The following information on music composition techniques is excerpted from the Berklee Online course Creative Strategies for Composition Beyond Style, written by Eric Gould, and currently enrolling.

As a composer, you will find that musical ideas come in various forms. You may be in the car and a rhythm might come to you. A snippet of a melody might occur to you while walking to the laundromat, or you may discover a chord or progression that you like and want to develop further. Any of these starting points can be the beginning of a highly evolved music composition.

Here we will discuss various music composition techniques and resources that will help you get started as you write your own piece of music.

How to Start a Music Composition

When you’re starting out with a blank piece of staff paper, there are infinite directions that you can go in. This is why you’ll want to begin with some parameters to narrow down those possibilities. Whatever your starting idea is, you’ll have several aspects to consider before embarking on your music composition. Some of the considerations are practical in nature and some are purely aesthetic, but having a grasp on the key issues from the beginning helps ensure the success of a project.

Let’s establish the things you should consider when kicking off a piece of music:

Why Are You Writing This Piece?

Having a purpose to do a project is one of the best ways to get you to sit in the chair and do the work. It also defines what you’re trying to accomplish musically. Think about how many great pieces of music are about some person, event, or story. When you have a motivating factor, it tends to lend musical clarity as well.

Ask yourself, what is the motivation for writing this piece of music? Is it…

- for your next recording?

- to commemorate something or an event?

- for a tribute?

- for a competition?

- as an exercise or etude?

Templates

Understanding how to use a template for the drafting phase can greatly enhance the compositional process. Templates allow you to get to the creative ideas faster by eliminating the steps involved in setting up a score just to record your ideas, and by helping to refine a method for getting to those creative ideas.

Here are three types of music composition templates:

Lead Sheets

- Two staves, with the melody on the top staff

- Harmony and rhythm on the bottom

Small Ensemble

- Three staves

- Horn voicings, or words and melodies on the top staff

- Rhythm section and bass lines on the bottom staves

- If voice and horns, you can use the bottom staves as a lead-sheet sketch

Large Ensemble

- Two grand staffs

- Allows for overlapping voicings or bass lines

Music Composition Software

Software templates are extremely helpful because, with a few clicks in a good software package, you can use the materials from your sketch directly in a score that you can build from the same file. Software templates also allow for easier editing, and allow you to take extensive notes on your piece or sketch as it evolves. Erasing the notes is as easy as selecting and deleting.

Sibelius and Finale

Sibelius and Finale are the two major music composition software programs, and Berklee Online offers courses that will give you thorough instruction on how to use them.

- Music Notation and Score Preparation using Sibelius Ultimate

- Music Notation and Score Preparation Using Finale

Berklee Online also has courses that will teach you how to use digital audio workstations (DAWs) such as Ableton Live, Pro Tools, Reason, Logic, and Cubase.

What is the Instrumentation?

Sometimes instrumentation is a practical consideration, and the piece of music is simply adapted to the resources and expertise available to the composer. Many times, however, the decision about instrumentation is part of the aesthetic of the piece. You may want to write a tune for your band to perform. Perhaps a string quartet has asked you to write a piece of music. Maybe a vocalist just wants a tune to add to their repertoire, and all you need to create is a lead sheet. Somewhere down the road, you may get an opportunity to write for a big band or full orchestra.

If you’re an inexperienced composer, you should start off writing for smaller ensembles, and then expand upon the arrangement. For example, you can go from a lead sheet to a quintet arrangement, to an octet, and then to a big band, building upon what you have at each step.

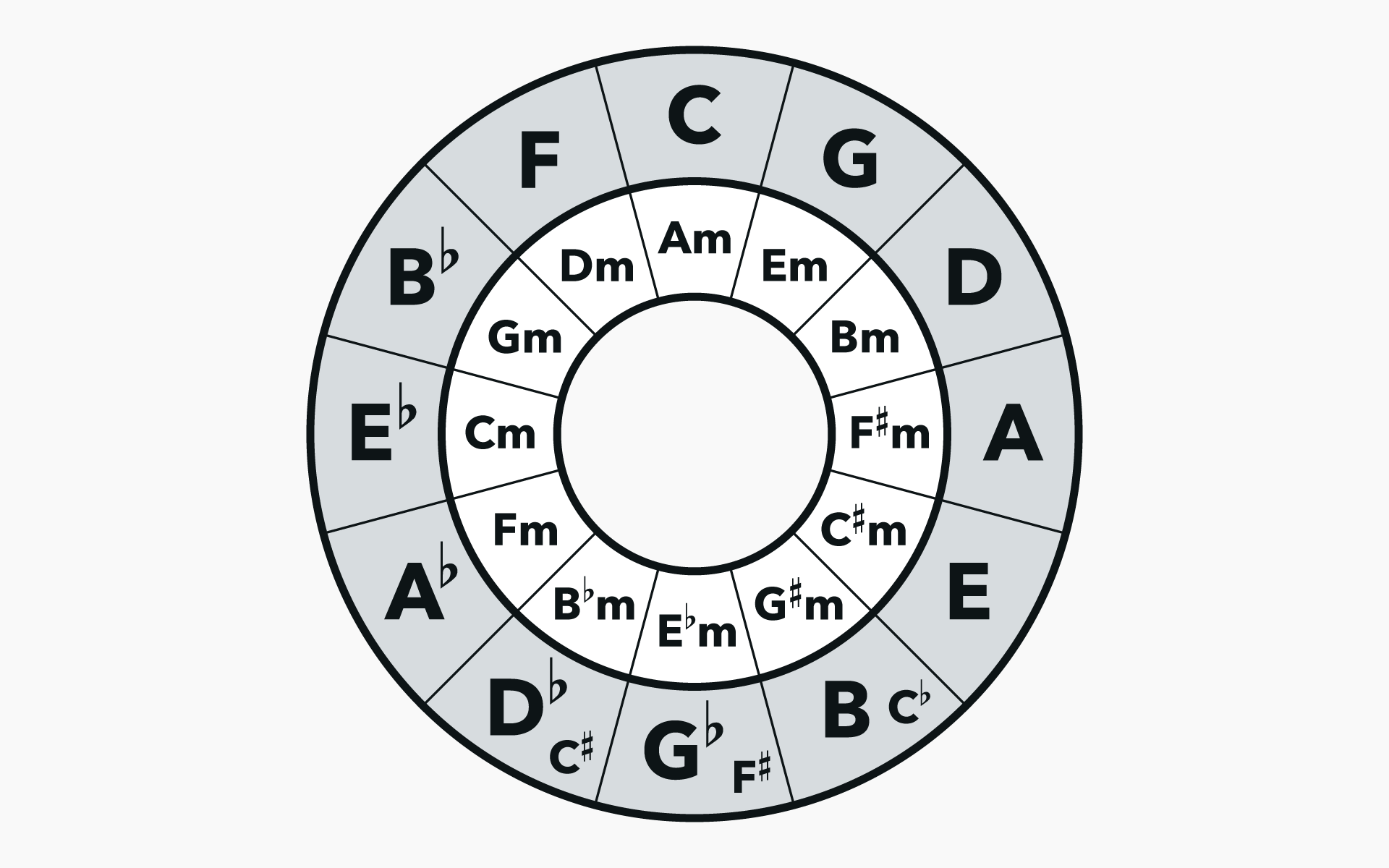

What Key or Tonal Center Will You Start in?

This decision can be influenced by many factors, including the instruments for which you’re writing.

How Long is the Piece?

Will your piece be a tune, a short arrangement, or an extended composition? You don’t want to start your composing career with a 30-minute-long masterwork. Build toward longer works by first coming up with a good melody, adding an intro and a coda, and then extending the piece. Many times, the length will be dictated by practical constraints like radio airplay, concert length, or budget.

What is the Form?

Defining the form of the music composition beforehand will help you to write the piece. If you know that you’re going to have an intro, bridge, and coda, you will approach the other sections in a way that will prepare for their incorporation into this larger framework. Planning the form in advance of the composition will also help you in deciding the character of the piece, as you will have to think about what will distinguish one section from another.

How will the Harmonic Rhythm Move? Statically or Modally? Are they:

- Long durations (more than one bar)?

- Short durations (one bar or less)?

- All of the above?

What do you want the character of the piece to be?

- Love song?

- Jagged and edgy?

- Traditional?

- Bluesy?

- Ethereal?

- Something else?

Do You Have a Time Signature in Mind?

If a song is a waltz, you would write it in 3/4. Funk and dance rhythms are most often in 4/4 time. Afro-Cuban rhythms are typically 6/8, 12/8, or 4/4. Any combination of beats per measure is possible. With compound meters (e.g., 7/8, 7/4, 9/8, etc.) the potential for complexity increases, and this can create a feeling of tension, but these time signatures can be very engaging. The bottom line is whether or not it sounds good!

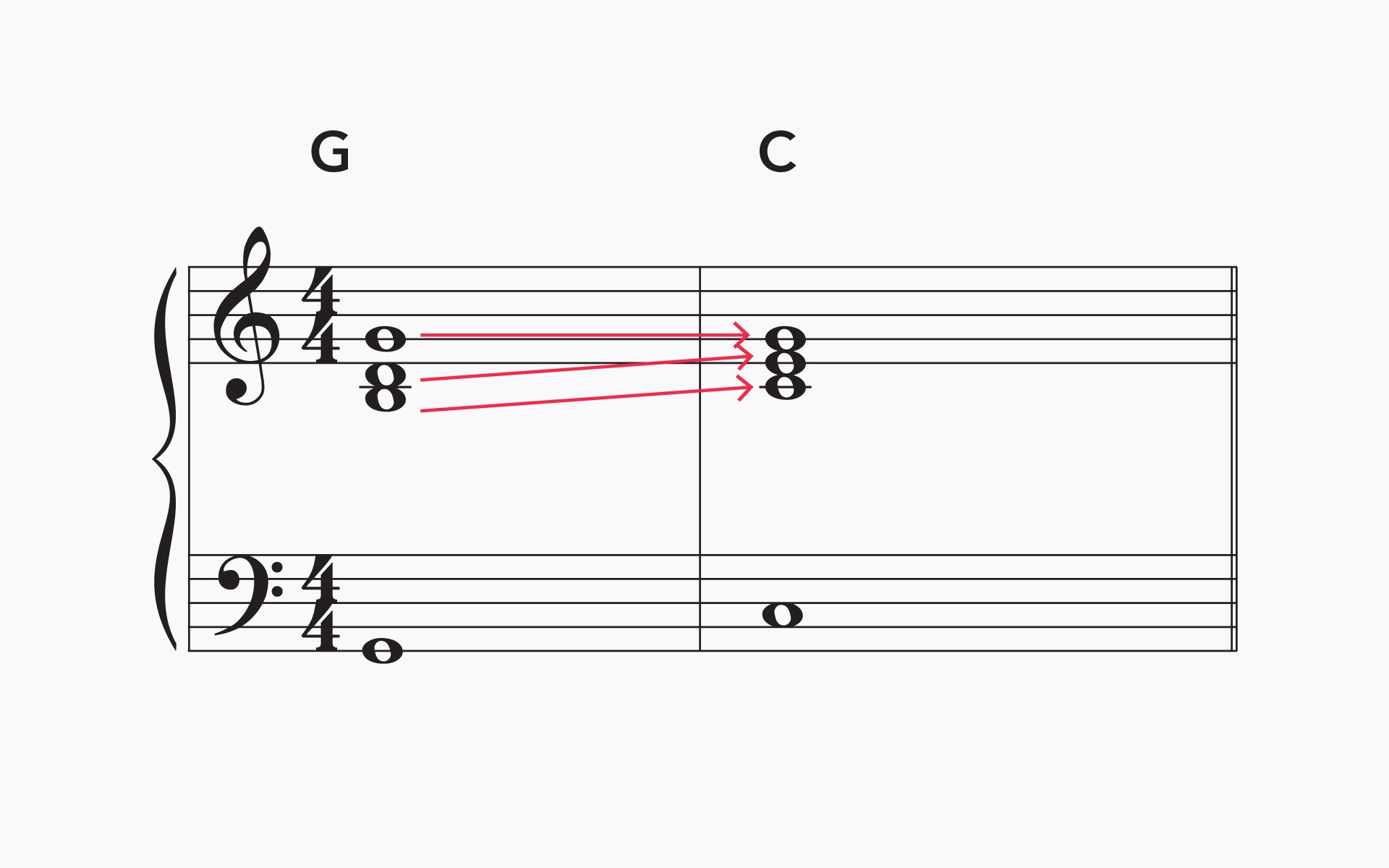

Harmonic Rhythm

If you’re employing static or modal harmony, choose a chord or two that captures the character of what you’re trying to convey. If it’s a chord progression, decide what the duration of the chords (harmonic rhythm) will be.

Melodic Character

Sing or imagine a few beats that capture the character of what you’re trying to convey. Don’t worry about coming up with the perfect notes, and don’t try to write a piece—just come up with a fragment that has character, understanding that you can adjust it later.

In building the skill required to start from various points, limiting your options allows you to focus more on the process itself. You can transfer what you learned to a larger set of options as you grow. Like any other skill, compositional skills are cumulative—each thing you learn will prepare you for another set of challenges. Also, like any other skill, solid fundamentals are essential to sustained growth.

Sequencing

While this doesn’t mean feeding your musical fragment into your favorite sequencing software, the concept is very much the same. Sequencing involves repeating an idea with some sort of variation, most commonly involving pitch. The most common type of sequence involves simple transposition of the fragment to various starting points either in the key or tonal center or outside of it. If the transpositions occur within the confines of a key, then you will most likely need to change the intervallic relationship of the notes while retaining the basic shape.

Augmentation and Diminution

The value of a rhythmic element or an interval can be either increased (augmented) or decreased (diminished) upon repetition to create a variation. This is another widely used compositional device.

Pitch Augmentation (widening) and Pitch Diminution (contracting)

Likewise, you can widen the intervals within a melodic fragment, creating a sense of drama in the music while varying only one element.

Varied Harmonic Rhythm

One of the most common places for the harmonic rhythm to increase is in cadential passages. Increasing the frequency of harmonic change creates a sense of excitement and anticipation. Likewise, slowing down the harmonic momentum creates a sense of reflection, allowing the composer and listener to dig more deeply into the harmony of the moment.

I hope you find these music composition techniques helpful as you begin your piece. Keep in mind that there is so much more to learn in my 12-week Berklee Online course, Creative Strategies for Composition Beyond Style. Below I’ve included some resources to help you continue to learn music composition, including music composition books and more music composition courses from Berklee Online.

Music Composition Books

If you want to know how to learn music composition on your own, music composition books are a great place to start. Berklee Press has published several music composition books that will help you learn the basics of music notation. Here are a few music composition books from Berklee Press to check out:

- Music Notation: Preparing Scores and Parts

- Finale: An Easy Guide to Music Notation

- Berklee Contemporary Music Notation

Discover more music composition books from Berklee Press

Music Composition Courses

Berklee Online has more than a dozen music composition courses that will help you take your skills to the next level, all while composing professional work. You can also earn a professional certificate in Music Theory and Composition. Check out the following music composition courses:

- Contemporary Techniques in Music Composition 1

- Jazz Composition

- Music Composition for Film and TV 1

- Music Theory and Composition 1

- World Music Composition Styles

EARN A PROFESSIONAL CERTIFICATE IN MUSIC THEORY AND COMPOSITION