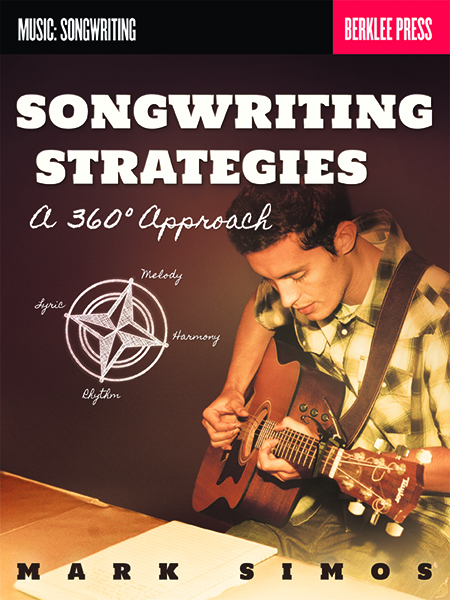

Mark Simos is a songwriter, educator, and author, who has written for Alison Krauss, Ricky Skaggs, Del McCoury, Laurie Lewis, Jimmy Barnes, and so many others. His book Songwriting Strategies (Berklee Press, 2014) provides an inspiring overall approach for songwriting, and countless tips to help you become more productive and to make your songs more captivating.

Before I present you with my interview with Mark, I want to wax personal, for a minute. You know, I have this gig, editing books for Berklee Press, in part because I want to read books like this so much. It’s actually a very indulgent perch, at times. I get to ask experts to clarify every last little stinking detail, because I’m their editor, and by some miracle, it’s my job to push them to reveal the “whole truth” about what they are doing in their art. And I just wallow in this kind of clear, practical talk about the processes of music making.

Anyhow, I am writing this blog post having just returned from Nashville, where I spent a day co-writing another Berklee songwriter (soon to be another published Berklee Press author), Shane Adams. Together, in just one day, we co-wrote twelve songs and recorded demos of four of them. It was honestly one of the most productive days either of us has ever had, and we got some really nice songs out of it.

Throughout this freakishly intense charrette, I had much of Mark’s Songwriting Strategies wisdom guiding my process. His book gives you a flexible framework for developing song ideas, as well as solid practical advice about finding and honing concepts. So, as always, I am very pleased to present Marks’ songwriting advice. And I’m not just a spokesman; I’m a customer!

Also, I want to tell you that Mark has been developing some audio files that illustrate some the ideas in his book. He’s hosting them on his own website, so if/when you work through his book, check them out.

Here’s my interview with Mark.

Jonathan: What’s the difference/relationship between a good song and a hit song?

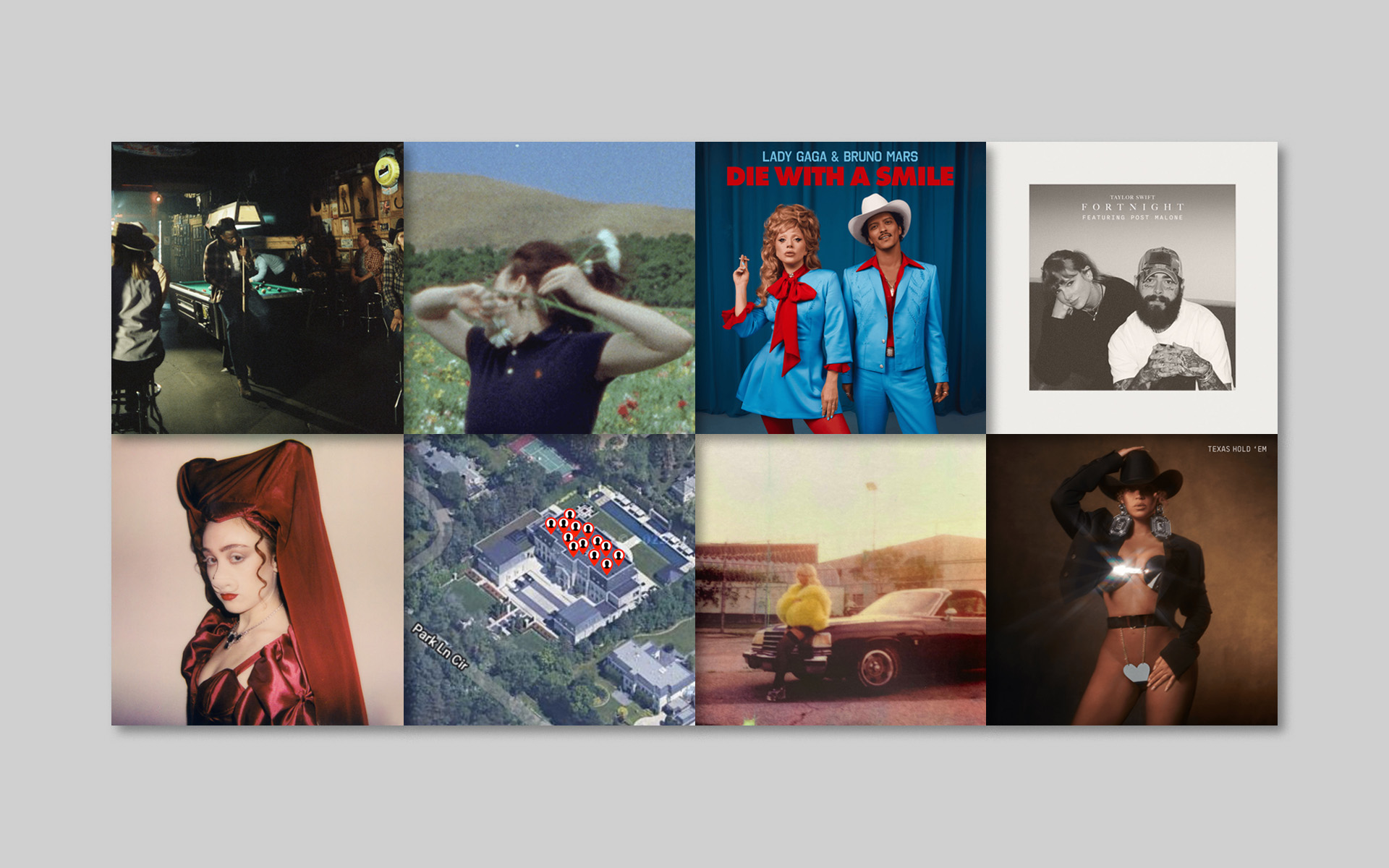

Mark: A good question—perhaps a hit question! And a question the young student writers I work with at Berklee constantly wrestle with. They are trying to develop their craft and technique, and to find a unique voice and sound. At the same time, most are surveying with some trepidation the competitive and churning music industry they’re about to dive into. Should they change their aesthetic to suit what the “market” seems to be asking for? Or should they bravely pursue a more independent artistic path, ignoring fashion and fad? When does a savvy study of current hit songs devolve into formulaic and soulless writing? And when does pursuing a more idiosyncratic musical vision become simply an excuse for indulgent songwriting, a lack of attention to craft—which in the end comes down to not caring whether you engage and move the listener?

I know what I believe. The first question to attend to is: what’s the difference between a good song and a great song? That difference is the same dedication and hard work required to make a sort of okay jazz soloist into a monster. But where great performers and improvisers must practice their scales and chops, to be a great songwriter, you have to put your 10,000 hours in writing songs.

In my book I encourage writers to practice the art of catching song seeds: you must catch hundreds of seeds even to learn to recognize a seed for a song that is a great, deep idea. Then you must not settle. In my teaching, it’s when a student has worked on perhaps a dozen revision passes on a song that we get to that state where every word, every syllable, every note, every chord, is steeped in intent and certainty. That quality of greatness has to do with love and attention to the essence of the song. Sure, you must have something deeply human to communicate with that song. But both as a songwriter myself and as a teacher, I have found it not too helpful to beat myself up about that. Life gives you what you need to say. The question is, have you done the work to say it—sing it, play it—in a songwriterly way?

Once you can write a great song, the question of which great songs become hits and which don’t is a different question; and this is not a question that need stop you in your tracks. And the hit songs that are not great songs—to your ear, anyway—need not concern you.

How does the songwriting process change across different genres? Say, rock vs. hip-hop vs. country?

Another fascinating question! One purpose of my book was to create a more precise vocabulary for talking about the many kinds of creative processes by which songs can be developed. That vocabulary can usefully illuminate distinctions across genres. And a 360º songwriting practice can prepare you to work in multiple genres with more versatility and process flexibility.

A few broad trends can be seen. In the American Songbook era, in musical theater writing, and in much early pop music writing, there was a clear distinction between lyricist and composer roles: words vs. music, where music meant both melody and harmony. It was quite a shift, actually, when solo singer-songwriters began to write whole songs. That led, I think, to some romanticized myths about songwriting as only being authentic when it’s a completely intuitive, organic, creative outpouring: break up with your boyfriend/girlfriend, stare mournfully out the window, and the God(dess) of songwriting drops the inspiration on you—boom! This devalues the role of craft, of revision, in process. It also, in a subtle way, also devalues the 360º principle that the musical idea can come first, theme and even emotion following.

Now we see other shifts, with new collaborative roles and with technology playing a role far earlier in the writing process. Beat makers and producers build tracks, often around simple, cyclic chord sequences rather than the more narrative progressions of older genres. Topline writers create melody and lyric over those tracks, typically in a very interwoven way. We’ve moved from lyrics vs. music to track (chords plus production, song form, orchestration) vs. topline (melody and lyrics). Hip-hop has changed process in other ways: blurring composition and improvisation (composed vs. free-style rapping), and radically changing the rhythmic structure of lyrics—in hip-hop as a genre, in hip-hop sections integrated into straight-up pop songs, and also in hip-hop influences finding their way into mainstream country and other genres.

As songwriters become more experienced, how do their processes and relationships with their songs tend to change?

I think there are rhythms in one’s creative life, just as in personal life. Many of us start writing songs in our teens, when our emotional lives loom large in our awareness. Songwriting thus begins very personally, with songs as intensified expressions to ourselves and those around us: gifts, supplications, declarations. Such raw passion and intensity is easy for cooler heads (and songwriting profs) to disdain, but it’s the necessary fuel to drive us through the hard work of gradually transmuting those outpourings into something more focused and communicative.

So what I hear and encourage, in student writers developing their art before my ears, is first a spiraling outward: a necessary detachment, to some degree, from such personal connection to one’s songs, an ability to step outside the song and hear it as a listener will hear it. If you want songwriting to be part of your profession, you will need this widened scope and range, or else you will pay a huge personal and psychic cost for every new artistic foray. But you will also reach points, throughout your professional life, where it is necessary to spiral in again: to rediscover and reconnect with your personal voice and artistic mission, to “strike your own note,” as the poet Seamus Heaney wrote.

I’ve just gone through a period of that sort myself, on my sabbatical this past spring and summer. After working for years on Songwriting Strategies, which aspires to be a book you can apply to writing in any style or genre, I decided to give myself the chance to re-connect again with traditional music, the source material I love and know the best. It has been a period of renewal that let me revisit old favorites and even my own earlier work with fresh ears, to consolidate a lot of the technical knowledge I’ve acquired and make it my own in a new way.

What are some typical struggles that songwriters have, or traps that they fall into that compromise the quality of their songs?

Besides the shift from personal to more crafted songwriting I described above, I see songwriters wrestle with a few big issues. As teachers, of course, we’d like to believe the big problem is lack of knowledge, since that is the easiest problem (we think) to remedy by lecturing to people. In reality, I think two bigger problems get in the way; if you address those problems, writers will seek out the knowledge they need of their own will.

The first problem is simply hearing your song as others will hear it. I suppose you could call this the songwriter’s version of the “Golden Rule.” It doesn’t mean writing in a calculated way for what you imagine an abstract “market” or “audience” wants to hear. It means stepping outside the cloud of personal context that colors how your song resonates for you, and trying to hear it as a listener, as if for the first time. As you learn to do this, you catch an amazing number of problem spots for yourself. Friends and fellow songwriters can help by sharing their own listener impressions with you, as “wise listeners”—a phrase I borrowed from science fiction writer Orson Scott Card, who writes of “wise readers” in the same way.

The other big problem I see is the temptation to use your other strengths in ways that hold back your songwriting. If you’re a strong vocalist, for example, your instinct will be to throw all that vocal firepower at your song, even when it’s only half-written. You’re “selling it” too early. Similar problems can crop up with instrumentalists, who might lean on impressive licks covering up an essentially banal and derivative chord progression that doesn’t have a real idea or a story to it. It takes courage to identify your strengths, then challenge yourself to hold those elements back to test whether the song itself is doing the work you want it to do. But that’s how you get to truly great songs—songs with their own legs and life, songs other artists will want to record, songs that will live longer than you.

Do you have any songwriting insights that you share with your students that commonly lead them to make significant breakthroughs?

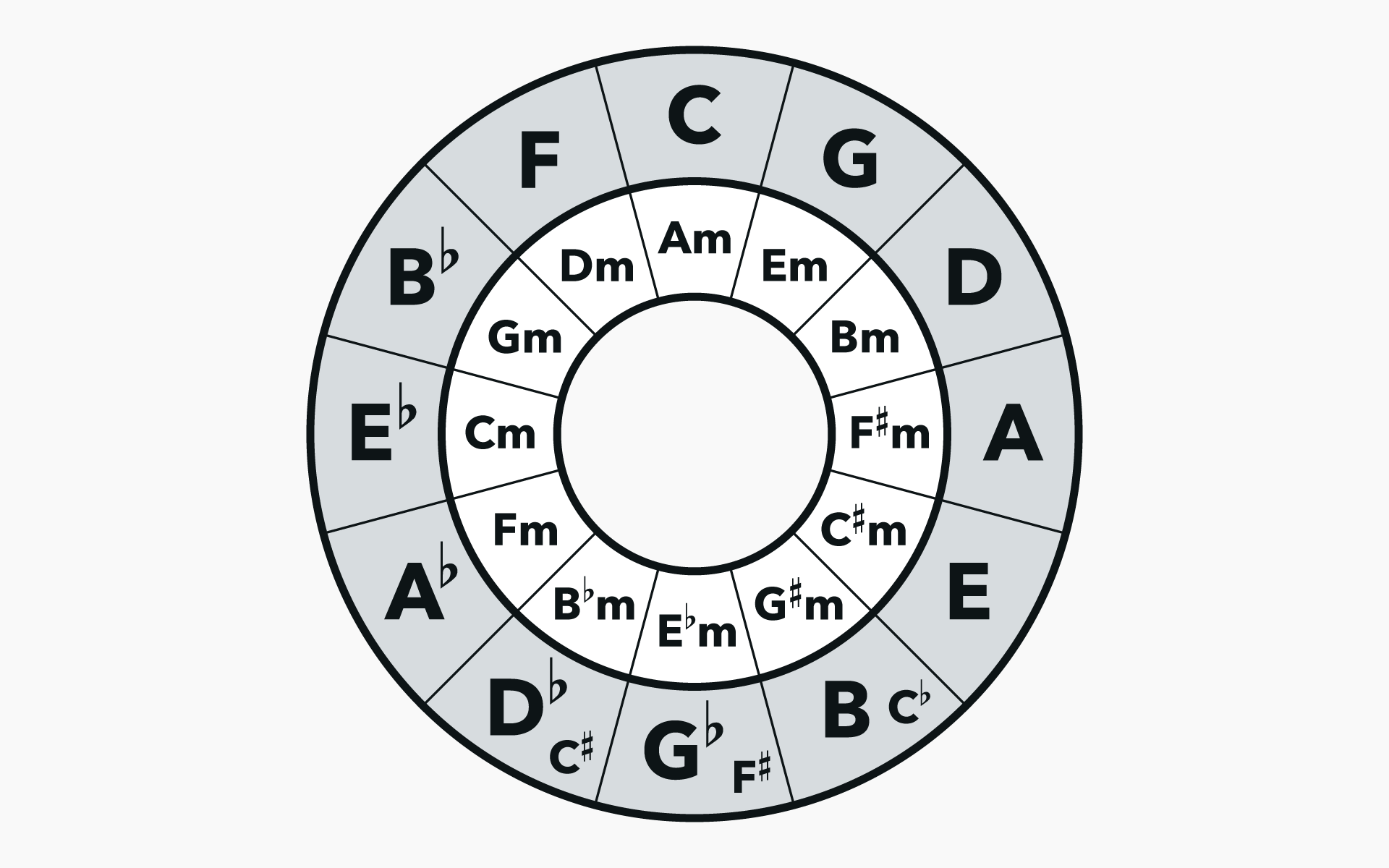

Well, the entire 360º songwriting approach I describe in my book is like a laboratory for creating those kinds of breakthrough experiences. Essentially, I’ve found that all writers fall into comfortable processes, ways of writing. They may get quite good at writing songs that way. But if they are willing to experiment with a different process, they will write new and different kinds of songs. Even if that new process seems initially uncomfortable, even a bit silly, it can often get you to true and deep material you could not reach any other way. These process challenges will be different for every writer and will change over time; but the Songwriter’s Compass provides a roadmap for continually identifying new process challenges to stretch yourself as a writer.

Beyond this exploratory approach to process, I have found particular moments in writing, and in mentoring writers, that have a quality of epiphany. Once you commit to the idea that you are creating a world in each song, and are inviting the listener into that world, you can take that creative work as deep as you want to go. In certain songs, you hit a point—often in trying to write the bridge, as it turns out—where you need to ask: “What does the singer (in the world of the song) discover or figure out through the very act of singing this song?” This is one of what I call the “Golden Questions” (maybe related to that Golden Rule!). In trying to answer this question, the songwriter often figures out something they themselves didn’t know when they started writing the song. Content and process mirror each other at these moments—like one of those cool M. C. Escher paintings that come flowing out of their frame. When you finish writing one of these songs, you are a different writer than when you started.

Your book discusses starting the songwriting process from any seminal idea: lyric, melody, harmony, etc. But what’s your favorite standard starting point, and why?

I pride myself on writing from all directions, and enjoying writing from all directions. But lately I have gotten excited again with the approach of starting, oddly enough, simply from a chord progression. I have an exercise I’ve now shared with countless students that I call “Hank Williams in Hell.” You write a verse and chorus starting with a chord progression, using only the plain chords I, IV, and V (1, 4, and 5 as they’d say in Nashville!). You have only straight four-bar phrases to use, and get just one chord per bar—no fancy stuff to make the progression more rhythmically exciting: just the chords tolling along like a beautiful mosaic.

The “In Hell” rule is simply this: once you’ve used a chord sequence for a line (say, 1 4 5 5 or 1 5 4 1 or 5 4 5 5) you can’t use that sequence again in the song! It seems like such a simple restriction. Yet the process of “thinking through” a progression this way is totally transformative for many new writers. You must write something of a narrative in the progression. If you hold off worrying about lyrics, or melody, or even what the song is going to be “about” or the emotion, until you have a progression you really like, the rest of the song will often come to you in an almost magical way. One student came back and said, “I just wrote the first happy song I ever wrote.” Here are two links to songs two students wrote using the Hank Williams in Hell technique.

This is from my former student Georgia English:

This is a cool example because it’s an AABA song.

Another to listen to is Jen Starsinic’s “Six Foot Three.” She uses wonderful extended phrasing at the ends of lines but it doesn’t change the overall shape of the chord move for that line in relation to the others.

You are a famous hoarder of potential song ideas. Do you have any tips for organizing them?

At one point, I wanted a whole chapter of the book to be about how to keep track of your song seeds! It’s a constantly evolving puzzle for me. I do know that you need to have really easy ways of catching them fast. For the past couple of years, I decided to move away from physical notepads and did everything on my smartphone Notes app. I wanted to experience life like many of my younger students who have all evolved to have what I call “text-hensile” thumbs. Now that I’m faster with it, I’m going back to little notebooks again. I guess I’m old school.

I do think it’s a powerful practice to create a single large file (realistically, on the computer) to be your “Song Seed Mother Ship” where you gradually siphon all your stray notes and seed lists into one big pool. Organizing that master list will become its own journey of discovery for you. It’s good to allow for seeds of different types (lyrics, ideas, melodies, chord progressions, weird found chords, photo or sound inspirations, etc.), but also to have your own quirky categories. I have “Cat fiddle tune names” for example, with titles like “There Will Be a Mouse” and “Meaty Fresh.”

That master list becomes something you can turn to when preparing for a co-writing session, or responding to a project opportunity, or just to energize yourself to write on days when the energy is there but not the starting idea.

What abstract values do you have regarding song construction? Like, are you generally looking for contrast, or unity, or continuity, or surprise, or expressive depth, or catchiness?

Just as I believe great songs can start from seeds in any direction (or facet), I believe there is a vast library of song forms and structures—a sort of pantheon of Platonic archetypal beings—the God of AABA, Wordsworth’s ghost holding up ABBA, and so on. Every genre has preferred forms, and it’s great to master these, to know how to inhabit them un-ironically, as well as when and how to stretch and blend them. An example would be the immense variety of variations on blues forms Dylan explored in his corpus, beyond standard forms.

It’s also good to know your habits and preferences, and thus some of your own weaknesses and blind spots as a writer. In my case, I love a certain narrative flow in my songs, and must really work at allowing unadorned repetition. I’d probably be a better pop writer if I could get over that, but it’s like an itch that I’ll always scratch, left to my own devices. I bring that self-knowledge into collaborations. It makes me at least more tractable, less likely to insist on my own aesthetic at every turn.

My sabbatical research gave me a new perspective on this. My study of traditional music—the deep phrase structure of fiddle tunes and old ballads for example—has revealed structural principles that I believe are very ancient and yet remain very potent, applicable to any style or genre. A characteristic of these types of structures is a kind of “sleight of ear.” They create apparent variety and surprise using the most parsimonious of materials. You can listen to them endlessly and keep hearing new mysteries reveal themselves. My current area of new delight is diving deeper into these forms—the poetics of simplicity.

To me, one of the big takeaways of your book (perhaps unstated) is that attention to all these different dimensions of craft leads generally to an overall comprehensibility in the songs that result. Could you point us towards a song or two that you feel exemplifies good multidimensional craft, and give us some guidance about what to listen for?

To be clear, one can use materials in my book to expand your range as a songwriter, and still not immediately achieve that balance of all the dimensions. For example, if you always write lyrics first, and therefore tend to throw chords together a little casually, you’ll learn a lot by writing chords first, really composing a progression. Do this enough, in enough different directions, and you gradually gain control over materials you previously were not attending to as well.

Still, a guiding aesthetic goal for me is certainly a kind of song where each aspect is contributing to the overall theme and emotion. That doesn’t mean all elements can stay in the foreground and compete for the listener’s attention. You might want lyrics center stage for verses that advance scene setting, and later the back story. Then melody might move into the spotlight in the chorus, to evoke the emotional anchor of the song. But applying craft to each element, even if the materials are very simple, is a level of songwriting art that we sadly are hearing less of these days.

Who were the masters of this kind of writing? I think the great American Songbook lyricists and composers achieved it in one respect—in part through collaboration in many cases. Johnny Mercer spent a year finding lyrics worthy of Hoagy Carmichael’s music for “Skylark.” That’s a lot of patience! In our generation, the Beatles, and some of the early masters whose work still provides a benchmark for us all—James Taylor, Paul Simon, Joni Mitchell, Stevie Wonder, for example—achieved this kind of prismatic perfection of multiple aspects of the song in unity.

A song I’ve returned to over and over again in classroom teaching is James Taylor’s “Sweet Baby James.” You can look into every aspect of that deceptively simple masterpiece—lyric, melody, chords, metaphor and storytelling—and continue to find little chiming correspondences, mirrors, and echoes.

Perhaps it’s not “comprehensibility” that lies at the summit of this mountaintop, so much as a kind of richness and resonance. These are the songs that are timeless because they hold inexhaustible mysteries and delights, that bear up to repeated listenings, new interpretations. This is certainly what I aspire to in my own writing. And it would be nice if a teaching book wound up being worth a second read as well!

James Taylor: Sweet Baby James

STUDY SONGWRITING WITH BERKLEE ONLINE