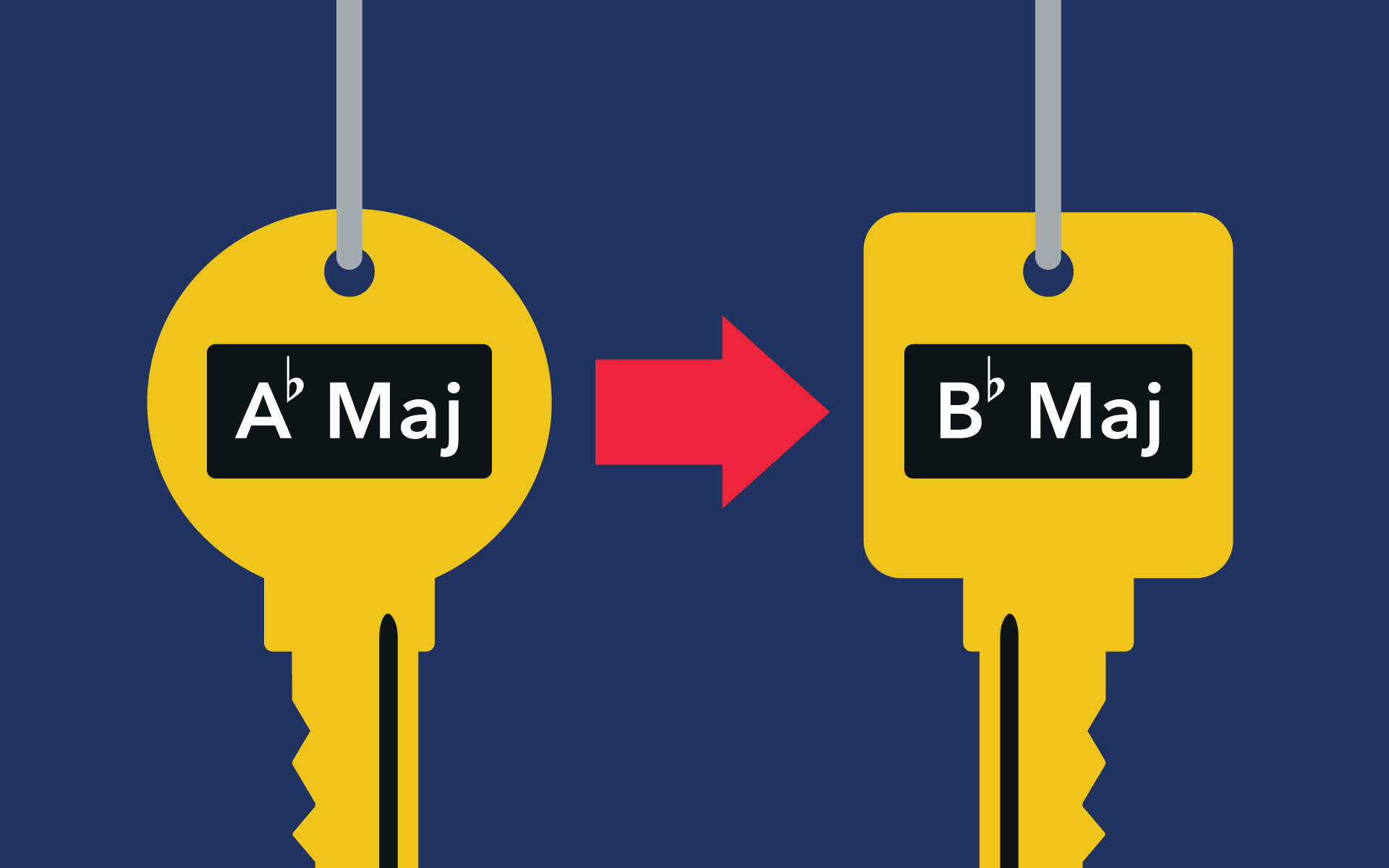

Let’s get this straight: The list is not a definitive ranking of songs with amazing key changes. We’re offering this disclaimer here because there are many days where we would rank this song from the 1992 soundtrack to The Bodyguard above the previous selections you’ve already read about. The sheer power of this key change—a full step up from A♭ major to B♭ major—practically shifts everything inside the listeners’ souls in the same way that it shifts the notes that the musicians can use. The magic of this modulation, which occurs at approximately 3:06, is that Whitney’s voice is the instrument that leads the band to a higher key. As all other instruments drop out and one reverb-drenched drum signals the change, Whitney comes in, packing a heightened emotional charge.

Dolly Parton—who wrote the song (on the same day that she wrote her classic, “Jolene”!)—recorded “I Will Always Love You” three times; originally in 1973; again in 1982; and in 1995 as a duet with Vince Gill. In this final version she employed a key change at the same spot as the Whitney Houston version. Dolly has always spoken glowingly of Whitney’s version, telling Metro Newspapers, “for her to take my simple, sweet, heartfelt country song and be able to do it in such a big way was just spectacular.” While we’re on the subject of Whitney Houston and key changes, we encourage you to also give a listen to “I Have Nothing,” which is the track immediately after “I Will Always Love You” on the Bodyguard soundtrack, and serves as a companion piece of sorts to the first song, using the same keyboard sounds and Whitney’s stunning voice in top form as she takes the song to a higher plane (in a more subtle way than “I Will Always Love You”) in the final minute of the song.

“I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me)” by Whitney Houston

Songwriters: George Merrill and Shannon Rubicam

Whitney also experimented with key changes earlier in her career. “I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me)” from her 1987 Whitney album modulates a whole tone higher for the third chorus. “The song moves up a whole step from G♭ major to A♭ major,” observes Bora Uslusoy, who teaches several courses, including Writer, Engineer, Producer in the Home Studio. “This allows her voice range to shine even better in this higher register. And it does not sound cliché at all to my ears.”

“Overjoyed” by Stevie Wonder

Songwriter: Stevie Wonder

Sarah Brindell, who co-wrote Berklee Online’s Arranging for Songwriters: Instrumentation and Production in Songwriting course, provided commentary for this selection. She says: My favorite example is “Overjoyed” by Stevie Wonder, the master of key change. “Overjoyed” sets our ears up for chromaticism in the intro chord progression and then beautifully balances that with a diatonic progression in the verse. Stevie uses his voice as a “pickup” to modulate to higher keys, with an ascending melodic sequence that helps our ears move to new sonic palettes. Then eventually, the chords step back down chromatically to the original key, with his voice in parallel motion at the end. He takes us back home. It’s brilliant because that is so uncommon. Most of the time, songs either modulate and then stay in a new key or they just keep moving higher and higher, like in the case of “Love on Top” (by Beyoncé) or “Summer Soft” (also by Stevie Wonder). Everything is seamless movement in this song.

“Still Crazy After All These Years” by Paul Simon

Songwriter: Paul Simon

Cassandra Long, who teaches Berklee Online’s Lyric Writing course, weighed in on this one. She says: I absolutely adore the key changes in “Still Crazy After All These Years” by Paul Simon. In particular, my favorite is the whole step up, mid-way through the final verse/refrain. It’s imperceptible to the average listener, but gives the final refrain such a powerful lift! Of course, the same modulation occurs earlier in the song as well, and that provides some beautiful contrast in the bridge.

“Something” by The Beatles

Songwriter: George Harrison

George Harrison reportedly wrote this classic on his 26th birthday. The first verse and refrain ends with a guitar riff that leads back to C major for the second verse, and the second verse and refrain ends with the same riff, but it’s altered to lead to A major for the bridge. The bridge is in A major and it uses a bVII (a G major chord) and at the end, uses the same G major chord to modulate back to C major, for the third verse and refrain. “I think it’s the only example where a riff is altered to make the modulation into two different keys,” says Jimmy Kachulis, who has written many Berklee Online courses, including Songwriting: Writing Hit Songs. “It’s the Beatles! What do you expect?”

“Penny Lane” by the Beatles

Songwriters: John Lennon and Paul McCartney

Mike Sempert, who has taught several Berklee Online courses, including Culminating Experience in Songwriting, says his favorite Beatles key change is a Lennon and McCartney song: “Penny Lane” has these beautiful key changes with the verses starting in B major, ending in B minor and the chorus sections in A, which has a big emotional lift even as the tonal center moves down. Then at the end they give us the final victorious chorus in the home key of B and the song really soars.

“Hey Jude” by the Beatles

Songwriters: John Lennon and Paul McCartney

While we’re on the topic of Lennon and McCartney key change, we should probably discuss “Hey Jude,” which some may argue isn’t a key change at all, but a modal shift. But if it isn’t a key change, then why do the chords used during the first three minutes of the song—F, C, C6, C7, B♭, F/A, Gm, C/E—indicate that the song is in the key of F major, only for us to get a progression of F E♭ B♭ F, at approximately 3:11, which repeats throughout the last four minutes of the song? An E♭major is not a chord that fits in the key of F major. BTW, the timecode supplied earlier will be different on the video link, due to the “greatest tea room orchestra in the world” jam at the beginning of the performance. You could also make a case for the prosody involved here (whether you want to call it a key change or a borrowed secondary subdominant chord), as it literally takes a sad song and makes it better.

Let’s hear from Bonnie Hayes, Grammy-winning songwriter and Program Director of Berklee Online’s Songwriting graduate program: “Hey Jude” is interesting because it’s a shift of mode while the tonal center remains the same. For the most part, the song is in the key of F and uses—other than the couple of I7 chords—entirely the I-IV-V. It is true that earlier in the song, in the bridge, it slips into the key of the IV. In fact, several times in this song, the I chord becomes dominant, which leads us to the IV as a temporary home tonality. But this is a common secondary dominant progression and not really a modulation. But in the end, when the chords change to F-E♭-B♭, if we just read the chords, it looks like we modulated into the key of B♭ and are playing V-IV-I. But tonally, we’re still in F; the melodic phrases end on F and C, stable tones in the key of F, and the musical phrases begin and end on the F. F still feels like home. In fact, we’re in F mixolydian, the B♭ major scale reoriented as an F scale with a ♭VII. The mixolydian is a mode that has a sense of danger, of darkness to it, because of the presence of that ♭7 on the tonic chord of the key. It signals a kind of revolution, a throwing off of safety to take a walk on the wild side. It feels like the singer is telling Jude, “relax and take some chances, everything is gonna be okay.” Words to live by.

“betty” by Taylor Swift

Songwriters: Taylor Swift and Joe Alwyn (a.k.a. William Bowery)

For songwriters, knowing where to place a key change is the, er um, key. In this song from Taylor Swift’s 2020 Folklore album, she writes from the narrative perspective of a teenager named James, who’d previously been in a relationship with the title character before having “just a summer thing” with somebody who was decidedly not Betty. Throughout the first-person account we learn of James’ regrets and the songwriters constantly pepper the lyrics with hypotheticals about what will happen when James sees Betty again. What if James shows up at Betty’s party? That’s the question we keep coming back to in the chorus. Then when we get to the last chorus, Taylor’s narrator says, “I showed up at your party” twice before taking the song from the key of C major to D major on the third instance of the “showed up at your party” phrase (at approximately 4:07), heightening the narrator’s realization of everything that’s at stake with the title character, and perfectly portraying all of the drama and vulnerability of being a teenager: “Will you kiss me on the porch / in front of all your stupid friends? / If you kiss me, will it be just like I dreamed it? / Will it patch your broken wings? / I’m only 17, I don’t know anything / but I know I miss you.”

“Getaway Car” by Taylor Swift

Songwriters: Taylor Swift and Jack Antonoff

“Betty” isn’t Taylor Swift’s first foray into big key changes. “Getaway Car,” from her 2017 album, Reputation uses the same modulation from C major to D major, and is also about a love triangle that reaches its peak at a party. The difference, however, is where she chooses to change keys. “She modulates up a whole step in that bridge,” says Scarlet Keys, author of The Craft of Songwriting: Music, Meaning, and Emotion. “The result is the feeling of escaping the key (and the relationship at the party), which is pretty great storytelling. … When you decide to modulate, often songwriters will introduce the idea with some kind of musical foreshadowing melodic hint, but because she’s writing about two rebels, the new key comes out of nowhere, totally unannounced, like two bank robbers.”

“Love Story” by Taylor Swift

Songwriter: Taylor Swift

Prior to “Getaway Car,” Taylor Swift successfully employed modulation on her 2008 album, Fearless, with the song “Love Story”—which she wrote when she actually was a teenager!

“There are so many tools and techniques you can learn from her and incorporate into your own songwriting,” says Keys, “no matter what genre you write in.”

“Bohemian Rhapsody” by Queen

Songwriter: Freddie Mercury

This epic song, from Queen’s 1975 album, A Night at the Opera, is different from the other songs on this list in that when many of the key changes occur, they let the listener know, in no uncertain terms, that we’re in a brand new section of the song and a brand new section of the story, much like an opera. The fact that “Bohemian Rhapsody” has no repeated sections is something that Queen tell listeners right away in the title: one of the definitions of “rhapsody” is a song that is through-composed and has no repeated sections! The song also includes changes in time signature, but that would take an entirely different article to get into that, as well as changes in genre.

The first two sections include several subtle modulations between B♭ and E♭, two keys which share many of the same notes. The song begins with an a capella section in the key of B♭. A piano enters and we go up to the key of E♭ at approximately 0:22. Then we’re back to B♭ at approximately 0:49 as the section commonly referred to as the “ballad section” begins. At approximately 1:22 we’re back in the key of E♭. At approximately 1:48 we’re back to B♭ again. When we get to the brief guitar solo that bridges together the ballad section and the opera section, guitarist Brian May brings us into what we think is going to be the key of A♭ at approximately 3:01, but ends up being a semitone higher at A. This is one of the aforementioned changes that alert us we’re in a different portion of the story, as the opera section formally begins. There are arguably two additional key changes in the opera section before we definitively modulate back to E♭ at approximately 3:23. Surprisingly, there is no key change when we get to the rock section of the song, at approximately 4:07. The change in genre here is enough to signal that the story is moving to a different place.

When we get to the final section of the song, the instruments take us through a couple of subtle modulations, including a key change to B♭ at approximately 5:34, which then takes us to F at approximately 5:42, which is the key we end the song in. For a much more in-depth analysis of “Bohemian Rhapsody” than we have room for here, we highly recommend you check out David Bennett’s amazing video on the subject.

Valerie Orth, who teaches several songwriting courses, including Culminating Experience in Songwriting, says “it only makes sense that one of the most epic rock songs of all time would have key changes to intensify the theatricality and drama of the song. Much of the song’s lyrics contemplate big concepts, i.e. real life vs. fantasy, murder vs. a new life. Freddie Mercury even includes Bismillah, an expression in Arabic, meaning ‘in the name of Allah.’”

Though this is probably Queen’s best known example of key changes—and the one in which they employ the most key changes—the band continued asserting that they were the champions of key changes, employing them successfully in several songs, including 1977’s “We Are the Champions” and on the final single they released during singer Freddie Mercury’s lifetime, 1991’s “The Show Must Go On.”

Sean Slade (Producer and Author of the Culminating Experience in Music Production Courses) on His Favorite Key Changes:

Back in the early ’80s, when I was in a new wave band, the joke adage was: “If you want a hit, you’ve got to have a key change!”

“Dizzy” by Tommy Roe takes this principle to a comic extreme.

So in that spirit, my choices are:

The key change here is on the drastic side, moving from E to G for an outro chorus. But what makes it unusual is Mr. Big has the temerity to switch back to the original key for the final chorus (a stunt which almost never happens in the pop key-change world.)

Hudson Mohawke & Nikki Nair “Set The Roof” (ft. Tayla Parx)

More recently, this dance floor hyperpop from 2023 gets in on the key change game, but in a random, seemingly arbitrary way, which fits the genre perfectly.

“Dynamite” by BTS

Songwriters: David Stewart and Jessica Agombar

“Key changes in popular music are a death knell in the current era,” says Prince Charles Alexander, who wrote Berklee Online’s Genre Survey for Songwriters: Analysis and Application course, “but since K-Pop artists are just learning the rules, let’s check out ‘Dynamite’ by BTS. It modulates up a full step, moving from E major to F♯ major. The modulation hits at 2:40 in the song if you’re listening on Spotify; there is extra material at the beginning of the official music video.”

“Livin’ on a Prayer” by Bon Jovi

Songwriters: Jon Bon Jovi, Richie Sambora, Desmond Child

The mid 1980s were a big time for big things: big hair, big spending, big productions. All of these things often coalesce in the genre that some people refer to as hair metal, but it could really just be called hard rock with big pop hooks. No matter what you call this genre, big key changes are part of the formula, such as with this 1986 smash from Bon Jovi.

We asked Berklee Online course author Enrique Gonzalez Müller to weigh in on this one. To do so, he dug into the perspective of the courses he has written—Creative Recording and Editing Techniques in Music Production and Music Production: Maximizing Emotion through Performance, Arrangement, and Sound—as well as his own nostalgic recollections of how challenging it can be to learn harmony when you’re first starting out with singing.

He says: For the most emotional key change and the toughest-ever-harmonies-to-sing, I have to go classic. “Livin’ on a Prayer” by Bon Jovi always gets me. As a kid, I loved singing the chorus harmonies but when the key changes at 3:23, those high harmonies are impossible to belt out with as much oomph as these guys delivered. I still love it … and it gets me every time!

“Armageddon It” by Def Leppard

Songwriters: Joe Elliott, Rick Savage, Phil Collen, Steve Clark, and Robert John “Mutt” Lange

Def Leppard also went big in the mid 1980s. Their 1987 album, Hysteria caused enough hysteria amongst fans to sell more than 20 million copies and spawn seven hit singles, including “Armageddon It.” And though Def Leppard did go big in many ways, the way they change keys in this song is subtle enough that the untrained ear might not even catch it. After a T. Rex-style verse in the key of E major and a prechorus in the same key, they modulate a minor 3rd in the chorus. While this key change doesn’t follow the classic hair metal formula of making a leap up in the final chorus, to make such a big change from the verse to the chorus (and to make that chorus catchy enough to sing along to!) is no easy feat. “I love the minor 3rd modulation in this song,” says Songwriting Tools and Techniques co-author Pat Pattison. “If you’re going to modulate, really commit to it!”

“God Only Knows” by the Beach Boys

Songwriters: Brian Wilson and Tony Asher

Ben Camp, who wrote Berklee Online’s Songs Unmasked: Techniques and Tips for Songwriting Success course, weighed in on this one. Camp says: I love the harmonic dizziness this song brings. The verse starts in the most unstable form of a major triad: “I may not always love you” starts on the second inversion (D/A), then modulates up a whole step to the same structure (E/B) for “but long as there are stars above you,” and starts breezily walking down the scale (“God only knows what I’d be without you”), aiming at a satisfying E Major, but brazenly lands on E minor instead.

“Stand” by R.E.M.

Songwriters: Bill Berry, Peter Buck, Mike Mills, and Michael Stipe

There’s possibly some prosody at play here in this 1988 song by R.E.M., from their Green album. The lyrics are all about how we need to find direction and proper orientation in our lives—a place for us to stand where our “feet are going to be on the ground”—but by employing phase modulation during the song’s two final choruses (first at approximately 2:29, and then at 2:46) we’re made to feel disoriented. Basically, despite best laid plans, the Earth (and life) always has other plans.

“Somehow, Someway” by Chad Price

Songwriters: Chad Price and Matthew Johnston

Isabeau Miller, who teaches Topline and Vocal Production, says: My favorite key change right now is in a maybe not-widely-known song, “Somehow, Someway” by Chad Price. This song is such an inspiring, driving song that I often run or work out to, and when that key change hits it gives me that extra “oomph” and just feels so good and motivating.

“Thong Song” by SisQó

Songwriters: Mark Andrews, Tim Kelley, Bob Robinson, Desmond Child, Draco Rosa

Everything about this SisQó single pushes the limits of its format. In 2000, many hip-hop artists were releasing what could only be referred to as “booty videos,” showing scantily-clad models dancing along to their music. Since “Thong Song” is an ode to the article of clothing in the title, the music video focuses on women wearing it, which is to say they aren’t wearing much. (We’re choosing to link to the lyric video instead, BTW, but be warned that “Thong Song” features lyrics that some viewers will find offensive!) So at approximately 2:46 when the song dramatically changes keys (something we don’t frequently hear in hip-hop) it’s really the only logical choice to make an already grand song grander.

“The dramatic orchestral break followed by the over-the-top modulation from C# minor to D minor shows they knew not to take themselves too seriously,” says Camp.