The following information is excerpted from the Berklee Online course Commercial Songwriting Techniques.

If I came to your house for Thanksgiving, I would undoubtedly compliment the chef, your Aunt Louise, on the delicious spread of creamed corn and stuffed turkey. Aunt Louise would probably smile and generously offer me another helping. But, if I wanted to sincerely thank my host for the outstanding meal, I would be more specific. I would mention how crisp and fresh the buttery corn tasted as the tiny kernels burst between my teeth, and how the golden brown crust on the glistening turkey sealed in all the juices. That would not only get me another helping; it might also convince Aunt Louise that my flattery was sincere.

Now, my point is not to make you hungry; my point is to display how specific detail has the ability to intensify an experience. Detail allows your audience to step into your shoes, know what you know, and feel how you feel. No doubt, Aunt Louise would have appreciated my keen attention to her cooking. She would have believed I was telling the truth and not just making sure I’d be asked back next year.

Effective songs paint rich images for the listener. Imagine that your songs are paintings. Are you the proud creator of stick figures scrawled across construction paper, or does your palette of texture, color, and light capture the desires and deepest wanderings of those gazing upon it?

Destination Writing

To make sure that the answer to that question is the latter, we’ll use a writing process called destination writing. In destination writing, you begin with one key word—a place—as the momentum for your song content. You may be familiar with a similar writing technique, called object writing, in which you use your senses to expound creatively on a topic. (For more information on object writing, refer to Writing Better Lyrics by Pat Pattison, Writer’s Digest Books, 1995.)

The key to utilizing these songwriting techniques for both destination writing and object writing is to use all of your senses as springboards for creativity. When those senses are involved, the writing springs to life.

- touch

- taste

- sight

- smell

- sound

- movement

The difference between object writing and destination writing is your starting point: your keyword. For destination writing, we’ll write from a place, a person, or a time, instead of an object. This way we not only practice the specific detailed writing needed to draw our audience in; we also discover phrases and topics that become the central ideas of our song lyrics. Destination writings need not be perfect. Do NOT edit your paragraphs.

Below are two paragraphs written about the same place, “motel room.” The first lies flat, while the second actually intensifies the experience of being in that motel room, making you feel part of the story.

Destination Writing 1: Motel Room

I put my card in the slot and the light turned green. As I opened the door, cold air came out. With my luggage behind me, I walked into the old-smelling room. It had a small kitchen and drapes, and I could still smell the food from past guests. The hallway had the same smell. The air didn’t move out there, either.

Destination Writing 2: Motel Room

I swiped my card and waited for the little light to turn green. The door stuck slightly and exhaled as I unsealed the vacuum and rolled my luggage behind me into the room. It smelled musty and old, even though I could still smell the nauseating scent of lemon cleaner that had been used to disinfect the bathroom. Nursing homes have that same smell, mixed with the tang of perm solution and instant coffee. I thought about how much I missed you, how this would all be bearable if you were here. But you’re not. The sour smell made the hairs in my nose curl. I felt the cold rush of air-conditioned air that had undoubtedly been cranked on high to dispel the mold in the carpet and the smell of grease that flecked the draperies from the residents who had cooked there before me. Those were the same smells I caught rolling down the hall, breathing in the stale air that hung in the hallways from lack of ventilation and the owner refusing to spend money on heating and cooling these transitional areas . . .

By involving all the senses, the event becomes an experience. The effectiveness of that experience is not contained within the idea itself, but in the way that the details connect with the reader’s emotions.

At this point you may be thinking, “These songwriting techniques sound good, but I just can’t write like that.” Well, I’m going to let you in on a secret. Ready? You can. The answer lies in your use of tiny powerhouse words called verbs and adjectives. Very simply, verbs describe movement. Driving, hopping, thundering; those are all ways in which a person or an object could move. Adjectives describe the characteristics of a person or object. Wicker chair, tattered quilt, hopeful eyes; these words give personality to everyday nouns. Those powerhouse words mean the difference between a bored audience and one that is hanging on your every word.

Walk: wander, stroll, march, step, strut, shuffle

Put: lay, set, store, place, plant, fix

Say: utter, breathe, blurt, pronounce, stammer, stutter, mouth, jabber, muffle

Shine: glint, glare, sparkle, radiate, shimmer, flash, blaze, beam, flicker

Realize: discover, find, determine, unravel, interpret, unearth, disclose, recognize

PRACTICE

Practice these songwriting techniques by using your senses to describe the destination: a “bus station.” Answer the questions below in as much detail as possible.

- What are you standing or sitting on?

- What do you smell?

- What do you taste?

- What around you is moving?

- What do you hear?

- What clothes, jewelry, and hairdo are you wearing?

- What are you feeling?

Look over your descriptions from the exercise. Compare your verbs, nouns, and adjectives with those listed below. If you find duplicates, you may not be getting specific enough. Try replacing those generic placeholders with some alternates and compare the results. Also, locate any nouns standing alone without the help of descriptive adjectives and give them a friend.

Examples of Generics: good, bad, food, walking, sitting, sad, smell, taste, hear, big, small, pants, shoes, shirt, dress, earrings, necklace, suit and tie, smile

External and Internal Detail

Your highly compelling destination writing will consist of two types of detail: external and internal. External details are words and phrases that describe what is going on around your main character. Internal details are words and phrases that describe what is going on within the heart and mind of your character. These two kinds of detail have another characteristic as well. External details evoke a concrete image. Internal details do not.

If I told you that “I feel so bad now that he’s gone,” you might be mildly concerned. But if I told you how I felt by saying, “My eyes are red and swollen from salty tears sliding down my cheeks now that he’s gone,” you’d be more attentive. By using external detail describing taste, sight, and movement, I intensify the experience. You picture my tears, my swollen eyes, and the salty streaks on my cheek. Just telling you that I feel bad isn’t enough. You’ve got to feel it yourself.

External Detail

- actions and objects surrounding the main character

- concrete

- provokes an image

Internal Detail

- thoughts and emotions within the main character

- abstract

- does not provoke an image

- often metaphorical

PRACTICE

Are the following phrases internal or external? Try asking yourself these questions:

- Does the phrase describe what’s going on around the main character? If yes, then the detail is external.

- Does the phrase describe what’s going on within the heart or mind of the main character? If yes, then the detail is internal.

Consider me gone.

internal

Crisp, brittle oak leaves

external

I thought it was love.

internal

Coarsely woven tattered quilt

external

Thin black eraser crumbs

external

There’s no one else like you.

internal

Now that you can tell external detail from internal detail, you are ready to organize those details into pre-song form. One of the exciting results of implementing these songwriting techniques and laying your ideas out this way is the ease with which you can recombine them into masterfully written sections. Mastering your destination writing technique will allow you to be flexible about the words you choose, while still retaining your unique perspective as an artist.

To organize your ideas, you’ll first underline the external words and phrases. Underline only the essence of the phrase: mainly verbs, adjectives, and nouns.

Right

in the cold, dank air

Wrong

in the cold, dank airYour phrases will seldom be longer than a few words. Watch for phrases that can be broken up into two smaller phrases. Omit conjunctions and prepositions like: at, in, by, into, on, until, with, as, so, only, even. Retain only the skeleton of the idea.

Right

dew-covered lightly frosted grassWrong

dew-covered, lightly frosted grassAfter you have underlined the external details, it’s time to identify the internal details. Draw parentheses around any word or phrase that details thought and emotion. For internal detail, you’ll often find it difficult to omit any part of the sentence or phrase. That is because it is a thought or feeling, and each word plays an integral part in the meaning. Do your best to include the smallest portion of the phrase, while still retaining the meaning of the phrase.

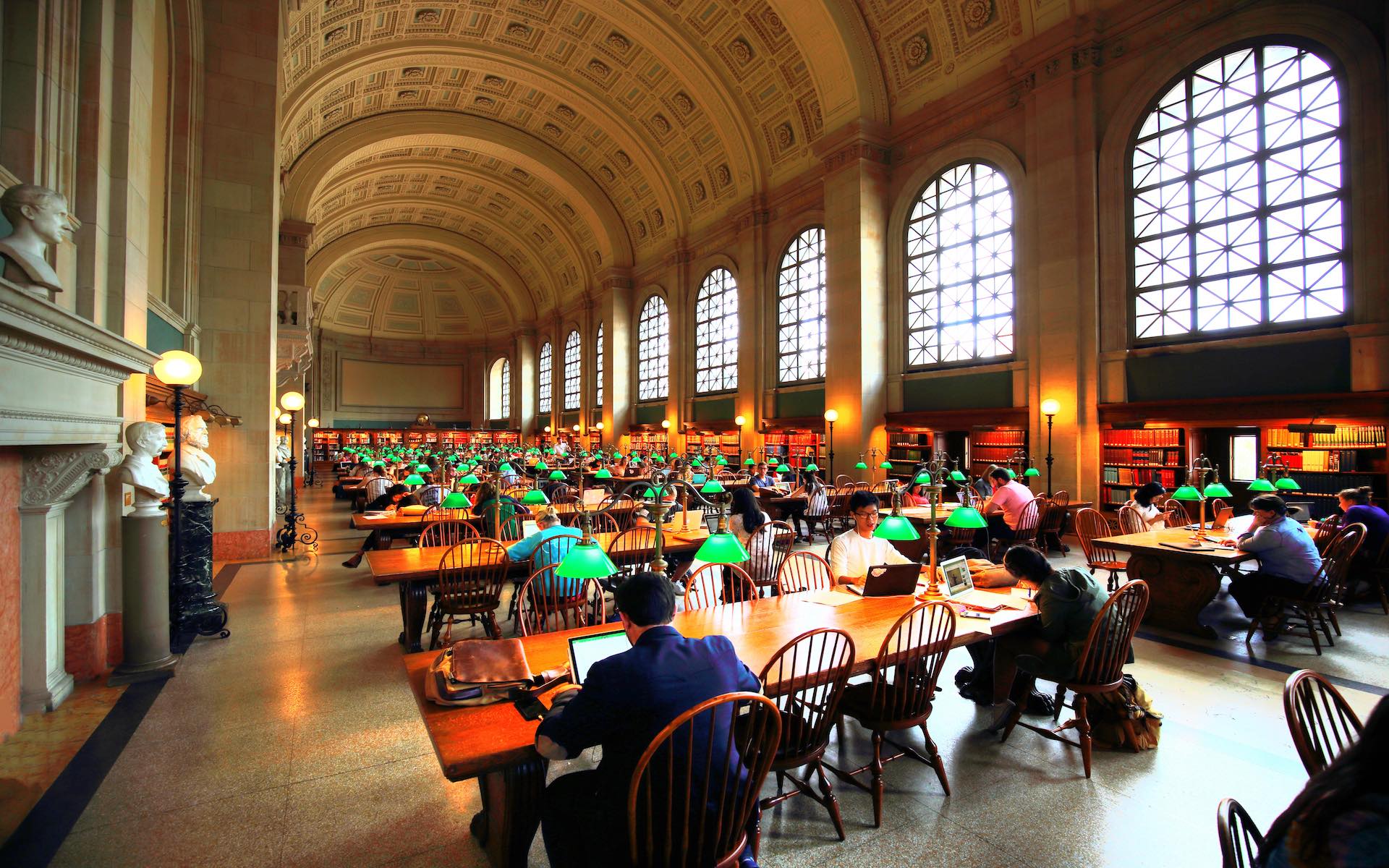

Example using the word “library”:

The long oak table, sturdy and lit with three small study lights seemed to absorb all sounds that might have come from the aisle of books and studying students. Swung my backpack around and let it sag against the leg of the chair furthest on the left, next to the drinking fountain. I felt my low rider jeans sneak further down as I twisted my body under the table looking for a place to plug in my laptop. (All eyes might have been looking at me). (I didn’t care). The zipper of my bag caught in the frayed fibers of the seams, overstretched and worn from two years of thick history books and stacks of research.TRY IT

Set a timer for six minutes and destination-write using the topic “coffee shop.” Once you’re finished, underline the external and internal phrases from your piece and divide them into two lists. This becomes your “word library” for the song you are writing.

STUDY MORE SONGWRITING TECHNIQUES AT BERKLEE ONLINE