Mastering Smooth Chord Transitions on Guitar with Drop-2 and Functional Harmony

The following information on voice leading for guitar is excerpted from Chapter 1 of the Berklee Press book Voice Leading for Guitar: Moving Through the Changes, authored by John Thomas.

Harmony Review

Chord Types: Diatonic Seventh Chords

In jazz, you will encounter only seven kinds of diatonic seventh chords (from major, melodic minor, or harmonic minor keys). This article will show you how to voice lead smoothly and easily between these chords and their variations. The simplest forms of these chord types appear below.

Fig. 1. Diatonic seventh chords in the key of C

Note: Major 6 chords fulfill the same function as major 7 chords.

Sometimes minor 6 chords can fulfill the same function as minor 7 chords.

Harmony and Progressions

In order to move smoothly from chord to chord–to voice lead–you must know the rules that govern the behavior and relationship of individual notes and groups of notes (chords) in a chord progression.

Chords and chord progressions help to establish tonal areas. In Western music, there are three tonal areas: tonic (T), subdominant (SD), and dominant (D). Each area is associated with a scale degree and the chord built upon that scale degree. Nearly every type of composition, from the simplest folk song to a Beethoven symphony, is based on movement between these tonal areas.

Fig. 2. Diatonic seventh chords and function in the key of C

Chord Functions

Each chord has a distinct function within a chord progression, depending on its tonal area. The chord’s function determines its tendency to establish either motion or stability within a musical phrase, a song, or a larger composition. Chords that have similar function can substitute for each other.

Tonic

In a major key, the tonic area includes chords built upon scale degrees 1, 3, and 6. In major, IMaj7 is the defining sound of the tonic area. In melodic and harmonic minor, I–(Maj7) is the defining sound. Tonic chords have a resting or stable function. Tonic-area seventh chords can substitute for each other because they all share three common tones and have the same harmonic function.

Subdominant

The subdominant area includes seventh chords built upon scale degrees 2, 4, and 6. Chords built on scale degree 4 are the defining sound of the subdominant area. Subdominant chords impart a moderate sense of forward motion in a progression. In major, both II–7 and VI–7 can be substituted for IVMaj7 because they share several common tones and the same harmonic function. In melodic minor and Dorian, IV7 can be replaced by II–7 or VI–7(♭5). In harmonic minor, IV–7 can be substituted by II–7(♭5) or♭VIMaj7.

Dominant

The dominant area includes chords built on scale degrees 5 and 7. The V7 chord is the defining sound of the dominant area. Dominant chords tend to sound unresolved because of the tritone interval between chord tones 3 and 7. They impart a strong sense of forward motion in a progression. Although less common, the VII–7(♭5) chord can be substituted for V7 in major and melodic minor, because the two chords share the same tritone and have the same harmonic function. In harmonic minor, VII°7 can replace V7.

Secondary Dominant

Every major key, melodic minor key, and harmonic minor key has a dominant. Additionally, every chord has its own dominant, which is the seventh chord located a fifth above it. It is referred to as a secondary dominant. (The only exception to this rule is the diminished chord, which has no dominant.) Secondary dominants can help smooth out voice leading between chords and add new dimension and color to every key by introducing notes that are not in the key.

Voice Leading in Action: Simple Chord Families on the Guitar Neck

The term “voice leading” refers to the way in which individual voices move from chord to chord. The best voice leading occurs when all individual voices move smoothly. You can achieve this by moving between chords using the same note or moving up or down by a step in the inner voices of the chord, whenever possible.

Read and play through this simple voiceleading exercise. Chords are voice led so that only one voice moves at a time. Note how the stepwise motion between the chords illustrates how closely the chords are related. These chord families form the backbone of comping using standard four-part harmony.

Practice this exercise chromatically, in all twelve keys.

Fig. 3. Simple chord families

Voice Leading Chord Tones and Tensions

In the classical voice leading tradition, there are strict rules that govern how individual chord tones and tensions should move in a harmonic progression. Functional jazz harmony also follows these rules. In general, voice leading favors conservation of motion: chord progressions sound smoothest when each note in a chord moves in stepwise motion, or in short leaps of no more than a major third, to corresponding chord tones or tensions in the next chord.

Voice Leading Chord Tones

In a II–7/V7/I progression, for example, the seventh of the II–7 chord must resolve to the third of the V7 chord. Additionally, the third of the II–7 chord must resolve to the seventh of the V7 chord.

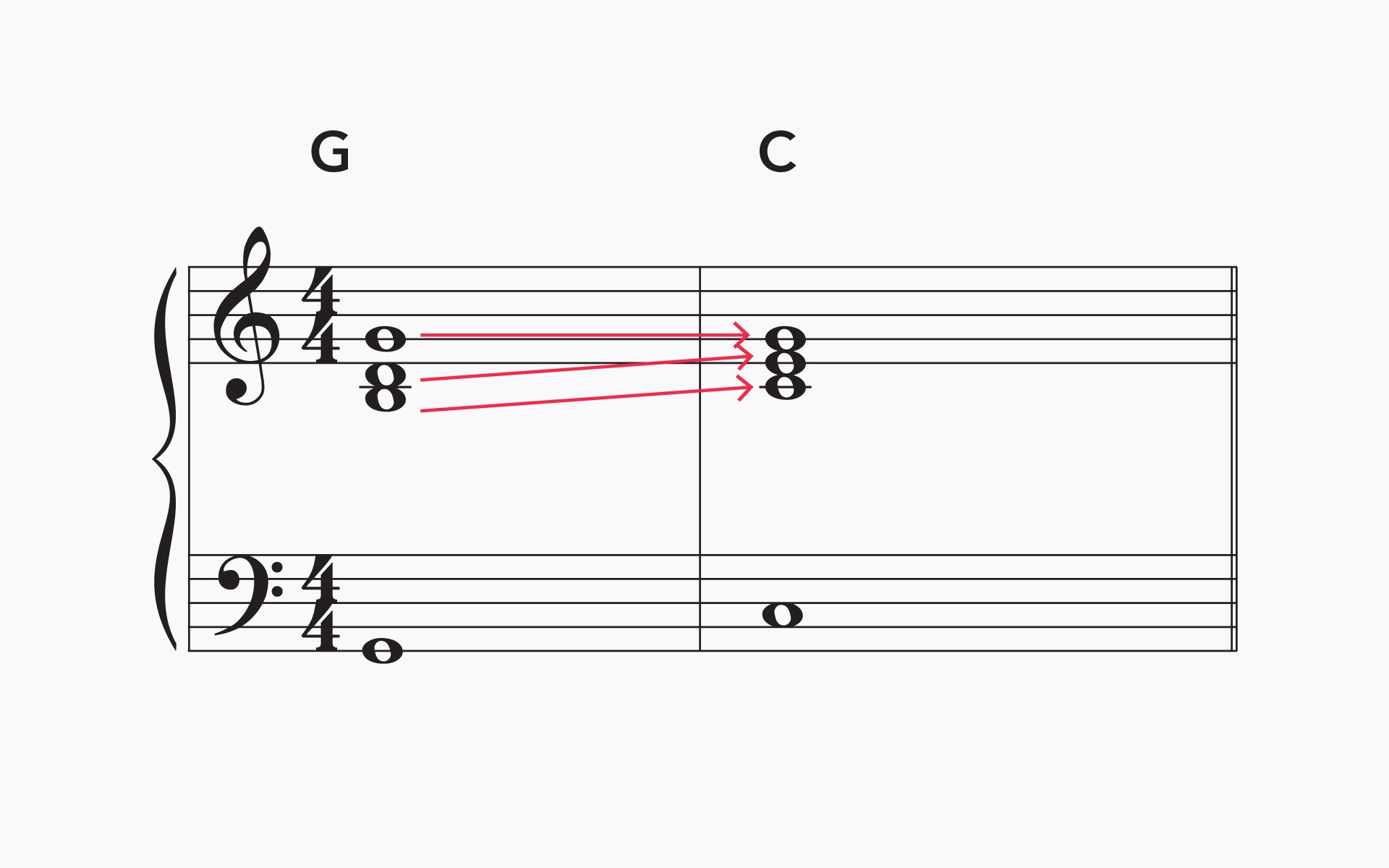

Fig. 4. Resolution of chord tones 3 and 7 in a II–7/V7 progression

When moving from V7 to I (major or minor) the seventh of the V7 chord resolves into the third of the I chord. Conversely, the third of the V7 chord resolves to the seventh of the I chord.

Fig. 5. Resolution of chord tones 3 and 7 in a V7/I progression

There is an important exception to the rule. When the third or the seventh in either of the first two chords in a II–7/V7/I is doubled, only one of the doubled notes resolves to the target note (the third or the seventh of the chord).

In the following example, the third of D–7 is doubled. The first F does not move, and becomes the seventh of G7. The other F resolves downward to E, which is the thirteenth of G7.

Fig. 6. Resolutions with doubled thirds

In fig. 7, the D–7 spelled D, A, C, F, C would resolve to a G7 spelled G, D, F, B. You will notice that in the first chord, the seventh (C) is doubled. The upper C resolves to the third of G7, which is B. The lower C in D–7, however, moves up a whole step to D, the fifth of G7.

Fig. 8. Resolutions with doubled thirds and sevenths

Fig. 9. Resolutions with doubled sevenths

These are not the only possibilities. The two examples below illustrate how doubled thirds resolve to doubled sevenths, and how doubled sevenths resolve to doubled thirds.

Voice Leading Chord Tensions

As illustrated in fig. 3, jazz musicians will almost always add color to the basic chords by using tensions—ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths placed above the basic seventh chord. Tensions are nonessential notes used to add color to a chord. These tensions are rarely indicated in most jazz charts, however. Each musician chooses which tensions to use, based on the musical context.

Tensions, like chord tones, have very specific behaviors, as indicated in the following musical examples. The resolutions in the examples below are common in II–7/V7/I progressions.

Whether a 13 goes to a 9 or♭9 depends on the construction of the scale that the chord is built on. These scales are called chord scales. Some chord scales have♭9 instead of 9, or♭13 instead of 13, and so on. (Refer to the appendix for a discussion of chord scales and modes.) Note the resolutions of 9 and 13 in the chord progression below.

Fig. 16. Resolutions of 13 and 9 vary according to chord scale.

Finding the Correct Chord Scale: A Guide

Choose tensions carefully. The quality of the tensions you choose must correspond to the appropriate chord scales and must be compatible with the chord’s harmonic function. Below is a list of chords and their corresponding chord scales and modes. (Refer to the appendix for more information on chord scales and modes.)

This chart covers only the scales used most often in traditional functional harmony and improvisation in jazz. However, you’ll find many other scales being used extensively in modern tunes, such as modal music composed by Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, and other contemporary musicians.

Other Smooth Moves: Parallel Movement

When a chord moves to another whose root is only a second or third away, all voices must move up or down stepwise or in thirds, respectively, to corresponding notes in the second chord: root moves to root, third to third, fifth to fifth, and so on. This is called parallel movement. It is a common means of leading voices and is the easiest one for a guitarist to perform–however, it can only be used when chords move stepwise or in thirds. (You’ll see examples of parallel movement in “I Should Have Thought About Me” and in bars 5–6 of “I Smell Catastrophe,” both in chapter IV.)

For instance, in measure 1 of the example below, chords move from CMaj7 spelled C, B, E, G to D–7 in the key of C. D–7 is spelled D, C, F, A. Note that all notes in D–7 are located a (diatonic) second above those of CMaj7.

Accordingly, if you had to move from CMaj7 spelled C, B, E, G to E–7, you might spell E–7 in this way: E, D, G, B.

To summarize, thirds go to thirds, fifths to fifths or thirteenths, sevenths to sevenths, and tonics to tonics or ninths. To those of you who have already been initiated into the world of traditional harmony, this might sound like heresy. For us jazzers, however, it is the Holy Grail.

Fig. 17. Chord resolutions

Drop-2 Voicings

The chord voicings you use can make an enormous difference in the quality of your voice leading. One of the most helpful voicings is the drop-2 voicing. Drop-2 voicings are chords played in close position, in which the alto (middle) voice is played one octave lower than the original alto, in close position.

This lays well on the guitar fretboard and makes voice leading from one chord to the next easier. Drop-2 voicings are everywhere in jazz guitar voice leading.

Fig. 18. Close and drop-2 chord voicings

STUDY GUITAR ONLINE WITH BERKLEE