Learn what the circle of fifths is, how to read it, and how it helps you understand keys, sharps, flats, and harmony

The following information on the circle of fifths is excerpted from the Berklee Online courses Music Application and Theory, written by Eunmi Shim; and Music for Beginners, written by Joe Mulholland, Yumiko Matsuoka, and Gaye Tolan Hatfield. Both courses are currently enrolling.

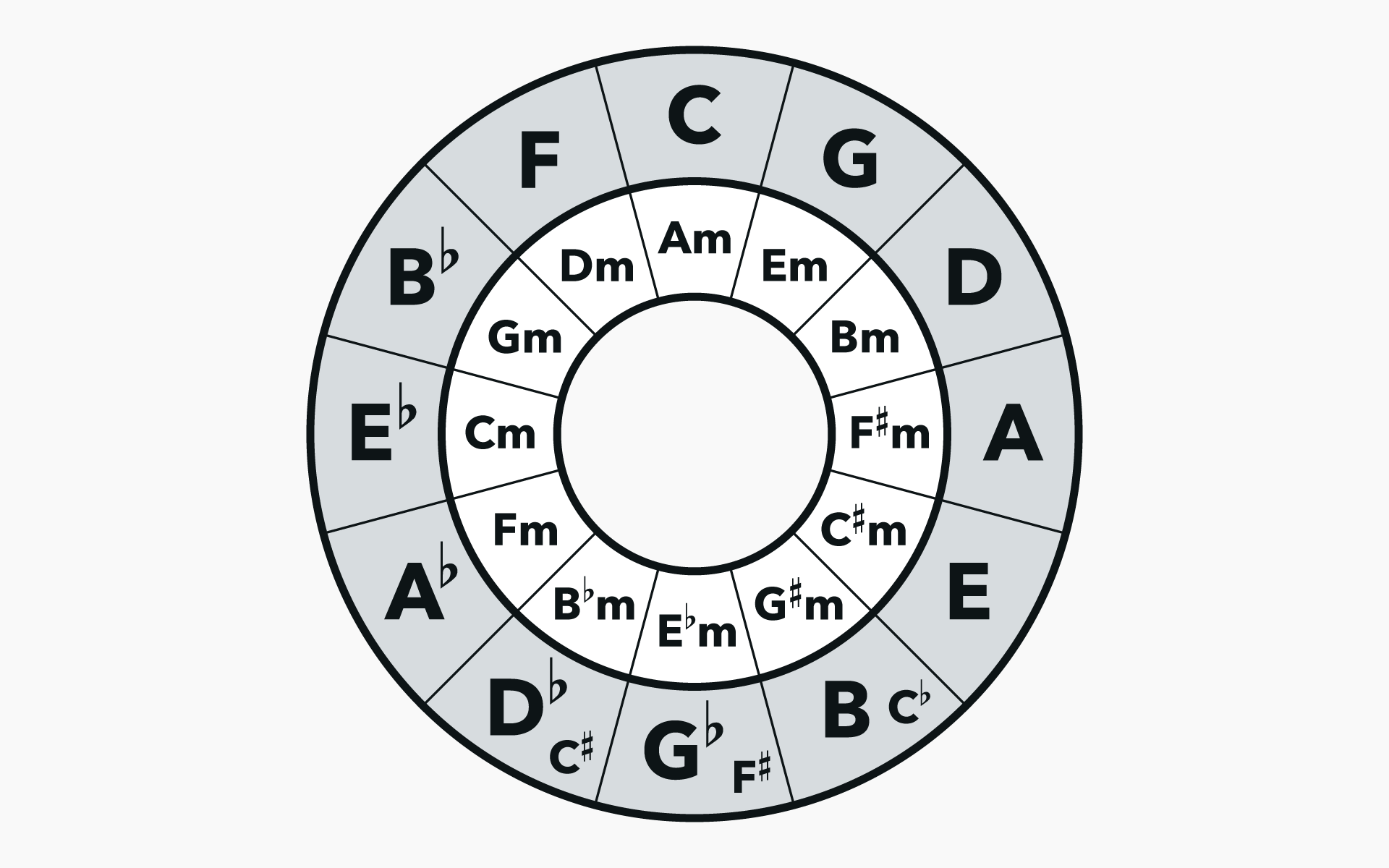

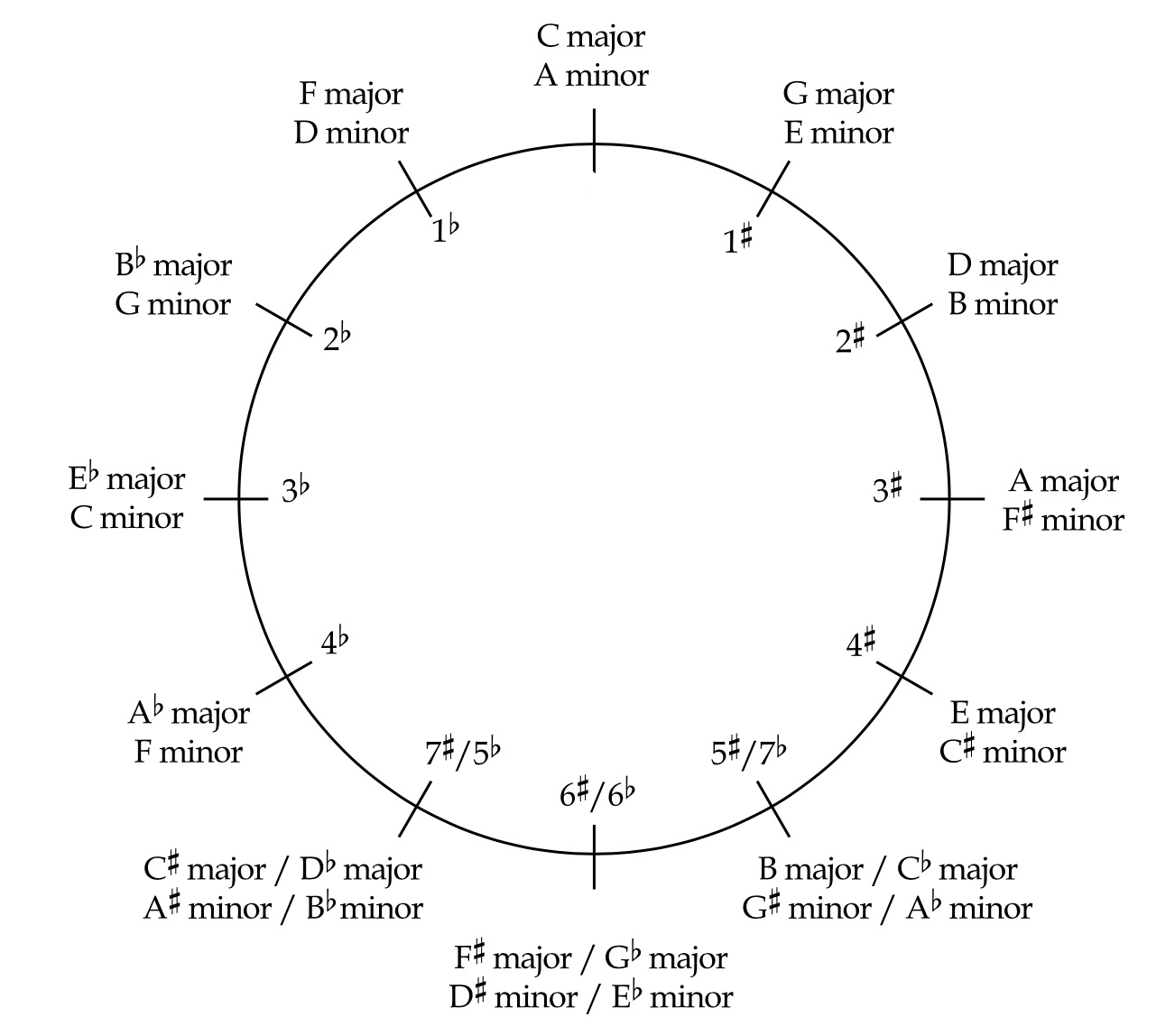

The circle of fifths is arguably the most helpful way of visually organizing Western music theory’s 12 chromatic pitches for learning. Seeing the notes laid out in a circle will help you unlock an understanding of how major and natural minor scales are organized, and also how they are related to each other.

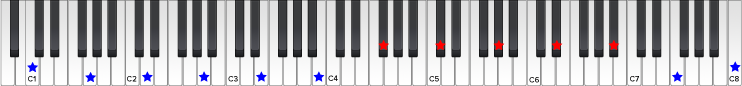

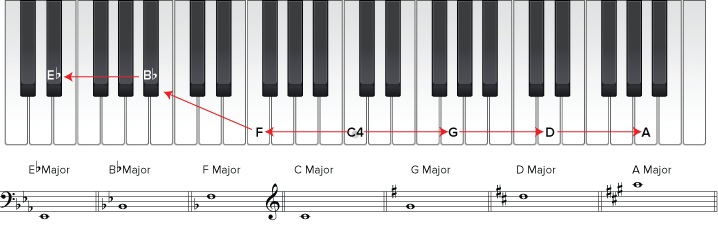

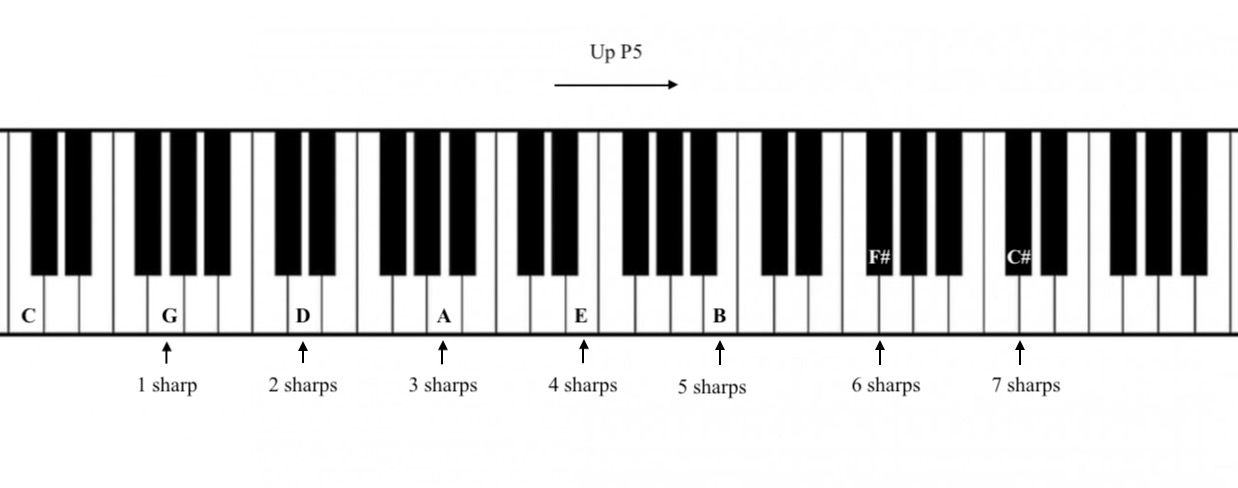

So how do we first acquaint ourselves with the circle of fifths? Before we even look at that circle, take a look at your keyboard. Start at the lowest C (the farthest on to the left) and go up in fifths. Play the starred notes:

Note what happens: we end up back on C. In the process, we have touched all 12 possible notes: C, C♯, D, D♯, E, F, F♯, G, G♯, A, A♯, and B. Let’s see if we can express this in a simple way. First, a quick review and an exercise to point us in the right direction.

You may already know that notes can have more than one name. For example, C♯ is the same as D♭, and A♯ is the same is B♭. Two notes spelled differently are called enharmonics. It is a term you will hear often at Berklee and in the professional music world.

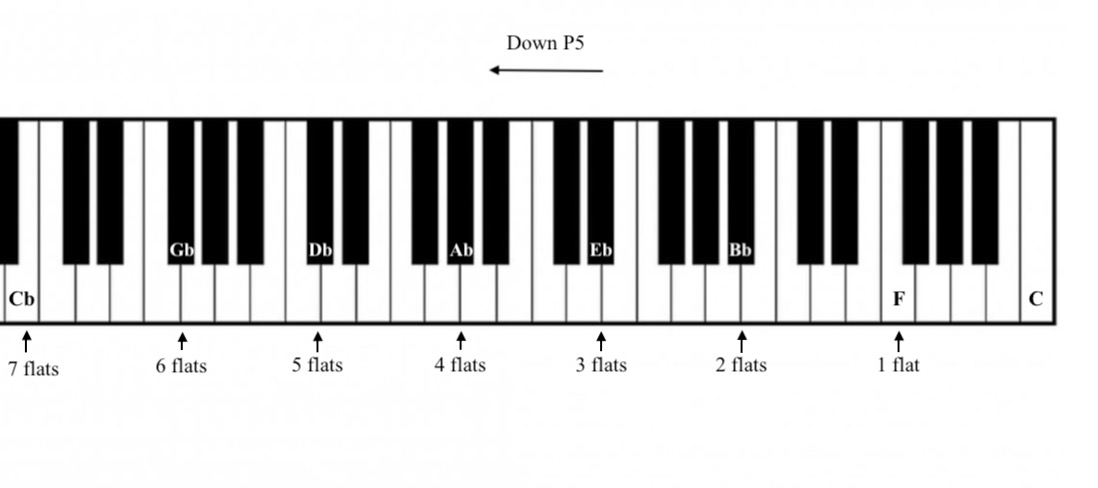

Take a look at the full keyboard of 5ths. Then, write down the descending notes from the highest C. Name the black keys using only flat names this time.

STUDY MUSIC THEORY ONLINE WITH BERKLEE

When we do this, we discover that, as we go up in 5ths from C, we get scales with more and more sharps. The reverse is true as we go down from C: we get scales—and key signatures—with more and more flats.

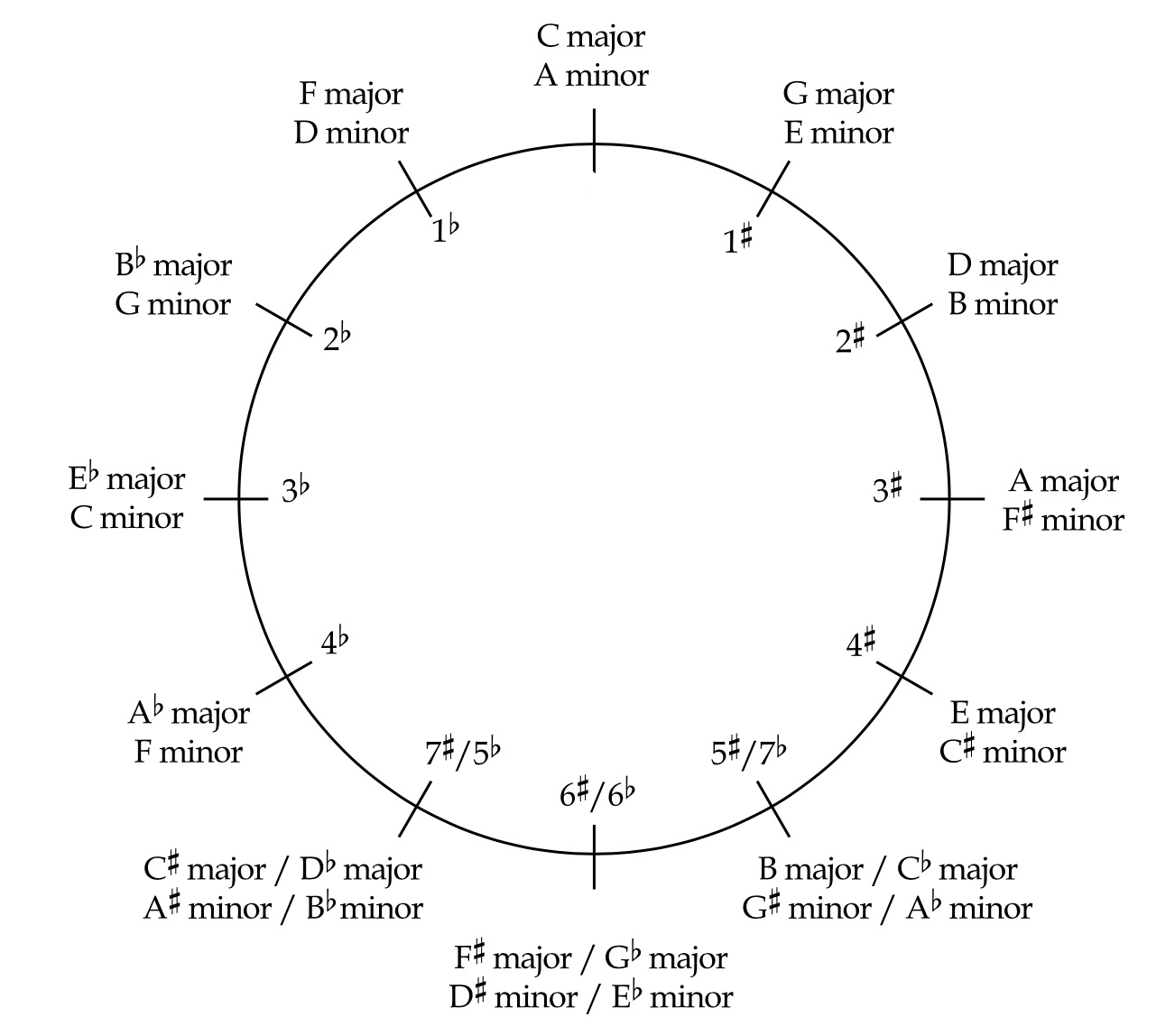

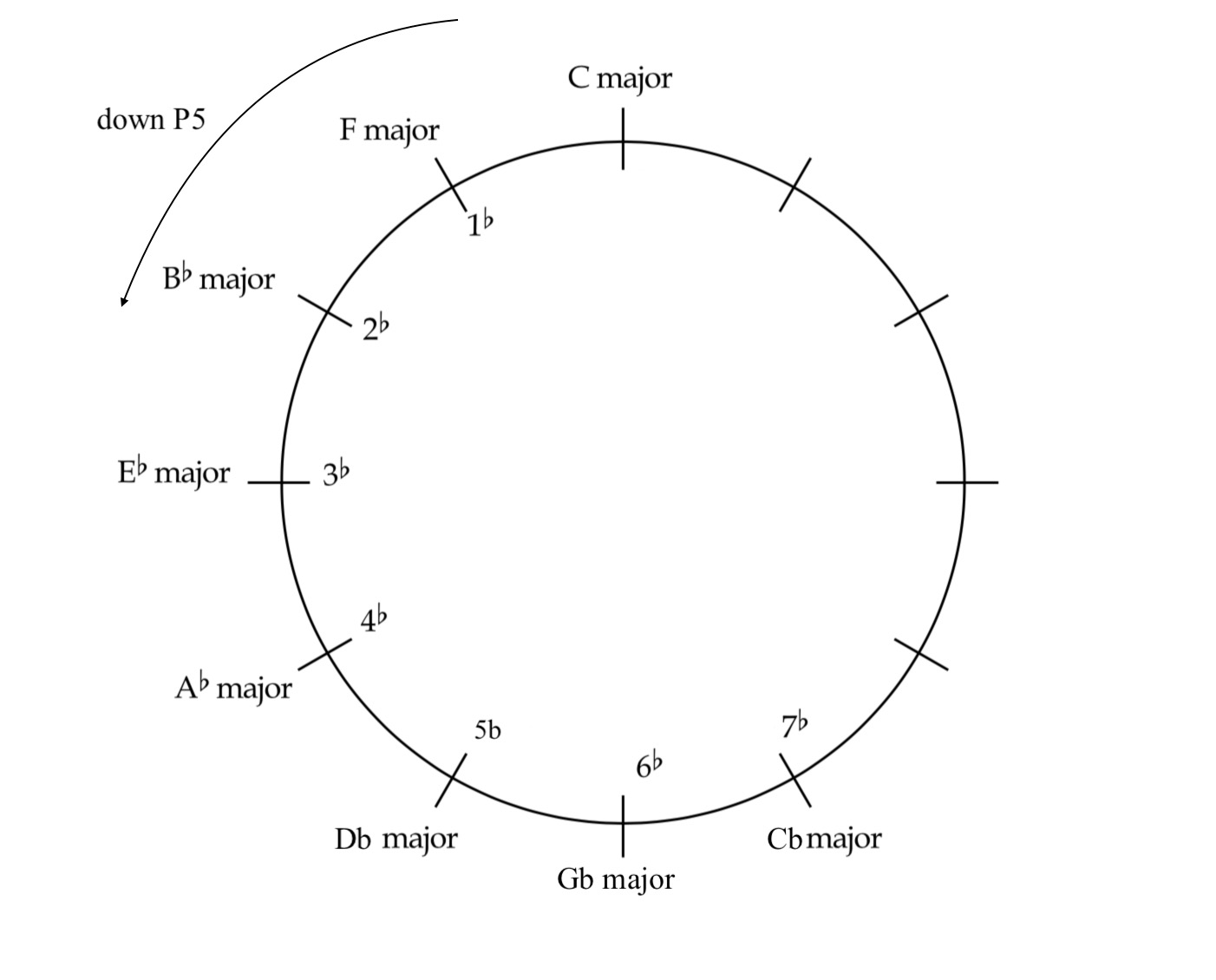

We can express this important pattern as a circle: the famous circle of fifths that you see in a simplified version at the top of this article, and in plain black and white below.

For now, just think about the progression of sharps and flats as you move from key to key in intervals of a 5th. Memorize the key signatures for each scale.

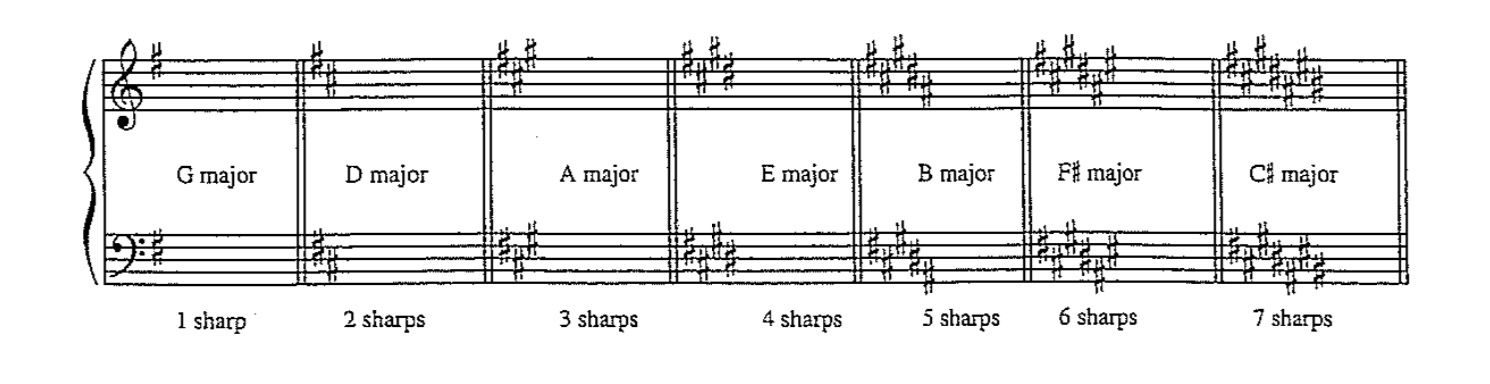

As mentioned in the video, we can continue with the scales with six sharps (F♯ major) and seven sharps (C♯ major). Notice that there is a pattern: each time we go up a Perfect 5th (or P5) and build a major scale, one new sharp needs to be added. And that new sharp always falls on scale degree 7 (the leading tone) of the scale, which is a half-step below the tonic.

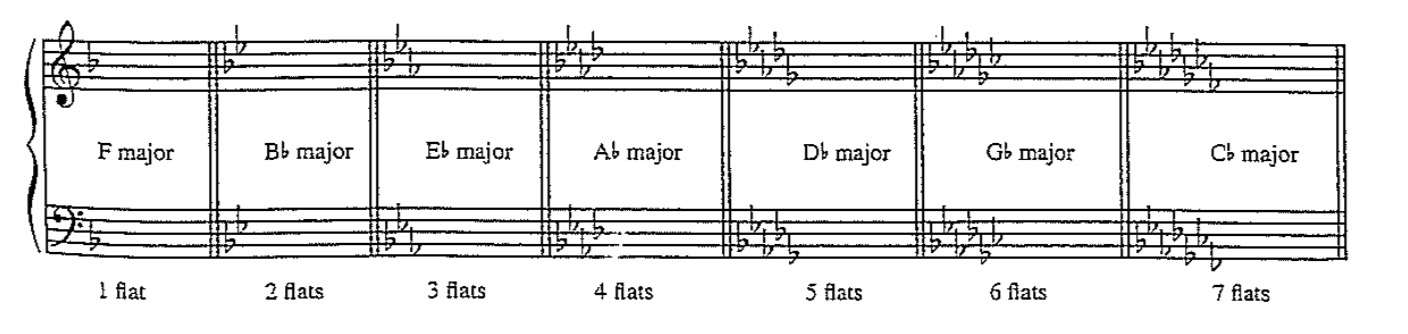

When writing music in a key that contains sharps or flats, it is convenient to use a key signature. A key signature is a collection of all sharps or flats necessary in a given scale, and it appears at the beginning of each staff right after the clef. The key signatures can contain up to seven sharps and seven flats, respectively.

Here are the key signatures, showing an increasing number of sharps. The key signature with seven sharps indicates that all seven notes in the scale carry a sharp, so it is for the key of C♯ major or its relative minor, A♯ minor.

It is very important to remember the order of the seven sharps: F C G D A E B. Notice that they go up a P5 from one to the next. Knowing the exact placement of the sharps on the staff is also important, especially the position of the fifth sharp, A♯, on both clefs. Practice writing them by hand, thinking about the name of the major scale for each key signature.

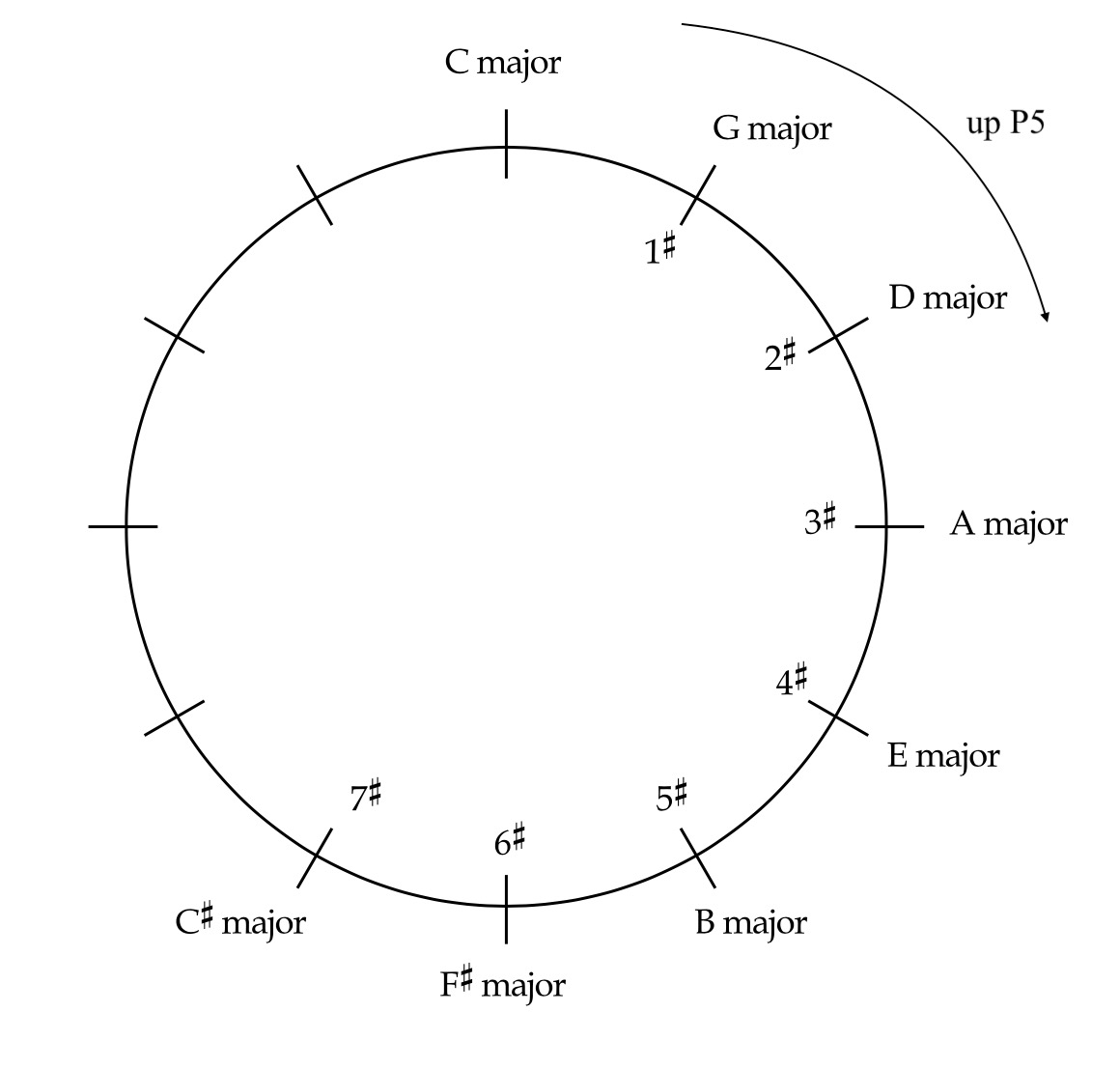

When we look at the circle of fifths, you’ll see that each letter represents a key. The circle looks like a clock, with 12 notches. If you go in the clockwise direction, each key is a P5 higher than the previous one, and the number of sharps increases for each ascending P5. Here is a portion of the circle showing the keys with sharps.

Here you can see these keys on the piano keyboard, ascending by P5 from C up to C♯. Play these notes on your keyboard, thinking about the number of sharps for each key.

DOWNLOAD A FREE MUSIC THEORY HANDBOOK

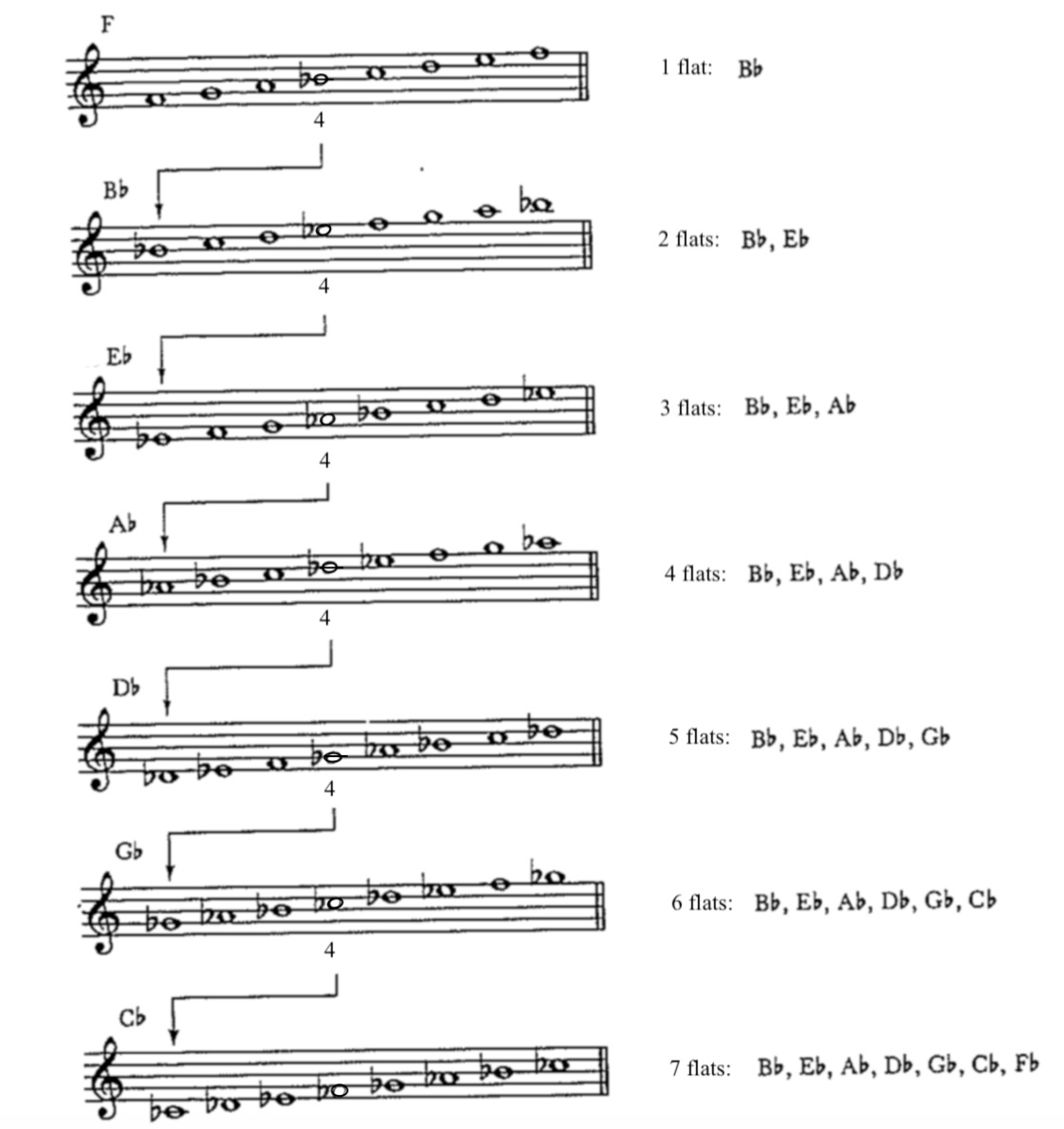

Now we can try constructing major scales in the opposite direction by successively going down a P5, starting from C major. Notice that going down a P5 is equivalent to going up a P4. We are duplicating the same pattern: W W H W W W H. In this instance, W represents a whole step, and H represents a half step.

- Go down a P5 from C to F, and construct the F major scale; it needs one flat: B♭.

- Go down a P5 from F to B♭, and construct the B♭ major scale; it needs two flats: B♭, E♭.

- Go down a P5 from B♭ to E♭, and construct the E♭ major scale; it needs three flats: B♭, E♭, A♭.

- Go down a P5 from E♭ to A♭, and construct the A♭ major scale; it needs four flats: B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭.

- Go down a P5 from A♭ to D♭, and construct the D♭ major scale; it needs five flats: Bb, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭.

We can continue with the scales with six flats (G♭ major) and seven flats (C♭ major). Notice that there is a pattern: each time we go down a P5 and build a major scale, one new flat needs to be added.

Here are the key signatures, showing an increasing number of flats. The key signature with seven flats indicates that all seven notes in the scale carry a flat, so it is for the key of C♭ major or its relative minor, A♭ minor.

It is very important to remember the order of the seven flats: B E A D G C F. Notice that they go down a P5 from one to the next; interestingly, it is the reverse order of the sharps. Knowing the exact placement of the flats on the staff is also important, so please practice writing them by hand, thinking about the name of the major scale for each key signature.

On the circle of fifths, the order of keys with flats follows the counterclockwise direction. Each key is a P5 lower than the previous one, and the number of flats increases for each descending P5. The following is a portion of the circle showing the keys with flats.

Here you can see these keys on the piano keyboard, descending by P5 from C down to C♭. Play these notes on a keyboard, thinking about the number of flats for each key.

Here again is the complete circle with all major keys and their respective relative minor keys. Please note that the major and minor keys in relative relationship share the same key signature.

You might wonder why the circle shows 15 major keys, although there are only 12 pitches in an octave. It is because there are three pairs of enharmonic keys that contain five, six, and seven sharps or flats. You can also look at it this way: seven keys with sharps, seven keys with flats, plus C major.

Here is a summary.

- Scales built on each successive P5 in the clockwise direction will require an additional sharp.

- Scales built on each successive P5 in the counterclockwise direction will require an additional flat.

If you’re feeling confident about your memorization of the circle of fifths, here is a helpful workshop from MusicTheory.net to help you identify major keys. Try it out and see how you do. If you don’t do as well as you want, just keep coming back to this lesson to practice.

It is essential that you review the scales by writing, singing, and playing them on a keyboard every day. Please be patient with yourself in the process. Internalizing music theory and integrating it with your ears will take time and consistent work. A thorough knowledge of scales and key signatures will help you become fluent with intervals and later with chords. As building blocks of chords, intervals (especially the 3rds and the 5ths) will provide the basis for understanding harmony, which we explore much more deeply in Music Application and Theory. Happy learning!